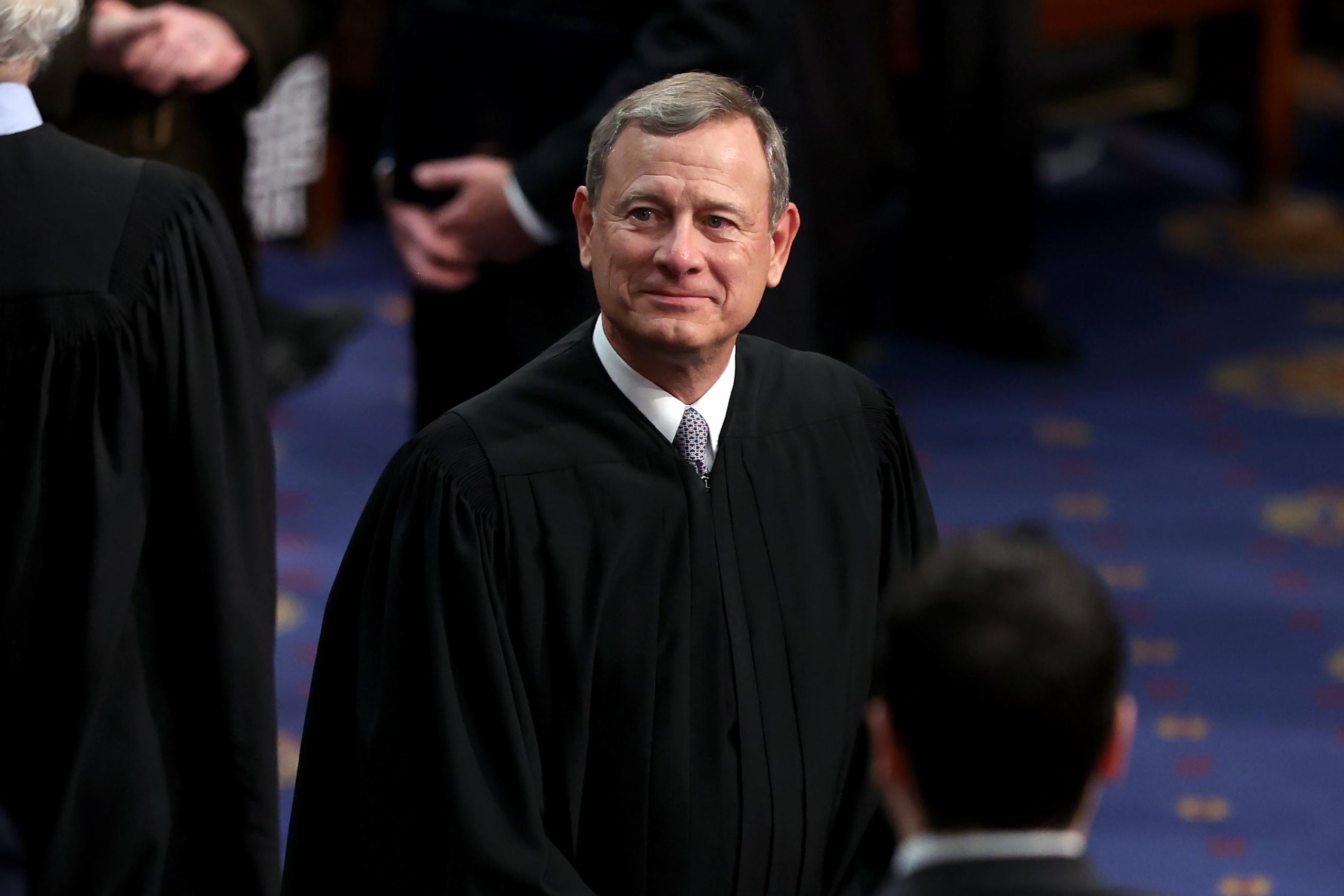

The Supreme Court divided 5–4 in a clash over religious liberty and LGBTQ equality on Wednesday, forcing Yeshiva University to stop discriminating against a gay rights group on campus. But the majority’s order had little to do with this culture-war skirmish. Instead, it was a rebuke of Yeshiva—and specifically, its overeager lawyers—for racing to SCOTUS after losing in the lower courts because of their own errors. Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh did not side with the three liberals against the university because they think gay students deserve equal treatment. They did so because Yeshiva brazenly abused the court’s shadow docket on the assumption that it would get special treatment. It was an understandable gamble. But it failed.

Yeshiva University v. YU Pride Alliance arose after the school denied official recognition to a student group that affirms the equal dignity of LGBTQ people. Yeshiva calls itself a Jewish university; however, it is incorporated as a secular institution in order to receive government funds, and fewer than 5 percent of students major in Jewish studies. The LGBTQ student group accused the school of violating the New York City Human Rights Law and sued for formal recognition. Yeshiva argued that it was exempt from the Human Rights Law because it is a “religious corporation”—and added that if the law did apply, it violated the First Amendment’s free exercise clause.

