Story highlights

No national delegates are actually at stake in Iowa's January 3 caucuses

The caucuses are primarily a game of media expectations

George H.W. Bush beat expectations by winning Iowa in 1980, helping to earn a spot on Reagan's ticket

Mitt Romney is trying to keep expectations low in Iowa -- never easy for a front runner

As you’re being inundated with wall-to-wall coverage of the Iowa caucuses this week, keep the following number in mind: zero.

The quest for the GOP’s presidential nomination is ultimately a race for delegates. With 2,286 delegates attending the party’s national convention in Tampa at the end of August, the backing of slightly over half of that group – 1,144 – will be needed for Mitt Romney, Newt Gingrich, or someone else to capture the prize.

Guess how many of these delegates will be selected in Iowa on January 3. Zero. Zip. Zilch. Nada.

Iowa matters for one reason only: the media says so. It’s been deemed the first “real” contest on the presidential nominating calendar, and for some reason “first” warrants wall-to-wall coverage. The winner – or perceived winner – is almost certain to get a campaign cash boost and ride a tidal wave of media-fueled momentum.

“Big Mo,” as George H.W. Bush once famously called it, can be a game changer.

Want to know what really happens in Iowa in January? Not much. A few thousand people who care enough about politics to spend an evening at their local library or church basement will decide who gets to attend the state GOP’s county conventions in March.

They’ll also participate in a non-binding presidential preference vote. (“Non-binding” means the state’s national convention delegates do not have to vote according to the preferences of caucus participants.)

And that’s about it.

In March, the county convention delegates will decide who attends a bunch of congressional district meetings and a statewide convention in late April and June. That’s when most of Iowa’s 28 national convention delegates — a bit over 1% of the total number of delegates in Tampa — will actually be chosen. If there’s already a likely nominee by that point, you can bet Iowa won’t rock the boat.

Remember Mike Huckabee’s big win in the 2008 Iowa GOP caucuses? The party’s eventual nominee, John McCain, won all of Iowa’s delegate votes at the national convention.

The history of the Iowa caucuses is actually a case study in the power of the media to shape – or warp, depending on your point of view – the nomination contest.

“The name of the presidential nominating game is perception, and the reality of the Iowa precinct caucuses has long been replaced by the media perception,” writes Drake University Professor Hugh Winebrenner. “It is not the caucus event per se but the media report of the event that shapes the presidential selection process.”

The Democrats, who stripped most nominating power from their party bosses after 1968, first realized Iowa’s power in 1972 when the press all but declared George McGovern the “winner” after his surprise second-place finish behind establishment favorite Ed Muskie. McGovern, a liberal anti-Vietnam War candidate, went on to win the nomination.

Four years later, a little known former Georgia governor rocketed onto the national stage by finishing second in Iowa behind an uncommitted delegate slate. Jimmy Carter eventually rolled all the way to the White House.

CNN.com: GOP presidential field still unsettled

In 1980, Iowa Republicans came up with the idea of a non-binding preference vote as a way to provide more concrete results to a media mob hungry for primary-style hard numbers to report. The elder Bush’s upset win over Ronald Reagan rattled the GOP race that year and eventually helped earn Bush the vice presidential slot.

In 1984, Gary Hart’s second-place Iowa finish beat expectations, set him up for a victory in New Hampshire, and established him as the main alternative to Walter Mondale. It also winnowed the field, effectively eliminating John Glenn after Glenn finished a disappointing fifth.

CNN.com: Did Gingrich push Medicare drug bill

In 2004, eventual Democratic nominee John Kerry jumped from third to first place in the national polls following his Iowa victory. John Edwards also surprised pundits with a strong second-place showing. Howard Dean and Dick Gephardt crippled each other with a barrage of negative ads.

Dean became best remembered for his infamous election night “scream,” which further damaged his insurgent campaign.

Four years ago, Barack Obama’s eight-point win in Iowa established him as a force to be reckoned with on the Democratic side. Hillary Clinton’s disappointing third place finish, meanwhile, undercut her early knockout strategy and set in motion a long nomination fight that her establishment campaign was ill-prepared to fight.

On the Republican side, McCain proved it’s possible to ignore Iowa and live to fight another day. The senator’s campaign set the media expectations bar low by making it clear he was focusing most of his attention on New Hampshire. McCain’s fourth place finish in Iowa proved to be irrelevant when he rolled to victory in the Granite State.

