During the unrest in Iraq in April 2003, opportunistic looters stole some 15,000 priceless cultural artifacts from the National Museum of Iraq, taking advantage of the evacuation of museum staff until US forces were able to restore order. These artifacts have been showing up on the antiquities market ever since, often accompanied by forged or questionable claims of provenance. Thousands of them were purchased by Steve Green, CEO of Hobby Lobby craft chain store (and son of company founder David Green), on behalf of the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC. Those artifacts included the so-called "Dream of Gilgamesh" tablet, a rare cuneiform text dating back to ancient Mesopotamia.

US customs agents seized the tablet in 2019, and last week, a US District Court in New York ordered Hobby Lobby to forfeit the tablet so it could be returned to Iraq. An additional 17,000 looted artifacts are also being repatriated to Iraq, the result of a months-long effort between Iraqi authorities and the US. According to Iraqi Cultural Minister Hassan Nazim, "This is the largest return of antiquities to Iraq." Archaeological looting in Iraq has been going on for at least a century, with estimated revenues from the sale of stolen artifacts amounting to between $10 and $20 million annually.

“This forfeiture represents an important milestone on the path to returning this rare and ancient masterpiece of world literature to its country of origin,” said Jacquelyn M. Kasulis, acting US attorney for the Eastern District of New York. “This office is committed to combating the black-market sale of cultural property and the smuggling of looted artifacts.”

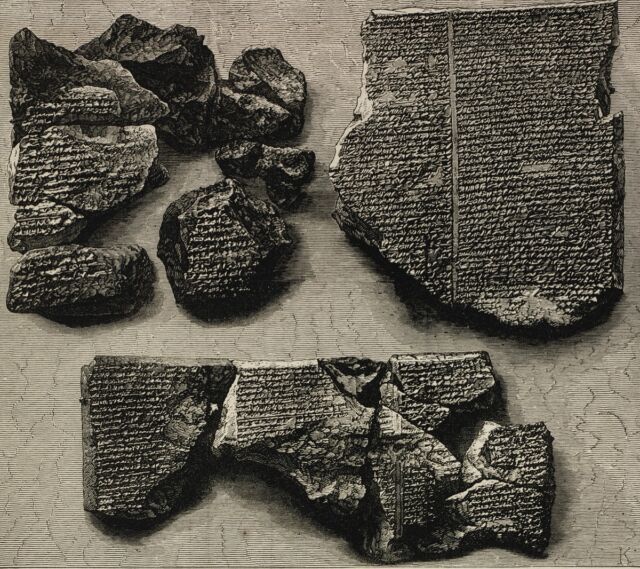

Gilgamesh is an ancient Mesopotamian epic poem. It's the earliest known surviving piece of literature and the second-oldest surviving religious text. Originally, there were five Sumerian poems telling the story of a king of Uruk named Bilgamesh (the Sumerian version of Gilgamesh). The poems date back to around 2100 BCE and provided the source material for the epic poem, told in the now-extinct Akkadian language. There are only a handful of surviving tablets of the Old Babylonian version, circa 1800s BCE. About two-thirds of a longer, 12-tablet version in Standard Babylonian survived, dating back sometime between the 13th and 10th centuries BCE.

The first part of the story centers on the unlikely friendship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu, a "wild man" created by the gods, purportedly to protect the people of Uruk from being oppressed by Gilgamesh. Before he meets the king, Enkidu succumbs to sexual temptation with a prostitute named Shamhat and hence becomes "civilized." When he arrives in Uruk, he challenges the king to a wrestling match.

Gilgamesh wins, but the two men become besties. They journey to the Cedar Forest with the aim of cutting down the sacred cedar tree. At some point, the goddess Ishtar tries to seduce Gilgamesh, who rejects her. Hell hath no fury, so Ishtar sends the Bull of Heaven down to punish them. When the BFFs slay the bull instead, the enraged gods execute Enkidu. The second part of the story follows a grief-stricken Gilgamesh on an ultimately fruitless quest to find the secret to eternal life.

