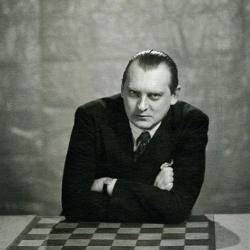

Alexander Alekhine

Bio

Alexander Alekhine is easily one of the greatest chess players of all time. Occupying a place on many people’s top-10 best-ever lists, the fourth official world champion held the title for 17 years—second only to Emanuel Lasker. He’s the only world champion to die with that distinction.

Alekhine’s chess brilliance extended to every aspect of the board and beyond. He’s best known for his tactical prowess and ability to produce combinations in complex situations. Yet, Alekhine was superior in quiet positions and endgames as well. His influence on theory is undeniable. Several opening variations bear his name, with the most notable being Alekhine’s Defense (1. e4 Nf6). Alekhine wrote more than 20 books on chess, and two of them are regularly mentioned among the best chess books of all time.

- Youth And Early Chess Career

- Alekhine's First World Championship

- Losing And Recapturing The World Title

- Legacy

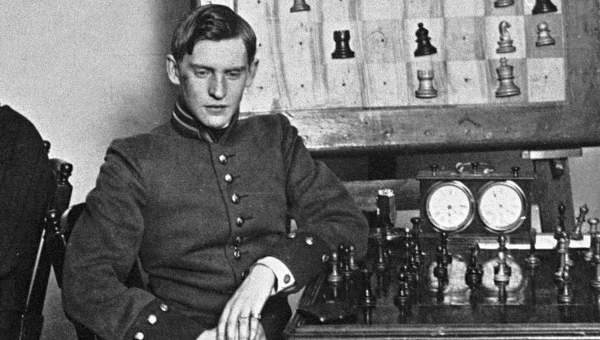

Youth And Early Chess Career

Alekhine learned how to play chess when he was six or seven years old. However, he didn’t get too involved in the game until a couple of years later when he was impressed by a simultaneous blindfold exhibition involving his older brother. On December 1, 1902, leading American player Harry Nelson Pillsbury broke his own blindfold simul record (21 opponents) by playing against 22 opponents—with 17 wins, one loss, and four draws—which inspired the young Alekhine to surpass that feat.

Alekhine could play blindfolded by the age of 12. Although he was too young to be admitted to a chess club, he developed his skills quickly through correspondence play. It took him only a few more years to accomplish his first major success. In 1909, Alekhine took first place at the All-Russian Amateur Tournament. Alekhine showed signs as a world-class player over the next few years. In 1910 he gave his first simultaneous exhibition (15 wins, one loss, and six draws) and tied for seventh out of 16 players in the elite Hamburg chess tournament behind the likes of Carl Schlechter, Frank Marshall, and Aaron Nimzowitsch. The next year he played in another strong event, the Carlsbad 1911 chess tournament, sharing seventh-eleventh out of 26 players, behind all-time greats such as Akiba Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch, and Schlechter.

In 1912 Alekhine took first at the Nordic Masters Congress in Stockholm, and in 1913 he placed first in Scheveningen (ahead of David Janowsky, Gyula Breyer, and others); however, he proved himself as an elite player in 1914. In January 1914 he tied for first with Nimzowitsch in the All-Russian Masters Tournament, and consequently, both players were invited to play in the legendary St. Petersburg 1914 chess tournament, which attempted to bring together 18 chess stars who had won major chess events. Alekhine tied for fourth/fifth place with Marshall out of 11 players in the preliminary section and performed even better in the final section. He placed third behind only the world champion Lasker and Jose Raul Capablanca. Some other top names from the event include Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch, and Joseph Henry Blackburne.

The next period of Alekhine’s chess career was marked by personal struggle. He was winning at a tournament in Manheim, Germany, when World War I broke out. The tournament was stopped, and Alekhine received the prize for first place, but a series of events interfered with chess. A declaration of war against Russia occurred, and Alekhine, along with other Russian players, were interned. In a few weeks, Alekhine obtained permission to return home, while some others (like Efim Bogoljubov) had to stay in Germany for several years.

In 1915 Alekhine started his voluntary service in the army as a medical assistant. In 1916 he was shell-shocked during the evacuation of the wounded from the battlefield. During the war, he occasionally gave blindfold simuls in hospitals. During 1919-1921 he worked as a lawyer and interpreter in various Soviet institutions. His chess was reduced to off-hand and handicap play, several small matches, the 1919-1920 Moscow City Chess championship (which he swept with a perfect 11/11 score), and the All-Russia Chess Olympiad in October 1920 where he also went undefeated. This tournament was retroactively considered the first USSR Championship. The renaissance of chess activity in Europe was a call to emigrate for Caissa's chosen.