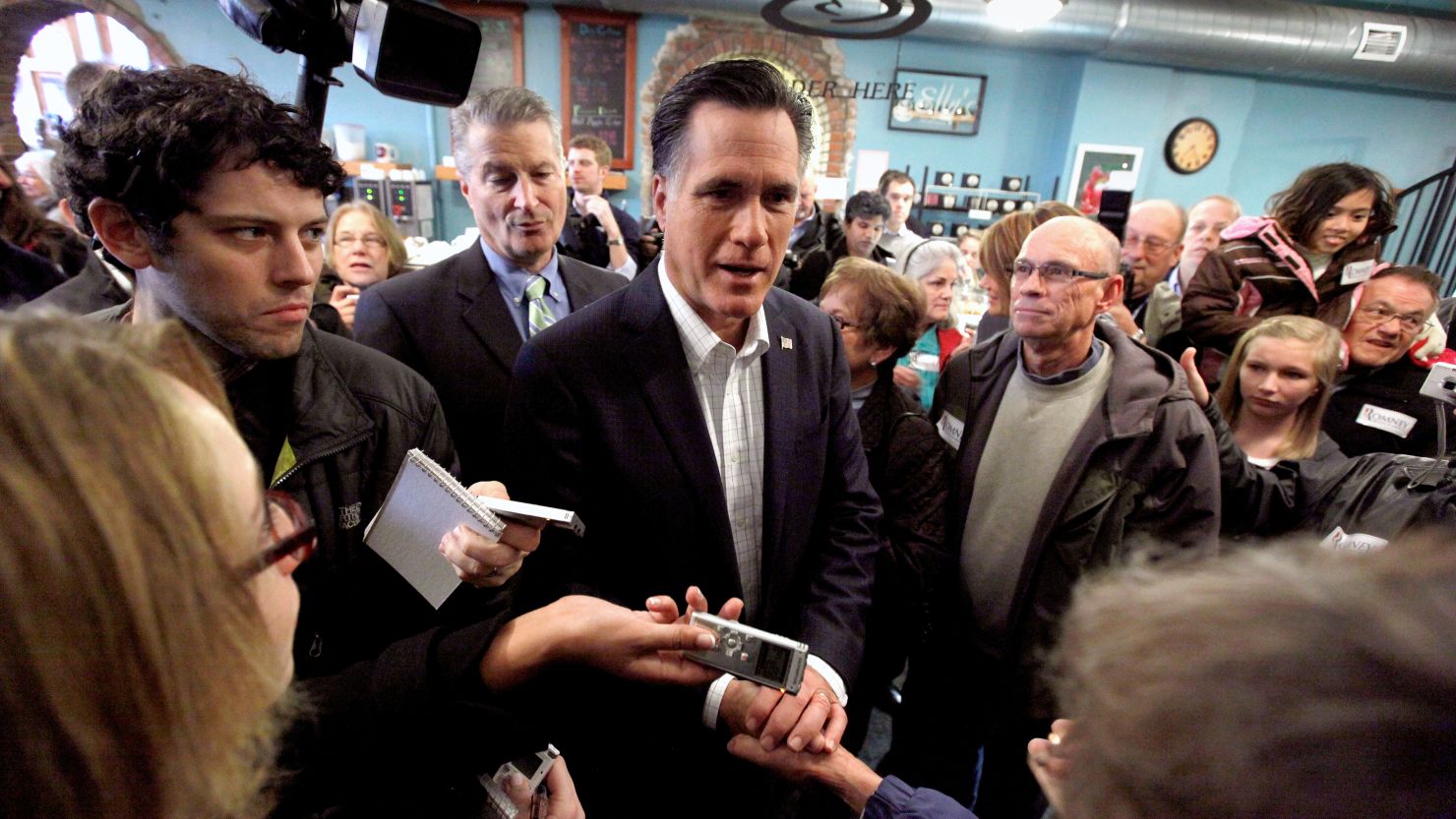

This time around, Mitt Romney’s camp has tried to keep media expectations low in Iowa – never an easy trick when you’re seen as the national frontrunner and are therefore expected to compete everywhere. A first-place Iowa finish for the former Massachusetts governor – overcoming regional, religious, and ideological obstacles – could set Romney up for a huge win the following week in neighboring New Hampshire. It could also signal an early end to the nomination fight.

Conversely, if Newt Gingrich hangs on for a first-place win in Iowa, the former speaker could potentially narrow Romney’s lead in New Hampshire and set the stage for a more protracted contest. Or maybe Rick Santorum’s investment in Iowa will reap a reward from the state’s social conservatives and earn the former Pennsylvania senator another look from activists in other parts of the country.

Perhaps the most intriguing possibility is a first-place finish by Ron Paul, a candidate with unorthodox GOP views on economic, defense, and social issues. A victory for the Texas congressman – who has a strong Iowa organization in place – would test the assumption that there’s a hard ceiling on his popular support. It could also help Romney by denying other candidates more favorable media attention.

Defenders of Iowa’s role in the nomination process fear a Paul win could potentially marginalize the state in the future by associating it with non-mainstream attitudes.

Iowa’s Republican governor, Terry Branstad, is already trying to finesse the significance of a Paul victory.

“It’s who comes in second and who comes in third as well as who comes in first,” Branstad recently told CNN. “And if somebody else does surprisingly well, it could well launch their campaign. It’s happened before. So you don’t necessarily have to win in Iowa, but you do need to be in the top three to be in contention going forward.”

Just remember: no matter who finishes first, second, or third in Iowa, nobody will be any closer to the magic 1,144 delegate mark at the end of the night. The January 3 caucuses are a media expectations game, the importance of which depends entirely on voter reactions to the headlines on January 4.

CNN’s Kevin Bohn, Keating Holland, Adam Levy, and Rob Yoon contributed to this report