Back in 2014, when actress Evangeline Lilly (Lost, The Hobbit) shared her desire to have six children in Fashion magazine, she added, “There is that old mentality where some think women should be barefoot and pregnant and in the kitchen. When I hear those words, I think, ‘What. A. Dream.’ ” British superstar singer Joss Stone echoed Lilly this past March when she revealed she wants seven kids of her own: “Sometimes I feel like I’m supposed to be born in another time, because it’s really not fashionable to say I just want to be barefoot and pregnant.”

The phrase “barefoot and pregnant” has always struck me as a vivid threat of entrapment: the one-two punch of immobilization in the domestic sphere by dint of both biology and culture. But it doesn’t have quite the same ring if you’re a millionaire celebrity. The starlets in their airy kitchens wearing designer maternity dresses and whipping up a batch of vegan hemp heart scones aren’t ensnared—they’re delighted! This is the fulfillment of a dream, this is their choice, and why shouldn’t it be?

Choice is the operative word here, and the light-hearted take on this well-worn saying doesn’t seem nearly as light in these post-Roe days. For the past century, “Keep ’em barefoot and pregnant!” has been an old boys’ club joke, a motto, a rallying cry, a wedding toast, a chain of California spas, and now, of course, a meme. Incendiary, tasteless, and provocative, it’s commonplace in American culture. But where did it actually come from?

As I cast about for an answer, I discovered a British proverb that seems to have inspired our own American variant. “Keep her well-shagged and poorly shod and she’ll not wander far,” and adaptations thereof, shows up on hundreds of internet conversation threads, social media posts, novels, and, poignantly, in this punk rock song about domestic violence. As Jonathon Green, author of Green’s Dictionary of Slang, noted in response to my Twitter inquiry about “well-shagged and poorly shod,” it’s almost always prefaced by “the old proverb,” but there’s no evidence of it predating the 20th century.

After I reached out to him with the same question, Tony Thorne, a writer and lexicographer who works as a language consultant at King’s College London, delved into the British databases but couldn’t find a definitive date of origin for the phrase either. However, he also believes that it’s likely the progenitor of our own: “I do suspect that the more vulgar, cold-blooded British version is older, but of course that sort of crude language circulated in more private settings and would have been too outrageous for national newspapers and other respectable sources in the U.K. to quote.”

Thorne raises a significant point: the inherent challenge in searching for the origin of expressions that were uttered regularly behind closed doors but deemed inappropriate for print. Perhaps this accounts for why the first instance I found of the “barefoot and pregnant” saying in the U.S. was merely “recorded,” with an ethnographic air, by a respectable source.

In 1938, Arthur E. Hertzler published his autobiography of practicing as a Midwestern family physician at the turn of the century, The Horse and Buggy Doctor. One of his anecdotes about a patient includes the following:

Some vulgar person has said that when the wife is kept barefooted and pregnant there are no divorces. Bad as this sounds, it is so because it is so near the truth; but it does not fit into our growing notion of what constitutes civilized society.

Hertzler recognizes that the saying doesn’t jibe with the way American ideals were evolving at the time, but he also acknowledges its innate logic. Keeping a woman in a state of pregnant servitude did ensure that a man maintained control over his wife, and the marriage would be more likely to remain intact. Implicit in this is her dependence on him; divorce would now be out of the question, because she and her child(ren) couldn’t survive on their own.

