On April 25, Chief Justice John Roberts sent the Senate Judiciary Committee a “Statement on Ethics Principles and Practices” signed by all nine justices. Roberts forwarded along the “statement” in lieu of testifying before the committee, and obviously hoped it would quell growing congressional concern over the Supreme Court’s growing ethics scandals. The document identified various recusal and disclosure practices, claiming that “all of the current Members of the Supreme Court subscribe” to these suggested rules.

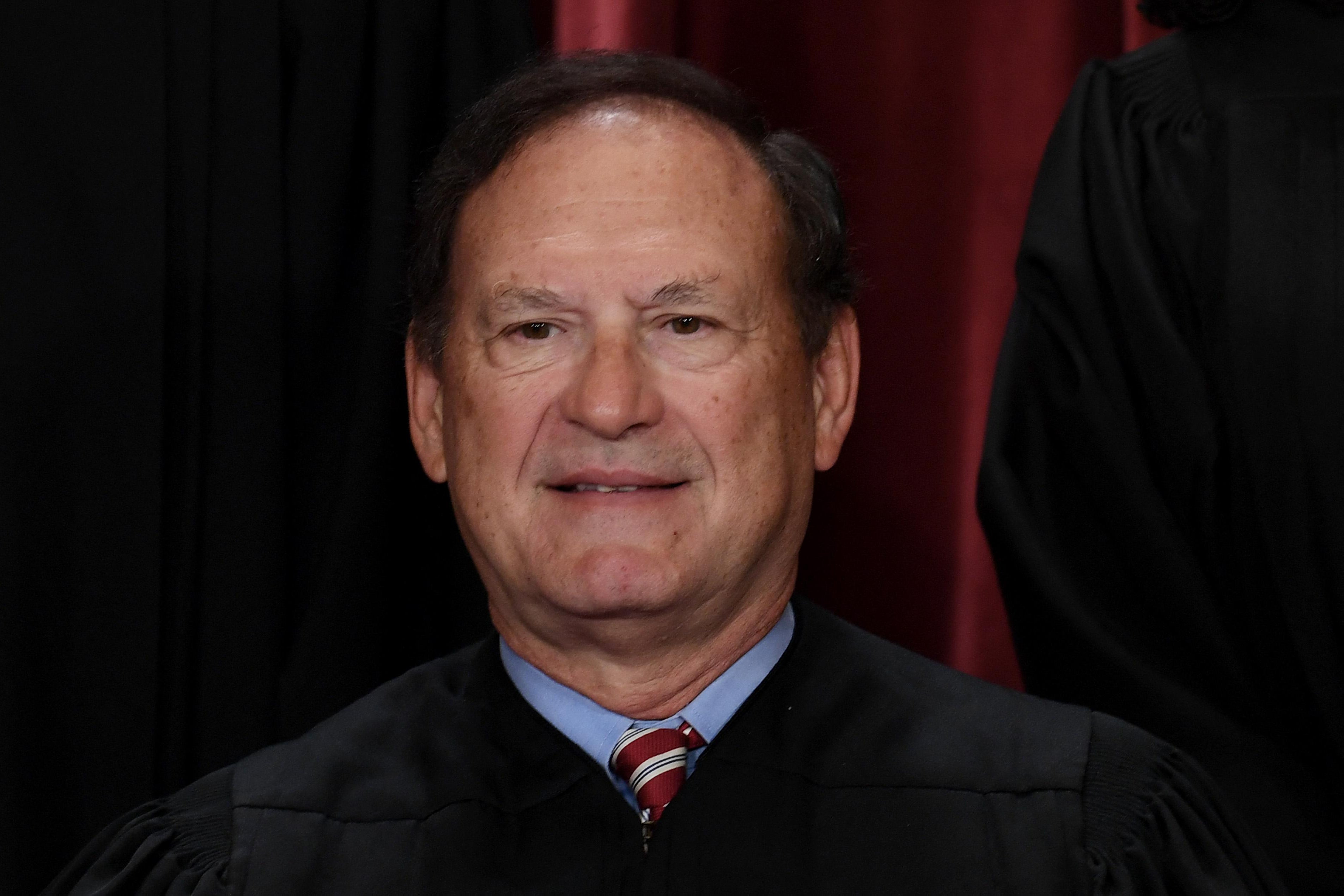

It took Justice Samuel Alito barely a month to violate them.

