“We have to talk about Baby A.”

When the doctor finally came in, I was aware something was wrong. I was pregnant with twins and 37 years old, so we’d had many ultrasounds before. But something was taking too long. The ultrasound techs were usually cheerful and chatty, but this one kept asking how far along I was and remeasuring Baby A’s head.

I was well aware from my time as an abortion lawyer that many terrible things can be discovered at the 20-week scan. But somehow it just seemed too on the nose for one of those terrible things to be happening to me.

Baby A had enlarged ventricles in his brain. This could mean nothing and resolve on its own, we were told. Or it could require surgery. Or it could be a symptom of a condition that is, as they say, “incompatible with life.” Baby A’s condition was also a potential threat to Baby B.

They gave me amniocentesis and ushered me and my husband to a genetic counselor. The counselor raised the possibility that we needed a “selective termination.”

Then she told us we didn’t have a lot of time to decide because 24 weeks was the legal cutoff to have an abortion in New York. I had the impulse to argue with her—to explain that the abortion law then in place in New York predated Roe v. Wade and was technically unconstitutional (this was 2017, when Roe was still the law). I wanted to tell her abortion could not be banned prior to viability and that whether a fetus is viable—meaning, theoretically able to live outside of the womb—is a medical determination specific to each particular pregnancy.

But I did not launch into a soliloquy on abortion law, probably because I did not want an abortion. Also, I knew that it doesn’t matter if the law arguably permits an abortion if no hospital will give you one. But the counselor’s warning grated on me—there was something so awful about having to consider the law while trying to process this news.

The next day, my husband and I rented a car and drove an hour out of town to a fetal MRI specialist.

The results: The baby’s brain wasn’t “mush,” as the doctor put it. If things got worse, however, excess fluid could escape Baby A’s brain, causing me to go into early labor and potentially lose them both. We had less than four weeks to decide what to do.

The results were as good as we could have hoped for. I threw up out the window of the rental car all over the West Side Highway on the way home.

No one wants to have an abortion when they are far into a pregnancy. People with unwanted pregnancies prefer to have abortions as early as possible. This is why approximately 95 percent of abortions happen before 15 weeks, when a fetus is about the size of an apple.

People have abortions after the first trimester when something has gone very wrong: a medical tragedy, being too young to recognize one is pregnant, or being unable to get the money, child care, or time off of work to travel to a clinic at an earlier stage.

But Republicans tell us there are people who wish to have abortions “up until birth” and who must be stopped by force of law. In September, RNC chair Ronna McDaniel advised Republican candidates to accuse Democrats of having a policy of “due date abortion.” Marco Rubio, Ron DeSantis, Blake Masters, Kari Lake, Doug Mastriano, Herschel Walker, Ron Johnson, and many more did so, claiming on the campaign trail that some people want abortions “up until birth.” Mehmet Oz, in a debate last week with John Fetterman, argued his opponent would “allow abortion at 38 weeks, on the delivery table.”

The strategy is clear. Republicans must distract from the crisis that is the end of Roe, as well as the many unpopular bans enacted since the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health decision in June. In order to frame supporters of Roe as the extremists, they pretend there exist women who are such vile monsters that they would carry a healthy baby to term and then try to abort it “up until the moment—and after—birth,” as House Republican Conference chair Elise Stefanik put it in September. The logic, insofar as there is logic to this, is that allowing post-viability abortion to save the life or health of the patient—as Roe required—amounts to supporting abortion “up until birth” because patients will lie about their health in order to abort viable babies for frivolous reasons.

Back at home, in 2017, I called the genetic counselor and asked if people often had to decide whether to terminate a pregnancy before they had all the information they should. “Unfortunately, that does happen,” she told me. She was sympathetic, but she had little hope for us, noting our complicated genetic histories. (My husband and I have three cousins between us who did not survive childhood.)

At 23 weeks, we met with a pediatric neurologist to prepare us for life with a disabled child, should Baby A survive. Instead, he gave us an even worse diagnosis. I was panicked, but skeptical. I’d gone from being scared about the babies’ lack of motion to feeling like aliens were wrestling in my belly. This didn’t seem consistent with the terrible condition the doctor described.