A state trial court sided against the university in June. The court held that New York City’s Human Rights Law does apply, noting that Yeshiva’s own charter says it operates “exclusively for educational purposes,” not religious training. The university sought relief from an intermediate appeals court called the First Department, which turned it down.

Yeshiva then tried to appeal the First Department’s order to New York’s highest court. In the process, it made a mistake, one that’s fairly technical but still important. State law requires a party to ask the First Department for permission to appeal an order; Yeshiva failed to do so properly, filing the wrong application. The First Department informed the university of its error and instructed it to refile the correct application. After that, it could appeal to the state’s highest court—then, if necessary, to SCOTUS.

However, lawyers representing the university did not want to play by New York’s rules. They were hoping to score a quick win, and it’s easy to see why. To fight the LGBTQ student club, Yeshiva hired the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a right-leaning group with a strong track record at this Supreme Court. As an impact litigation firm, the Becket Fund seeks to rack up high-profile victories that’ll attract more acclaim, donors, and clients. With every win, Becket grows more entrenched and respected within the conservative legal movement. It apparently aims to become a marquee litigation shop for the religious right, one on the level of the Alliance Defending Freedom, despite having a small fraction of ADF’s budget.

Moreover, Becket had good reason to believe it could short-circuit the appeals process in New York state courts. This Supreme Court has shown extraordinary solicitude to religious liberty claims, most prominently in cases halting COVID restrictions on houses of worship. The conservative justices have repeatedly changed the court’s own rules to carve religious exemptions into law. They have exploited the shadow docket to skip over full briefings and oral arguments, sometimes acting before a lower court even issues a decision. The Becket lawyers evidently assumed that they could secure this special treatment for their client, too.

This time, though, they went too far. Under federal law, the Supreme Court can only stay the “final judgment” of a state’s highest court. But there’s no final judgment here: New York’s highest court is waiting for Yeshiva’s lawyers at the Becket Fund to correct their error and refile, teeing up a proper appeal. These lawyers were really asking SCOTUS to bend the rules just for them, and it backfired: Roberts and Kavanaugh sided with Justices Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, and Ketanji Brown Jackson in swatting down their emergency application. The majority pointed out that Yeshiva still had options in state court—most importantly, filing “a corrected motion” that would put their case before New York’s high court. It could also seek “expedited review” to speed up consideration of the merits. If the university pursues these options and still fails, the majority wrote, it could return to SCOTUS with another request for a stay.

Predictably, Justice Samuel Alito penned a dyspeptic dissent, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett, accusing the majority of shirking its “duty to stand up for the Constitution even when doing so is controversial.” Notably, Alito’s dissent focused on the merits of the case: He accused New York of forcing “a Jewish school to instruct its students in accordance with an interpretation of Torah that the school, after careful study, has concluded is incorrect.” (It’s unclear how requiring Yeshiva to grant equal recognition to a gay student club forces it to “instruct its students” on anything.) “A state’s imposition of its own mandatory interpretation of scripture is a shocking development that calls out for review,” the justice huffed.

Alito claimed that Yeshiva has a clear First Amendment right to discriminate against LGBTQ students under settled law, which would justify an emergency stay. Is that true? Under existing precedent, maybe not. Religious organizations do have a right to autonomy over their internal management decisions, particularly those fraught with faith-based judgments. Yeshiva, though, may have relinquished that right when it chose to incorporate as a secular institution. This Supreme Court will likely rule for the school in the end, but this area of the law is far from settled. In 1987, for instance, the District of Columbia’s highest court ordered Georgetown University, a Catholic school, to provide equal benefits to a gay student group. Alito wanted to seize on the Yeshiva case to establish new precedent handing educational institutions a newfound religious right to discriminate, and he was willing to overlook Yeshiva’s own legal mistakes to do it.

Why did Roberts and Kavanaugh draw the line here? Presumably, they could not bring themselves to sanction such an egregious abuse of the shadow docket. The chief justice has, to his credit, already expressed dismay over the ultraconservative majority’s freewheeling use of emergency orders to reshape the law. Kavanaugh is the surprise here: He’s usually part of the problem, but he cast the key vote to stop his colleagues from indulging Becket’s extravagant demands.

Perhaps Kavanaugh is having second thoughts about the exponential increase in shadow docket orders since he joined the court. This radical departure from the court’s long-standing norms has created the impression that certain litigants—the Trump administration, Republican attorneys general, religious objectors—deserve more consideration than others. It has also opened the door to an endless stream of emergency applications from parties who do not want to wait weeks, months, or years for resolution. The majority inadvertently incentivized these rushed requests by granting so many of them when there was no legitimate basis to do so. Lawyers took note: Why slog through the lower courts when you can get immediate relief from SCOTUS?

The surge in shadow docket orders since 2018 is unsustainable. There’s no way nine justices can handle a nonstop glut of so-called emergencies that demand instant action. Wednesday’s order may have been Roberts and Kavanaugh’s way of telling conservative lawyers to stop asking SCOTUS for a sweetheart deal when they don’t want to put in the work and wait their turn.