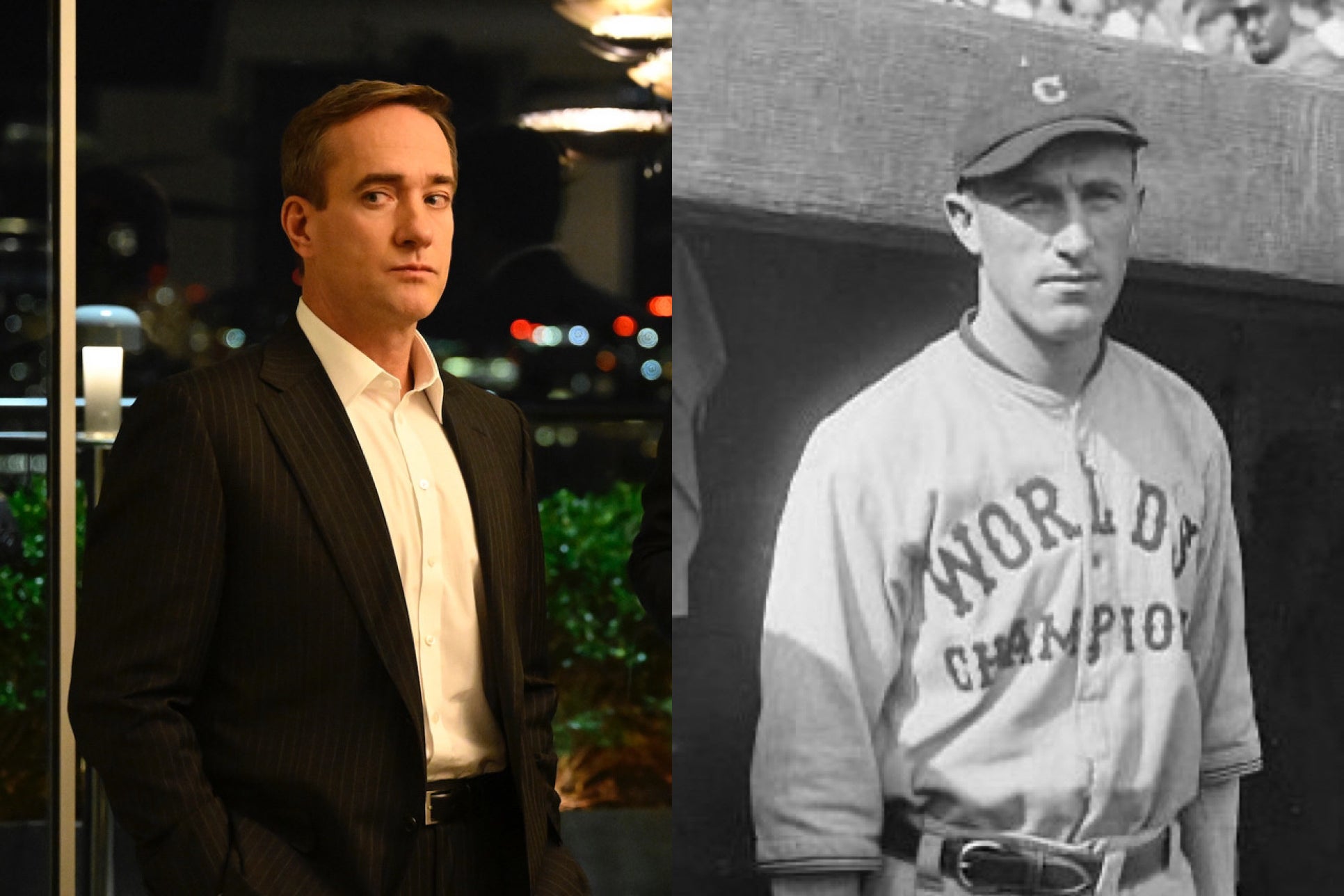

There’s been much talk on the Succession internet about the significance of the name of Tom Wambsgans, the mewling husband of Siobhan Roy, one of the claimants, with her brothers, Kendall and Roman, to the Murdoch-like family throne. In a TikTok last week that went viral, Sophie Kihm, editor in chief of Nameberry, a baby-name website, noted that Tom shared a German surname with Bill Wambsganss, who in 1920 turned the first and only unassisted triple play in World Series history.

Kihm theorized that Tom’s name was a clue that he, too, would take out three players at once to land atop the media empire. Which is what happened in Sunday’s series finale. It’s also worth noting that Tom had already done that once before, at the end of Season 3 of the show, when he snitched to patriarch Logan Roy that the kids were attempting a coup.

