The Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, opened to great fanfare in November 2017. Among its most prized acquisitions featured at the opening were 16 purported fragments of the famous Dead Sea Scrolls. But in a blow to the fledgling museum, an independent scientific analysis has now revealed that all 16 of those fragments are modern forgeries. While the identity of the forgers remains unknown, it seems all 16 came from the same source, although they were purchased from four different sellers. The full report from Art Fraud Insights is available here.

"After an exhaustive review of all the imaging and scientific analysis results, it is evident that none of the textual fragments in Museum of the Bible's Dead Sea Scroll collection are authentic," Colette Loll, founder and director of Art Fraud Insights, wrote in the final report. "Moreover, each exhibits characteristics that suggest they are deliberate forgeries created in the 20th century with the intent to mimic authentic Dead Sea Scroll fragments."

"We're victims," museum CEO Harry Hargrove told National Geographic. "We're victims of misrepresentation, we're victims of fraud."

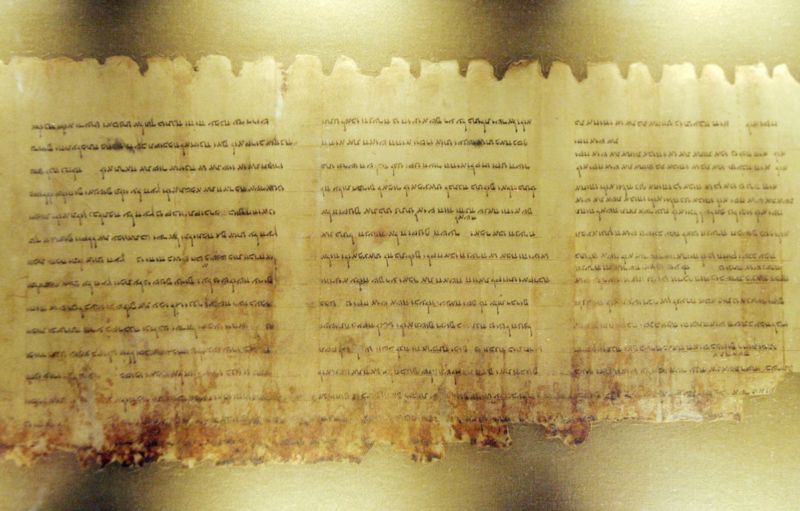

These ancient Hebrew texts—roughly 900 full and partial scrolls in all, stored in clay jars—were first discovered scattered in various caves near what was once the settlement of Qumran, just north of the Dead Sea, by Bedouin shepherds in 1946-1947. Qumran was destroyed by the Romans, circa 73 CE, and historians believe the scrolls were hidden in the caves by a sect called the Essenes to protect them from being destroyed. The natural limestone and conditions within the caves helped preserve the scrolls for millennia; they date back to between the third century BC and the first century CE. Almost all of the authentic Dead Sea Scrolls are housed in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

The $400 million nonprofit Museum of the Bible was founded by evangelical Christian billionaire Steve Green, president of Hobby Lobby, a chain of craft stores. This isn't the first time the museum has been faced with a fraudulent artifact in its collection. In 2019, the museum had to replace a miniature Bible on display, purported to be one of several carried to the moon on a 1971 NASA space mission. Author Carol Mersch, who received 10 so-called "lunar Bibles" from then-NASA chaplain John Stout, had doubts about its authenticity based on the engraved serial number. (There were only three digits, compared to five digits in the serial numbers for authentic Bibles.) Mersch donated a replacement lunar Bible to the museum.

Questions have been raised about the museum's Dead Sea Scroll fragments since at least 2016, when scholars noted inconsistencies in the inscribed writing when compared to authentic Dead Sea Scroll fragments, as well as certain suspicious physical anomalies. While the contested scroll fragments were on display at the museum's opening, the curators dutifully noted on exhibit labels that their authenticity had not been verified. In 2018, five of the fragments were tested by the Federal Institute for Materials Research in Germany and found to be forgeries, prompting the museum to hire Art Fraud Insights to analyze all 16 fragments in their collection.

Loll and her colleagues employed a comprehensive set of imaging techniques for their analysis and determined that all 16 were forgeries. Six fragments were then subjected to even more in-depth analysis under different wavelengths of light and high magnification, as well as materials analysis of the deposits on the fragment surfaces.

For instance, most of the authentic Dead Sea Scrolls are written on a hybrid of parchment and leather, usually based on the skins of cattle, sheep, or goats. Parchment is typically made from animal skins, with the hair and fatty residues removed via enzymatic or similar treatments in ancient times. Then the skins were scraped clean and stretched across a frame to dry.

-

Forged fragment of Genesis

-

Anomalies found in Genesis fragmentMuseum of Bible/Art Fraud Insights

But the Museum of the Bible's fragments are made of scraps of ancient leather rather than parchment, possibly remnants of old Roman-era shoes taken from archaeological digs. There are holes in many of the fragments that bear a striking resemblance to the lacing holes found in the remains of ancient shoes from a Roman excavation site in the UK, for example.

The leather had been coated with a shiny amber material, most likely glue made from animal skins. The ink used to write the script was of modern origin and had pooled on the old leather in a telltale fashion. The forgers also sprinkled the forgeries with clay mineral dust—similar in composition to that found in the Qumran Caves—after the inking in an attempt to cover up the fact that old leather had been used instead of parchment. So this is clearly a case of deliberate forgery.

There will no doubt be a fair amount of Schadenfreude in certain quarters over Green and his vanity project museum being taken in so thoroughly, especially given Hobby Lobby's controversial involvement with the purchase of more than 5,500 looted Iraqi artifacts. (The company lost a high-profile court case in 2017 and had to pay a hefty $3 million fine, in addition to returning the artifacts.) But the Museum of the Bible is hardly the first institution—and Green is hardly the first collector—to be taken in by such scams. Those 16 fragments were likely part of a much larger collection of Dead Sea Scroll forgeries that flooded the antiquities market around 2002.

It's to the museum's credit that its staff undertook a serious investigation to learn the truth and chose to be completely transparent about the findings. Despite the unfavorable results, Chief Curatorial Officer Jeffrey Kloha pointed out the scientific value of having done such an analysis on fragments that surfaced after 2002. "The sophisticated and costly methods employed to discover the truth about our collection could be used to shed light on other suspicious fragments and perhaps even be effective in uncovering who is responsible for these forgeries," he said.

reader comments

286