Japan’s tiny lunar lander never got to touch down on the Moon, as it failed to communicate with ground controllers shortly after launching aboard NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) rocket. The spacecraft was one of 10 cubesats that participated in the Artemis 1 launch, which endured several delays that may have affected the cubesats’ performance in space.

On Monday, the Japanese space agency JAXA announced that it was unable to receive radio signals from its OMOTENASHI cubesat, officially declaring a mission failure. “We will investigate the cause of this incident and proceed with the future operation plan while consulting with the relevant parties,” the OMOTENASHI team wrote on twitter.

OMOTENASHI was supposed to land on the Moon and explore its surface as the world’s smallest lunar lander. The mission launched on November 16 from Kennedy Space Center, tucked inside SLS along with 9 other cubesats.

The early morning launch kicked off the Artemis Moon program, delivering the Orion capsule on a 25.5 day journey to the Moon and back. Shortly after launch, Orion phoned home and was even able to beam back a few shots of Earth and the Moon as it began its trip.

But SLS’ secondary payload wasn’t as lucky, with only six out of 10 cubesats sending a signal to mission operators after their launch. The six cubesats that have been deemed operational so far are: Southwest Research Institute’s CuSP (for tracking the Sun’s particles and magnetic fields), JAXA’s EQUULEUS (scanning Earth’s plasmasphere), BioSentinel (for studying the effects of deep-space radiation on living organisms), and the European Space Agency’s ArgoMoon (which observed the cryogenic propulsion stage that set Orion on its course towards the Moon). Two of the missions are designed to study the Moon: Lunar IceCube and LunaH-Map.

OMOTENASHI ran into trouble early on, with JAXA stating that communication with the satellite was not stable. Two other cubesats that launched with Artemis 1 have not made contact: NASA’s Near-Earth Asteroid Scout (NEA Scout) and Miles Space’s Team Miles, while Lockheed Martin’s LunIR cubesat sent out a weak signal.

“So often, the Achilles heel of these satellites is communications,” Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, told Gizmodo in a phone interview. “That is particularly challenging for deep space missions like this.” Another factor that might have played into the cubesats’ failure to send out their signals is their battery power.

The cubesats were packed into SLS in preparation for an original launch date on August 29. However, the Artemis 1 mission endured several delays over the past few months and ground crews were only able to recharge 4 out of 10 cubesats as the rocket took shelter from Hurricane Ian. During a press conference on November 18, Mike Sarafin, Artemis 1 mission manager at NASA, said that half of the 10 satellites launched were working through a series of issues.

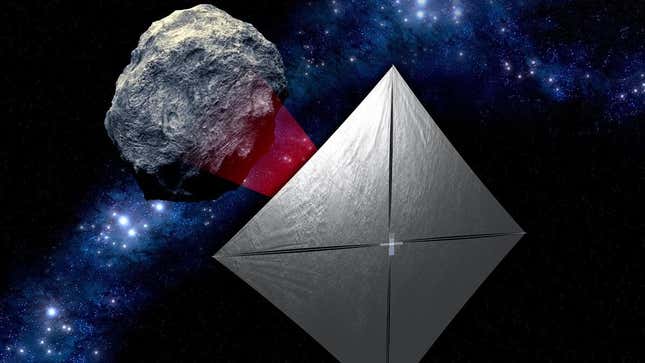

NASA was worried that its LunaH-Map cubesat would not have enough power, but it is “on path to have a successful mission,” Sarafin said. NASA’s NEA Scout mission, on the other hand, has not yet phoned home. The cubesat is designed to use solar sails to fly to a nearby asteroid, observing it up close and sending images back. “I wouldn’t expect that to fail,” McDowell said.

According to McDowell, the cubesats are all different and they’re subject to different success rates. Some cubesats are built by aerospace engineering students and those tend to have a low success rate, while others have a higher success rate as they are operationally built and used by companies. “The Artemis cubesats are a mixture,” he said. “Some of them are a bit more serious than others.”

The Team Miles cubesat, as an example, was built by a small space exploration company to demonstrate a propulsion scheme using plasma thrusters. “This sort of amateur one I might have expected to fail,” McDowell said.

But with only 6 cubesats operating normally so far, the failure rate of SLS’ secondary payload is not looking good. “Given the mix of cubesats, it’s a little higher than one would like,” McDowell said.

For the remaining three cubesats that did not phone home, they may be forever lost by now. “A lot of them were meant to make maneuvers as they passed the Moon this morning,” McDowell said. “So for them, it’s too late.” Even for the cubesats that have sent a signal so far, their success is not guaranteed. “Just saying that they got a signal from them the day after launch isn’t quite the same as saying that the mission is successful,” McDowell added. “I think there’s a lot more information that needs to roll in over the next few days.”

More: Orion Completes First Lunar Flyby and Captures Stark Image of the Moon