Kihm wasn’t the first to note the parallel names—or even propose this theory. In November 2021, Wisconsin math professor and Slate contributor Jordan Ellenberg tweeted, “Succession names: (Tom) Wambsgans is named for someone famous for eliminating three opponents at once,” and he linked to Bill’s Wikipedia entry. A month later, Vanity Fair’s podcast Still Watching mentioned the connection, citing a listener email. After the Nameberry video, media from the New York Times (“Who Was Bill Wambsganss, and Was He a ‘Succession’ Spoiler?”) to Cosmopolitan (“How Tom Wambsgans’ Last Name Literally Lays Out Succession’s Shocking Finale”) to a Los Angeles Dodgers blog (“This Succession finale theory has a shocking Dodgers history twist”) touted the name Wambsgans(s) as tipping the show’s outcome.

According to Colin Wambsgans, a composer in Los Angeles (and friend of my Slate sports podcast Hang Up and Listen co-host Josh Levin), two main branches of Wambsganses appear to have settled in the United States in the 1800s. One, in New Orleans, spelled the last name like Tom, with one S at the end, and were Catholics. The other settled in Cleveland and spelled the last name like Bill, with two S’s at the end, and were Lutherans. “So Bill Wambsganss is like a first cousin thrice removed,” he said. “Maybe. I’m probably more closely related to Tom Wambsgans.”

Bill Wambsganss was indeed born in Cleveland and was the son of a Lutheran clergyman. Wambsganss went to divinity school—reluctantly. He didn’t want to become a minister, he told Lawrence Ritter in the 1966 book The Glory of Their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball Told by the Men Who Played It, in part because he couldn’t speak in front of an audience and stuttered a little. Wambsganss lucked out. A fellow divinity student who had played pro ball recommended him to the manager of a Cedar Rapids, Iowa, minor league team, that was looking for a shortstop. “The good Lord must have really taken pity on me,” Wambsganss told Ritter.

Wambsganss joined the team in 1913. The following summer, after returning to Cedar Rapids, he was sold for $1,250 to the Major League Cleveland team, then known as the Naps, after star second baseman Napoleon Lajoie. After Wambsganss’ arrival in Cleveland, sports columnist Ring Lardner wrote a limerick about him:

The Naps bought a shortstop named Wambsganss,

Who is slated to fill Ray Chapman’s pants.

But when he saw Ray,

And the way he could play,

He muttered, “I haven’t a clam’s chance!”

Wambsganss played in the majors from 1914 to 1926, for Cleveland and Boston, and seven more seasons in the minors. His tongue-twisting surname was often abbreviated in scorecards and newspapers to “Wamby.” Some family members would later shorten their names to that.

The 1920 season was a rough one for Cleveland. Wambsganss’ longtime double-player partner, the aforementioned Ray Chapman, was killed by a pitched ball in August. “Ray always said he would never play shortstop next to anybody else,” Wambsganss said in The Glory of Their Times. “And sadly enough, that was true.”

But Cleveland, now named the Indians, played through grief and made it to the World Series, where they faced the Brooklyn Robins. The teams split the first four games of the best-of-nine series. In Game 5, Cleveland was up 7–0 after four innings, thanks in part to the first grand slam in series history, by Elmer Smith. Second baseman Pete Kilduff and catcher Otto Miller singled to start the Brooklyn fifth. The next batter, pitcher Clarence Mitchell, lined a fastball toward center field.

Wambsganss told Ritter that he “made an instinctive running leap for the ball and just barely managed to jump high enough to catch it in my glove hand.” Kilduff was running to third, and Wambsganss touched second base for the second out. Then he looked to his left. “Well, Otto Miller, from first base, was just standing there, with his mouth open, no more than a few feet away from me,” Wambsganss recalled. “I simply took a step or two over and touched him lightly on the right shoulder, and that was it.”

Fans inside League Park in Cleveland initially were confused, Wambsganss said, but “by the time I got to the bench it was bedlam, straw hats flying onto the field, people yelling themselves hoarse, my teammates pounding me on the back. … The rarest play in baseball, they say. I’m still very proud of it.” Cleveland won the series 5 games to 2.

So was Waystar Royco executive and Shiv cuckold Tom Wambsgans in fact named for Cleveland second baseman and World Series trivia question Bill Wambsganss? Did Bill’s real-life triple play foreshadow Tom’s fictional one a century later?

“I hate to spoil the internet’s fun, but it’s false,” Frank Rich, an executive producer of Succession, told me in an email. “Tom’s family name was picked before we had shot a first season”—the Succession pilot was made in 2016—“let alone mapped out precise story twists that would culminate 39 episodes later! Not to mention that many of the key writers on the show, starting with its creator, Jesse [Armstrong], are British, live in London, and are devoted to British football.”

Rich, a New York magazine writer-at-large and former New York Times columnist, added that the source for Tom’s last name is a typical one in screenwriting: A Succession staff member had a relative named Wambsgans. “If memory serves,” Rich said, “we were looking for something off-key that would be awkward to say/pronounce, befitting a character who arrives as an outsider in the Roys’ world.”

So, no baseball history connection, Succession fans. Though in the series’ very first episode, in 2018, Tom Wambsgans did tag out at home a boy whom Roman Roy offered to pay a million dollars for hitting a home run during the Roy family softball game. “Bad luck, kid,” Tom said. Makes you wonder.