I spoke to an attorney friend who knew more about abortion in New York, a supposedly super-blue state, than I did. She confirmed I really wouldn’t be able to get an abortion in-state if I waited but encouraged me to do what I needed to do. If things got worse, I could go to Maryland or Colorado. I knew this meant going to LeRoy Carhart or Warren Hern, two of the four or so doctors in the country who were openly providing third-trimester abortions despite constant harassment and threats to their lives. I’d read about the torturous experience of a woman who’d had to fly to Dr. Hern in Colorado just to receive the shot to induce demise in her baby with a fatal condition before returning to New York to endure 24 hours of labor to remove her dead baby. I’d written about what anti-abortion activists had done to the family of a fellow New Yorker whom Dr. Carhart couldn’t save. Not great options, but they were, ultimately, options. We decided to blow past New York’s deadline.

Now that Roe is gone, Republican politicians and other abortion opponents are arguing that even that legal landscape was too permissive. Perhaps you think I’m being unfair. Surely they aren’t talking about people in my situation?

Well, let’s consider some actual proposed legislation: When Sen. Lindsey Graham put out his proposed federal ban on abortion at 15 weeks, he did not include an exception for fatal fetal anomalies, or exceptions for the removal of a fetus that is dying, but not yet dead. Nor did his bill delineate how immediate the threat to a patient’s life must be for treatment to be legal. Now, writing a bill that would make exceptions for all the things that can go wrong in a pregnancy would be basically impossible—but Graham didn’t even try.

At his press conference announcing the bill, a woman named Ashbey Beasley (who survived the Highland Park shooting with her 6-year-old son and was in Washington to support gun control legislation) asked Graham what he would say to someone who finds out at 16 weeks, as she did, that her baby has a fatal fetal anomaly. Graham displayed not a shred of empathy for Beasley in his nonresponse and appeared to deny having any responsibility to address the practical implications of his bill.

Graham needn’t bother to improve upon the dangerously poor drafting of the state-level abortion bans that are causing so much harm to people with pregnancy complications because it is not a good faith attempt to end abortions after 15 weeks. What the bill actually does is elevate a claim for which there is no evidence: that people choose to have abortions after 15 weeks when they could have or should have had them earlier. (Indeed, with the advent of medication abortion, we could make it the norm to end unwanted pregnancies as soon as a person suspects she is pregnant—but anti-abortion activists don’t want that either.)

The reality is, after the Dobbs ruling, clinics in states where abortion remains legal have been overwhelmed with patients from out of state, predictably resulting in more abortions after 15 weeks. A person who has been forced by legal barriers to end a pregnancy at a later gestation than she feels is appropriate, or at a point when the simplest and safest early abortion options are no longer available to her, has had her bodily integrity violated—she has not made a choice to have a late abortion.

Unfortunately, lying about later abortion works. Various polls have found support for 15-week bans at 37 percent, 48 percent, and 77 percent. I’ve heard smart, kind people who consider themselves pro-choice casually repeat the claim that there are extremists on both sides because some Democrats want abortion “up until birth.” One pro-choice friend reached out to me during the 2020 campaign shaken because she thought abortion at eight months might actually be a Thing.

These misperceptions are intended. Anti-abortion lawmakers and activists know more about abortion than the average person. But they vilify the people forced by medical circumstances or anti-abortion laws to have later abortions because even in the many states where legislators have banned abortion from the moment of fertilization, criminalizing all abortion is not popular. Early abortion is acceptable to much of the general public, so the people who have those make less useful targets.

I was hospitalized three times during my pregnancy. My condition deteriorated, but Baby A’s did not. I had an array of complications, but made it to 33.5 weeks before my water broke, and I gave birth to two baby boys.