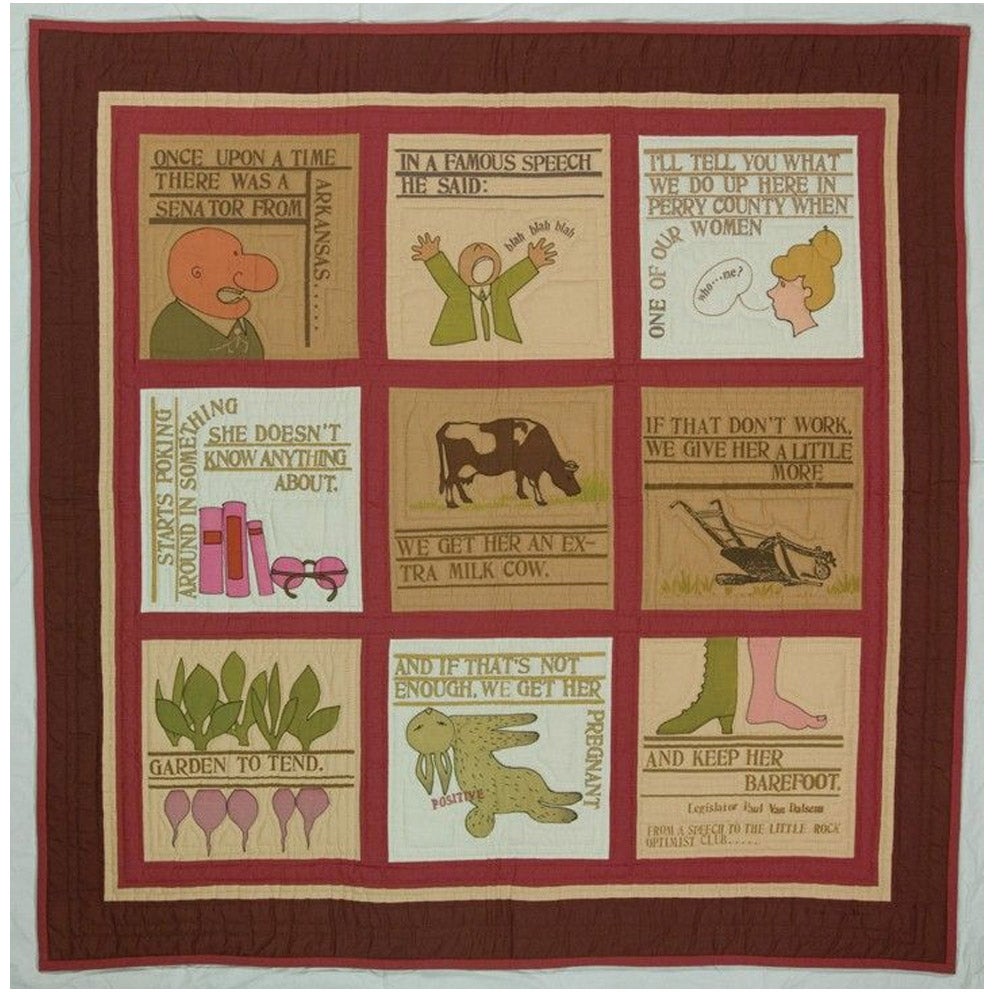

The next noteworthy appearance of the expression came 25 years later, in 1963, when it was now, apparently, acceptable in some circles to give full voice to the vulgar. Angered by the American Association of University Women, which criticized his opposition to a voter registration bill, the cigar-smoking, Southern mossback (diehard conservative) politician Paul Van Dalsem shot back with a speech to an all-male audience at the Little Rock Optimist Club:

We don’t have any of these university women in Perry County, but I’ll tell you what we do up here when one of our women starts poking around in something she doesn’t know anything about. We get her an extra milk cow. If that don’t work, we give her a little more garden to tend to. And if that’s not enough, we get her pregnant and keep her barefoot.

The remarks caused a firestorm, and Perry County women came out to protest with signs reading “Veto Villain Van Dalsem’s Vulgarity” and “Poor Paul’s Power Has Petered Out.” Others responded directly to the intimation of sexual violence and physical aggression with the slogan, “We’ve Been Pregnant—by Choice, Not by Force.” For his part, Van Dalsem, who served in the Arkansas legislature off and on for 30 years, claimed in public that he was only joking, and privately railed against the journalist who reported the remarks. He was decried as a “boor” who used “barnyard homilies,” but ultimately the speech resulted in few political repercussions, and he was reelected to the state legislature in 1964.

