The Federal Reserve helped rescue the economy from the worst pandemic in a century. That task may prove easy compared with the Fed’s next mission: crush inflation, without causing a recession.

Achieving a so-called “soft landing” will be challenging because the jobs market is on fire. It’s so hot that the unemployment rate may need to rise to get inflation under control.

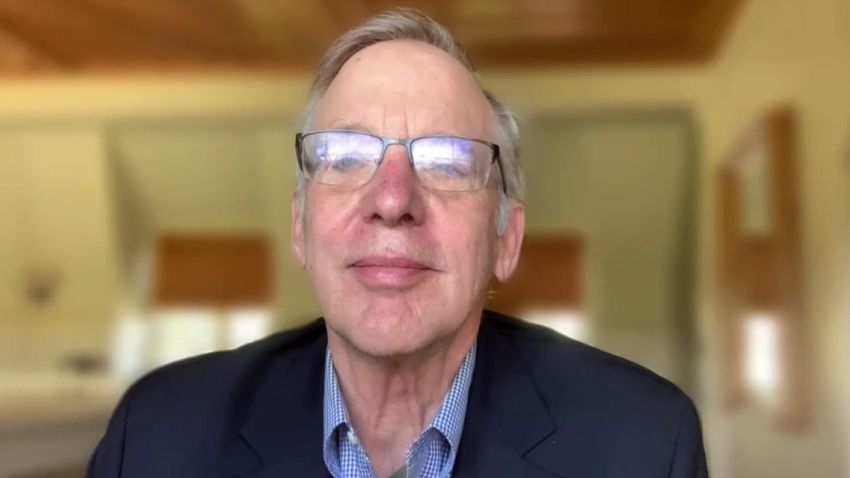

“The chances of pulling this off are very, very low because they have to push up the unemployment rate,” Bill Dudley, the former president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, told CNN.

History is not on the Fed’s side.

“In the past, when you’ve pushed up the unemployment rate, you’ve almost never been able to avoid a full-fledged recession,” Dudley said. “The problem the Fed faces is they’re just late.”

Technically, the Fed has the ability to catch up to inflation — by raising interest rates rapidly.

The US central bank is widely expected to announce on Wednesday its first interest rate hike of half a percentage point since 2000. Markets are bracing for a series of large rate hikes to cool off the worst inflation in 40 years.

In theory, the US central bank can raise interest rates as high as needed to put the inflation fire out. But the more the Fed does that, the greater the risk of a miscalculation that prematurely ends the recovery.

“That’s why soft landings are so difficult to pull off,” said Dudley, who led the New York Fed from 2009 until mid-2018. “By the time you know you’ve overdone it, the next thing you know, you’re already in a recession.”

‘Very difficult assignment’

Current Fed officials and some economists express cautious optimism about avoiding a feared hard landing for the economy. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell has pointed to soft landings that occurred in 1965, 1984 and 1994.

“I believe that the historical record provides some grounds for optimism: Soft, or at least soft-ish, landings have been relatively common,” Powell said in a March speech.

However, Dudley notes that in those examples, the unemployment rate didn’t actually increase.

Today, the unemployment rate stands at just 3.6%, well within the range the Fed considers full employment. And the jobless rate is likely to keep dipping, perhaps hitting levels unseen since the early 1950s.

“The Federal Reserve has to slow the economy down and generate some slack in the labor market,” Dudley said. “That’s a very difficult assignment to pull off.”

The former Fed official says history shows that when the unemployment rate starts to rise, it typically “provokes a full-blown recession.”

That may be for psychological reasons. “People, once they start to see the job market is deteriorating, they start to get worried about their own job prospects. You pull back on consumption and spending,” Dudley said.

Low recession risks for now?

The good news is that a recession does not appear imminent. And Goldman Sachs, Dudley’s former employer, has been telling clients that a recession is not inevitable.

Still, worries about the economy were reinforced by last week’s gross domestic product report, which showed the US economy unexpectedly contracted during the first quarter.

Many economists say the surprise GDP report reflects temporary factors that overshadowed strong consumer and business spending.

Dudley said GDP went negative because of “some crazy stuff” related to inventories and trade, adding that the underlying demand in the economy is “strong.”

“There is very little chance of recession in the next year,” Dudley said.

Higher than 50% chance of recession in 2023 and 2024

The concern is how the US economy in 2023 and 2024 withstands a series of interest rate hikes that will jack up the cost of mortgages, car loans, credit cards and business loans.

Once the Fed brings interest rates above the neutral level, it will effectively be slamming the brakes on the economy. That’s when the risk of a recession “goes up a lot,” Dudley said, adding that the chance of a recession in 2023 and 2024 is “definitely higher than 50%.”

Of course, the Fed could decide to stop raising interest rates if it fears setting off a downturn.

In some ways that’s what happened in 2019, when the Powell-led Fed halted rate hikes amid slowdown fears. No one knows how that would have turned out because Covid-19 hit in early 2020, forcing the Fed to dramatically slash interest rates.

“The Fed could try to procrastinate,” Dudley said. “But if they do that, inflation will likely come back and then they’ll have to slam on the brakes even harder. Procrastination doesn’t really lead to a good outcome. That just leads to a harder landing down the road.”

‘Policy mistake’

Recession fears today — just two years into this economic recovery — underscore the difficult position in which the Fed finds itself.

Last spring and summer, the Fed shrugged high inflation off as “transitory,” a phrase it has since abandoned. The central bank opted to keep its emergency policies in place, hoping inflation would cool off.

Inflation has proven to be more persistent and broad-based than economists and investors anticipated, in part because of surprises including additional Covid-19 supply disruptions and now the war in Ukraine.

At the same time, the jobs market raced back to full employment faster than expected. Powell conceded in March that, with the benefit of hindsight, “obviously” it would have been appropriate for the Fed to have moved into inflation-fighting mode earlier.

Although Dudley says the Fed deserves “credit” for its “powerful and very fast” response to the pandemic in early 2020, he suggests it also deserves blame for its inflation response.

“They were very, very late in removing monetary policy accommodation,” Dudley said. “That’s going to turn out, in retrospect, to be a bit of a policy mistake.”