Meta recently joined the ranks of tech giants calling for the end of the leap second, the fascinatingly complex way humans account for tiny changes in the Earth’s rotation timing. The owner of Facebook and Instagram adds to a chorus that has been growing for years, and the debate could come to a head at a global conference in 2023—or even sooner if the Earth keeps having record-short days.

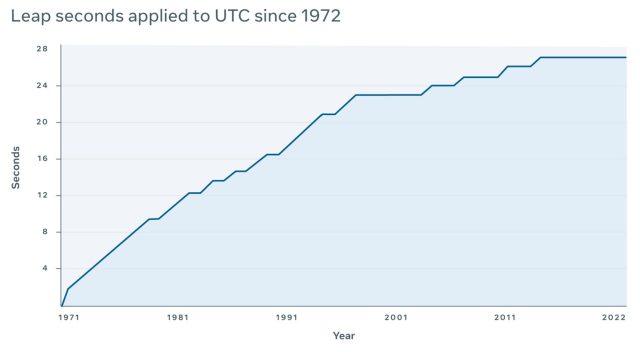

Facebook, like many large-scale tech companies, is tired of trying to time a global network of servers against leap seconds, which add between 0.1 and 0.9 seconds to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) every so many years. There have been 27 leap seconds added since 1972. In a post on Meta’s engineering blog, Oleg Obleukhov and Ahmad Byagowi say 27 is quite enough for non-solar-scientist types—"enough for the next millennium."

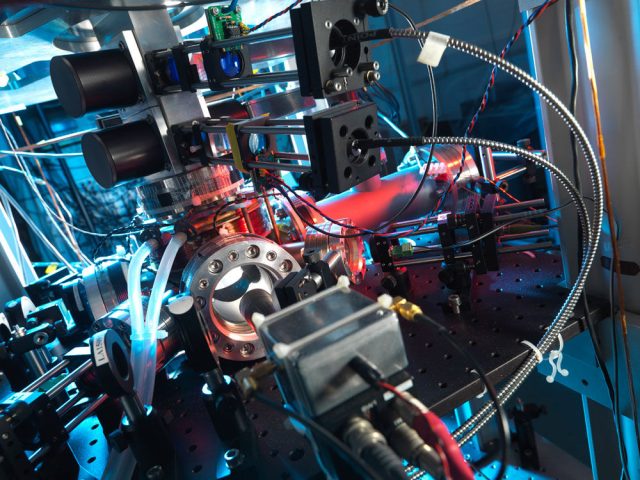

International timekeeping bodies add leap seconds at unpredictable intervals because the things that cause them—the braking action of tides on rotation, moon position, the distribution of ice caps on mountaintops, mantle flow, earthquakes—are unpredictable. When the Earth’s speed varies too much from atomic time-keeping, a leap second is called for by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS).

At midnight on the designated day, clocks are set to tick from 23:59:59 to 23:59:60 to 00:00:00. That uncommon middle timestamp drives coordinated systems bonkers. A leap second in 2012 took down Reddit, Gawker, and Australian airline Qantas. Cloudflare took the hit on New Year’s 2017 (and detailed why). Since then, many technologies have prepped themselves for the next leap second with “leap smearing,” or using micro-second slowdowns over a long, global-server-friendly span leading up to midnight.

Meta’s engineers note that, while every leap second thus far has been positive, a negative leap second—the kind computer systems might not easily “smear”—could occur due to “the Earth’s rotation pattern changing.” It’s far from idle speculation.

Earth recently experienced a record-short day on June 29, 1.59 milliseconds less than the 24-hour norm. It’s part of a general speeding-up trend. The second-shortest day (Edit: since International Atomic Time began its tracking in the late 1950s) had been July 19, 2020, at 1.47 milliseconds under, until July 26, 2022, at 1.50 milliseconds, one day after Meta's anti-leap-second post.

Leonid Zotov of Lomonosov Moscow State University told timeanddate that he believes the irregular movement of the Earth’s geographical poles could be at fault. But Zotov also thinks there’s “a 70 percent chance” a negative leap second won’t be needed, at least this year.

Arguments against leap seconds have been stacking up since the disruptions caused by the last two (with the occasional quirky dissent). The last time it came up for an official decision, in 2015 at the World Radiocommunication Conference in Geneva, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) punted the decision to 2023. The next big confab of time-keepers takes place in late 2023 in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, when a contract delegating UTC time-keeping to the ITU expires.

Meta’s call to action might not be the first, but it could end up being great timing.

reader comments

339