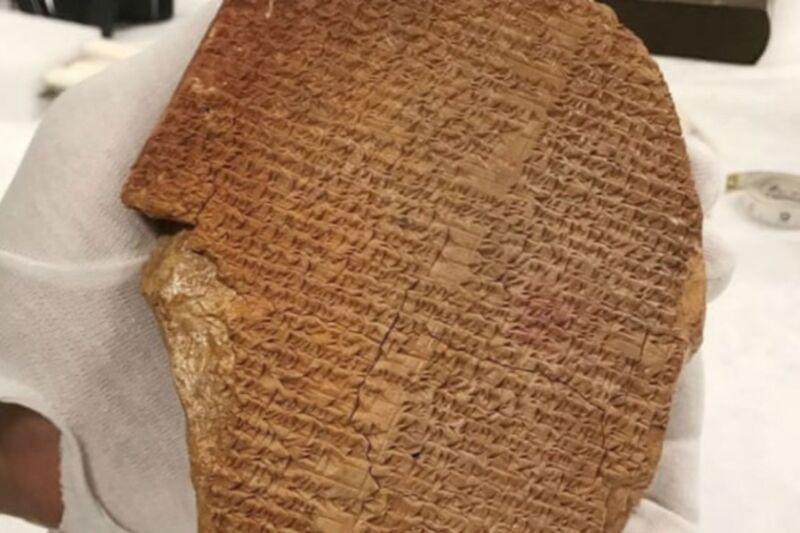

The "Dream of Gilgamesh" tablet concerns a section of the poem where Gilgamesh tells his mother about the strange dreams he's been having. According to the Department of Justice, an American antiquities dealer acquired the fragment in 2003 for around $50,000 from a relative of a coin dealer in London. Measuring just 6x5 inches, it was "encrusted with dirt and unreadable" when it was shipped to the US. Furthermore, the sender failed to declare the contents, thereby violating the law. Experts realized that it was a portion of the Gilgamesh epic after the tablet had been cleaned.

That same American antiquities dealer provided a false letter of provenance for the tablet when they sold it, claiming it had been found in a box filled with ancient bronze fragments, purchased at auction in 1981 from San Francisco's Butterfield & Butterfield auction house. The tablet changed hands a few more times before Steve Green bought it in a private sale from Christie's London auction house for $1.67 million in 2014.

Why would the Museum of the Bible be so keen to acquire one of the Gilgamesh tablets? Many of the poem's characters and story elements have strong parallels to stories in the Old Testament, suggesting that parts of the Hebrew Bible draw from the same source material. Most notably, the story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden is markedly similar to Enkidu's seduction by Shamhat, whereby he loses his pure "wild man" state.

At one point, Enkidu eats forbidden flowers, and the gods use one of his ribs to create Ninti, the goddess of life, to heal him. The Book of Genesis tells how God fashioned Eve out of Adam's rib to provide him with a companion, and Adam and Eve are banished from the garden after eating forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge. There's also a story about a great flood. Scholars are very confident both the Gilgamesh version and the story of Noah in Genesis drew from the same source material for their accounts. So the Gilgamesh tablet was certainly a desirable artifact to add to the Museum of the Bible's collection.

Green had been purchasing artifacts from the ancient Near East for the museum for years by the time he purchased the Gilgamesh tablet; the artifacts included a controversial 2009 shipment of clay bullae and tablets and another similar shipment in 2010. Museum staffers, as well as external antiquities experts, questioned the provenance of many of these artifacts, suspecting they may have been looted from Iraq. The accompanying paperwork was vague on details and lacked supporting evidence for the claimed history of ownership.

Eventually law enforcement took notice. US customs seized several Hobby Lobby shipments in 2011, culminating in a 2017 civil forfeiture lawsuit (United States of America v. Approximately Four Hundred Fifty Ancient Cuneiform Tablets and Approximately Three Thousand Ancient Clay Bullae). As part of the resulting settlement, the company was fined $3 million and required to forfeit over 5,550 artifacts that had been smuggled from Iraq.

The Museum of the Bible's reputation has also been marred by a number of fakes and forgeries in its collection. Among its most prized acquisitions were 16 purported fragments of the famous Dead Sea Scrolls. But as we reported last year, an independent scientific analysis revealed that all 16 of those fragments are modern forgeries. While the identity of the forgers remains unknown, it seems that all 16 came from the same source, although they were purchased from four different sellers. (The full report from Art Fraud Insights is available here.) "We're victims," museum CEO Harry Hargrove told National Geographic last year. "We're victims of misrepresentation, we're victims of fraud." And in 2019, the museum had to replace a miniature Bible on display, purported to be one of several carried to the Moon on a 1971 NASA space mission.

By March 2020, the museum had identified some 5,000 fragments of papyri and 6,500 clay objects from Egypt and Iraq in its collection that also had questionable provenance and vowed to return them. “My goal was always to protect, preserve, study, and share cultural property with the world," Green said in a statement at the time. "That goal has not changed, but after some early missteps, I made the decision many years ago that, moving forward, I would only acquire items with reliable, documented provenance. Furthermore, if I learn of other items in the collection for which another person or entity has a better claim, I will continue to do the right thing with those items.”

It looks like he's making good on that promise. Just this past January, Green announced that the museum had returned over 8,000 clay objects to the Iraq Museum, and the DOJ said that Hobby Lobby has consented to the forfeiture of the Gilgamesh tablet. Hobby Lobby, in turn, has filed lawsuits against Christie's for selling it the Gilgamesh tablet and against an Oxford University classics professor, Dirk Obbink, who allegedly sold the company stolen Bible fragments.

reader comments

224