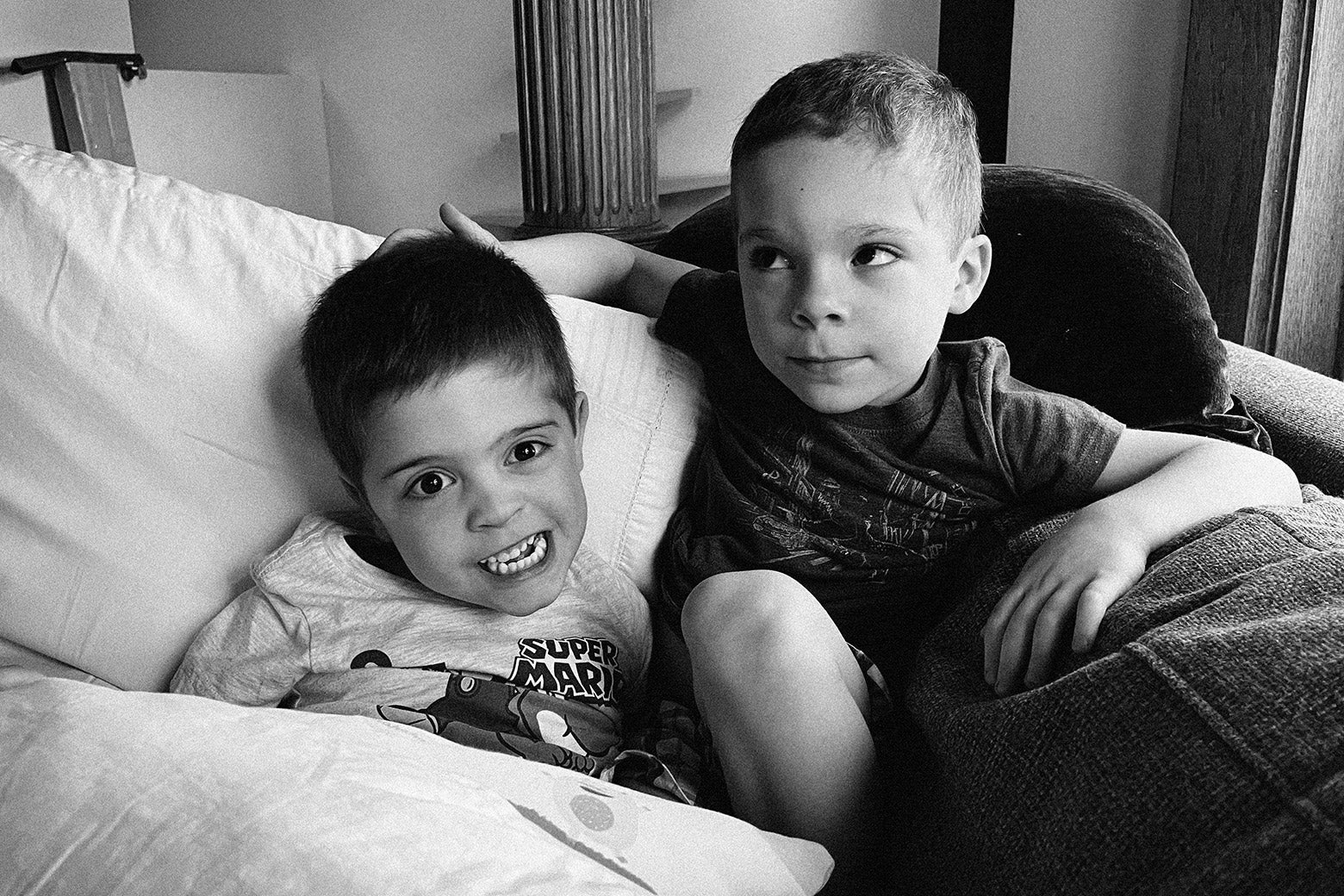

Their NICU stay was the most exhausting experience of my life, but after two weeks, my premature but relatively healthy babies came home. Baby A has grown into a creative, opinionated little kid who still refuses to stop wrestling his brother. He has a slightly larger-than-average cranium—probably unrelated to how the heck he’s reading at 4 years old.

Most parents up against a gestational cutoff cannot take the risks my husband and I did. I owe my sons’ lives to the bravery of a few doctors I knew were out there, should I need them. And to my privilege. I could rely on having a late termination because I was unusually knowledgeable about abortion, could call people who knew even more than I did, and could come up with the money for travel out of state and a procedure that can cost more than $10,000.

We do not need a law to stop later abortion in this country. Patients should be permitted to wait and pray as I was able to. In fact, we need more providers of third-trimester abortion for people who are losing wanted pregnancies, and much better access to very early abortion for those who do not want to be pregnant. Instead, the “up until birth” accusers are using the tragedies of those who didn’t want abortions to take away the right from those who do.