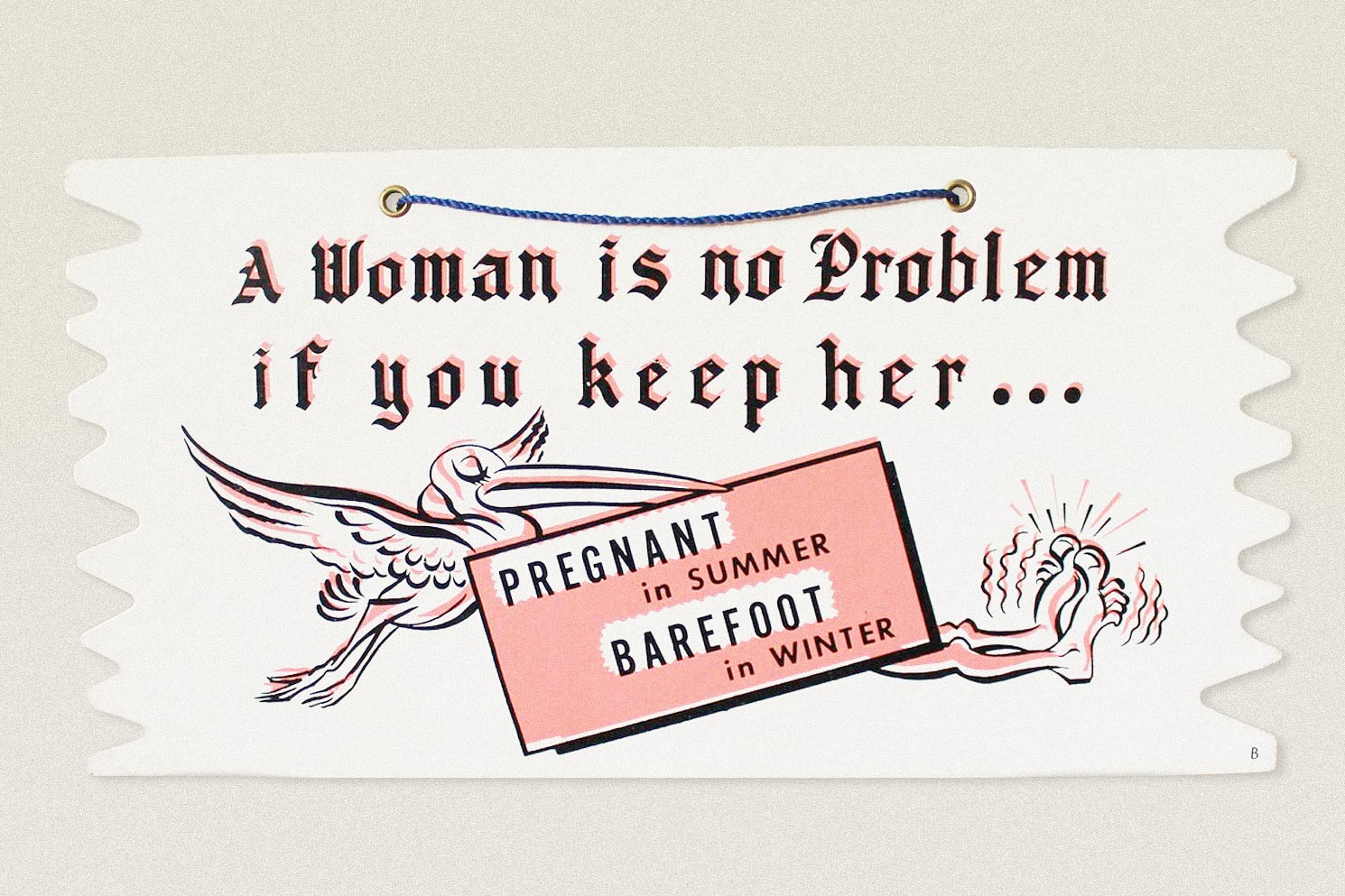

Another variation of the saying with a seasonal twist shows up in the June 1947 edition of Life magazine in an article about women’s roles titled “Woman’s Dilemma”: “She must steel herself because sooner or later some man is bound to comment, ‘a woman hasn’t any problems if you keep her pregnant in summer and barefoot in winter.’ ”