Alekhine’s First World Championship

In 1921 Alekhine made a remarkable return to the international scene by winning tournaments in Triberg, Budapest, and The Hague with a cumulative score of 19 wins, 12 draws, and no losses. In Budapest, he employed the famous Alekhine Defense for the first time. In 1922 in London he took second place behind the new world champion, Capablanca. It was at this tournament that Alekhine and several other leading players signed the "London Rules" suggested by Capablanca for the world championship negotiations. These rules were called the "golden wall" by some contemporaries who considered the financial conditions unmatchable.

In the beginning of 1924, Alekhine played blindfolded against 26 players in New York—breaking the record that inspired him to take chess seriously. He broke his own record in the following year in Paris by playing a blindfold simultaneous exhibition against 28 opponents. In March-April 1924 he took third in the elite New York tournament behind Lasker and Capablanca—a bizarre replication of the 1914 St. Petersburg tournament finish. His book about the 1924 New York tournament is considered a true masterpiece. In 1925 he won a major tournament in Baden-Baden and completed his thesis to become a doctor of law.

During August-December 1926, he took a long trip to Argentina where he gained the financial support of the local government for a new world championship match. Already as a candidate, he took second place at the 1927 New York tournament (behind Capablanca).

Alekhine successfully played his first world championship match against Capablanca after years of trying to organize one. In Buenos Aires, Alekhine defeated Capablanca in the longest championship match ever played up to that time. Alekhine scored six wins, three losses, and 25 draws. It was shocking as Alekhine hadn’t previously won against Capablanca. Alekhine studied his opponent’s games before the match and found Capablanca’s weaknesses—then proceeded to use Capablanca's style against him. The 34th and final game took four days, with adjournments, and remains a classic example of a grind-it-out win from the fourth world champion.

Alekhine and Capablanca never had a rematch for the world title. Alekhine insisted that Capablanca provide the same financial conditions for their rematch, although he gave significant discounts to other challengers. The negotiations for the Alekhine-Capablanca rematch dragged on for years and were never finalized.

From 1927 to the mid-1930s, Alekhine dominated chess. His tournament wins during this period were extensive, and they’re highlighted by the San Remo tournament in 1930 (3.5 points ahead of Nimzowitsch) and Bled in 1931 (5.5 points ahead of Bogoljubov). In 1933, Alekhine again broke his own blindfold chess record by playing against 32 people simultaneously.

Losing And Recapturing The World Title

Alekhine successfully defended his title twice against Bogoljubov. Each time, he won easily; in 1929, Alekhine had 11 wins, five losses, and nine draws, while in 1934, he scored eight wins, three losses, and 15 draws.

Another title defense occurred when Alekhine faced Max Euwe at the 1935 World Chess Championship in the Netherlands. Alekhine started out strong, winning the first game in brilliant style and next leading five games to two. However, Euwe evened the score after seven more games and continued to narrowly win the match with nine wins, eight losses, and 13 draws.

After losing the match, Alekhine had uneven results in tournaments leading up to his rematch with Euwe. The rematch happened quickly, and the two faced each other just two years later. Alekhine defeated Euwe easily, regaining his title with 10 wins, four losses, and 11 draws. That would be the final championship match Alekhine would play. He and Capablanca couldn’t come to terms, and Alekhine passed away in 1946 while finalizing a world championship match with Mikhail Botvinnik.

After regaining his world title in 1937, Alekhine accomplished several tournament victories. However, his career was interrupted by another world war and more chaos in his personal life. Most notable were accusations of anti-Semitism, although many sources point out how Alekhine agreed to cooperate with the Nazis during World War II to protect his wife when she wasn’t granted an exit visa from France. Anti-Semitic articles appeared under his name, but Alekhine claimed that they were forged. Nevertheless, Alekhine stayed in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II, playing and winning multiple events. In 1945-1946 he was on a wanted list as a collaborationist in France and had to stay in politically neutral Spain and Portugal.

Hours after he completed arrangements on a world championship match with Botvinnik, Alekhine was found dead in a hotel room in 1946. The circumstances surrounding his death are still debated today.

Legacy

Alekhine was a brilliant tactician who excelled in all areas of the game. He beat the world’s best during a golden age of chess and also served as the precursor to the Soviet school of chess that more-or-less officially began with Botvinnik. Garry Kasparov once noted how he “admired the refinement of his [Alekhine's] ideas, and I tried as far as possible to imitate his furious attacking style with its sudden and thunderous sacrifices.”

Alekhine is one of the greatest chess players ever, but his legacy doesn’t stop there. It’s only fitting that a top-10 player of all time authored a book (My Best Games of Chess) regularly mentioned among the top-10 chess books of all time. That work and his New York 1924 masterpiece remain strong influences on the chess world, in addition to his games and contributions to opening theory.