In the court’s orders list on Tuesday, Alito noted his recusal from BG Gulf Coast and Phillips 66 v. Sabine-Neches Navigation District—a case about two energy companies shirking their obligation to help fund improvement of a waterway that they use for shipping. (The court declined to take up the case, leaving in place a lower court decision against the companies.) But the justice did not explain his reason for recusing, one of Roberts’ promised “practices.” To obtain that information, you must dig through his financial disclosures, which reveal that he holds up to $50,000 of stock in Phillips 66, one of the parties. Alito is one of two sitting justices who still holds individual stocks (as opposed to conflict-free assets like mutual funds). The only other sitting justice who maintains investments in individual stock is Roberts himself.

For years, Alito has periodically recused from cases involving energy companies without explaining why. This spring, however, that practice was supposed to change. Roberts’ ethics “statement” explained that justices “may provide a summary explanation of a recusal decision” with a citation to the relevant provision of the Judicial Code of Conduct. (That code is binding on lower court judges but voluntary for the justices.) The “statement” offered this example: “Justice X took no part in the consideration or decision of this petition. See Code of Conduct, Canon 3C(1)(c) (financial interest).”

In Philips 66, it appears that Alito should have cited his “financial interest” in a party to explain his “recusal decision.” (In other words, he should have been “Justice X.”) This could have been a textbook example of the new rule in action; indeed, it was literally the example that the court offered the Senate Judiciary Committee. Instead, Alito refused to adhere to this new procedure.

His decision is all the more brazen given that Justice Elena Kagan debuted the new rule just last week. In recusing from a case, Kagan cited her “prior government employment,” a shorter way of saying that she participated in the proceedings while serving as solicitor general. This move provided some basis to hope that the court really had begun to embrace a modicum of transparency (albeit by doing the bare minimum). As Leah Litman pointed out on the Strict Scrutiny podcast, though, Kagan was never the problem: She has long complied voluntarily with the Judicial Code of Conduct, so much so that she once turned away a gift of free bagels and lox from high school friends. The real question was whether any justices at the center of the ethics maelstrom would follow through on the promises of the court’s “statement.” It seems the answer is no.

Which is, of course, the entire problem with the unenforceable ethics guidelines that the chief justice offered up to the Senate Judiciary Committee in place of an actual code. The “statement” declares at the outset that it contains “foundational ethics principles and practices”; you might assume that if an ethics principle is “foundational,” then every justice should feel compelled to follow it. Yet the guidelines use voluntary language throughout, hedging at every turn to avoid committing the justices to any explicit mandate. For example, the recusal provision at issue in Phillips 66 contains a hazy qualification that “in some cases, public disclosure of the basis for recusal would be ill-advised,” giving the example of “circumstances that might encourage strategic behavior by lawyers who may seek to prompt recusals in future cases.”

Whatever that hedge means, it surely does not apply here. Alito either owns stock in a party or he doesn’t, making recusals straightforward and difficult to game. But the justice’s defenders might cite that qualification—which is ambiguous to the point of meaninglessness—in his defense.

That leads to a deeper problem: The justices who commit the most ethics violations are also the least likely to follow voluntary ethics guidelines. Alito has made it clear that he thinks ethics are for chumps. The justice stands accused of leaking the decision in 2014’s Hobby Lobby to anti-abortion activists who infiltrated the Supreme Court Historical Society. Alito has delivered inappropriate public remarks swinging back at critics in the press and academia. And his track record on recusal has been spotty at best, with the justice either overlooking conflicts of interest or changing his mind about them: In 2014, for instance, the justice recused then un-recused himself from two cases without offering a word of explanation, and has failed to recuse in several cases since, despite owning stock in a party.

An ethics “statement” that does not bind Alito—or Clarence Thomas, or any other justice who holds the arrogant conviction that they have a right to do anything they want in total secrecy—is worse than useless. It creates the false impression that every member of the court is committed to the same rulebook, which in turn suggests that Congress has no need to impose an actual, enforceable code of ethics on SCOTUS. Roberts’ “statement” was designed to persuade us that the court could be trusted to keep its own affairs aboveboard. Barely a month later, it is already proving the opposite.