This rendering seems to inject a sinister causality into the equation, i.e., if a woman can’t escape in winter—because the snow will be too cold on her unshod feet—she won’t have a choice but to be pregnant by the summer. Self-published poet Keith Vance’s song from the ’70s, “Barefoot and Pregnant,” gestures toward this seasonal version of the saying, referring to pregnancy as a form of “branding”:

Keep ‘em barefoot and pregnant and home with the kids

no one did it better than my daddy did

twenty years later the father of nine …

keep them warm in the winter so they don’t catch cold

and branded in the summer so you know they’re at home …

Casts a new light on the image of the shoeless but heart-full earth mama traipsing through a field of wildflowers, doesn’t it? To my ears, there’s an echo of agrarianism here too, a hint of advice as to when it’s best to “breed” women, aligning them with livestock. Also, as late as the ’50s, it was not thought proper for pregnant women to be seen in public, so another interpretation of “barefoot in winter, pregnant in summer” is simply that women should be forced to stay home all the time.

The seasonal version of the saying may have been the most commonly known for a time in the U.S., and perhaps (though I couldn’t find any hard evidence) predated the pithier form that reigns today. Notably, the winter/summer variation shows up again in the record of the 1970 congressional hearings for the Equal Rights Amendment, in the statement of Wilma Scott Heide, chairwoman of the board of directors of the National Organization for Women:

We’re raising our consciousness and yours to our authenticity as persons. We will never again be satisfied to be “barefoot in winter and pregnant in summer.” We value ourselves, our children, and men too much to deprive the world of our other talents.

In addition to the British “well-shagged” version, other iterations of “barefoot and pregnant” from around the world kept popping up in my research. Originally a tenet of the German Empire, the saying “Kinder, Küche, Kirche” (“Children, Kitchen, Church”) encapsulated the ideal role of the married woman. The slogan was picked up and repurposed by Adolf Hitler, who gave a speech in 1934 declaring that a German woman’s world “is her husband, her family, her children, and her home.”

Could this be why we see the first appearance of “barefoot and pregnant” in the U.S. just a few years later? Was the zeitgeist just ripe enough for an American version to emerge? Leila Rupp, professor of feminist studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of Mobilizing Women for War: German and American Propaganda, 1939-1945, agreed that the “connection totally makes sense in terms of timing.” She added, “There was little difference in the two countries on the question of where women belonged, so the idea of keeping women in the home, and pregnant to boot, would have made cultural sense in both contexts.”

I also came across references indicating very similar, or perhaps copycat, sayings in Russian and Polish. In Spain, the common proverb, “la mujer casada, la pierna quebrada y en casa” translates as “a married woman at home with a broken leg,” and is known to have been in use before 1583. Other gems include “mujer que no para en casa, cadena en el pie y las manos en la masa”: “A woman who doesn’t stay home, feet in chains and hands in the dough”; and “la mujer y la oveja, antes que anochezca en casa”: “Women and sheep at home before dark.”

I’m left wondering if this is some kind of worldwide, misogynistic mind-meld, or did all these sayings emerge at different times from one common wellspring? Our folksy American iteration, “Keep ’em barefoot and pregnant!” seems somewhat less upsetting than the mention of chains or the threat of broken limbs, but it’s clearly in the same spirit. One thing is evident: The scheme of keeping women tied to childbearing and housework, by whatever means necessary, is not only a time-tested source of humor and folk “wisdom,” it’s got global appeal.

In 1978, with the women’s movement in full swing, Robert Claiborne, the well-known scholar of the English language, optimistically declared “barefoot and pregnant” a “semi-proverbial recipe for marital happiness … [an example of] male callousness to women—now, happily, all but extinct.”

Who could have guessed how wrong he’d be?