As the returns rolled in on Super Tuesday, Joe Biden’s aides were flabbergasted.

Huddled at their headquarters in Philadelphia and snacking on candy carted in from the nearby “Nuts to You,” Biden’s campaign was braced for a long night of election results, according to a senior member of the campaign staff.

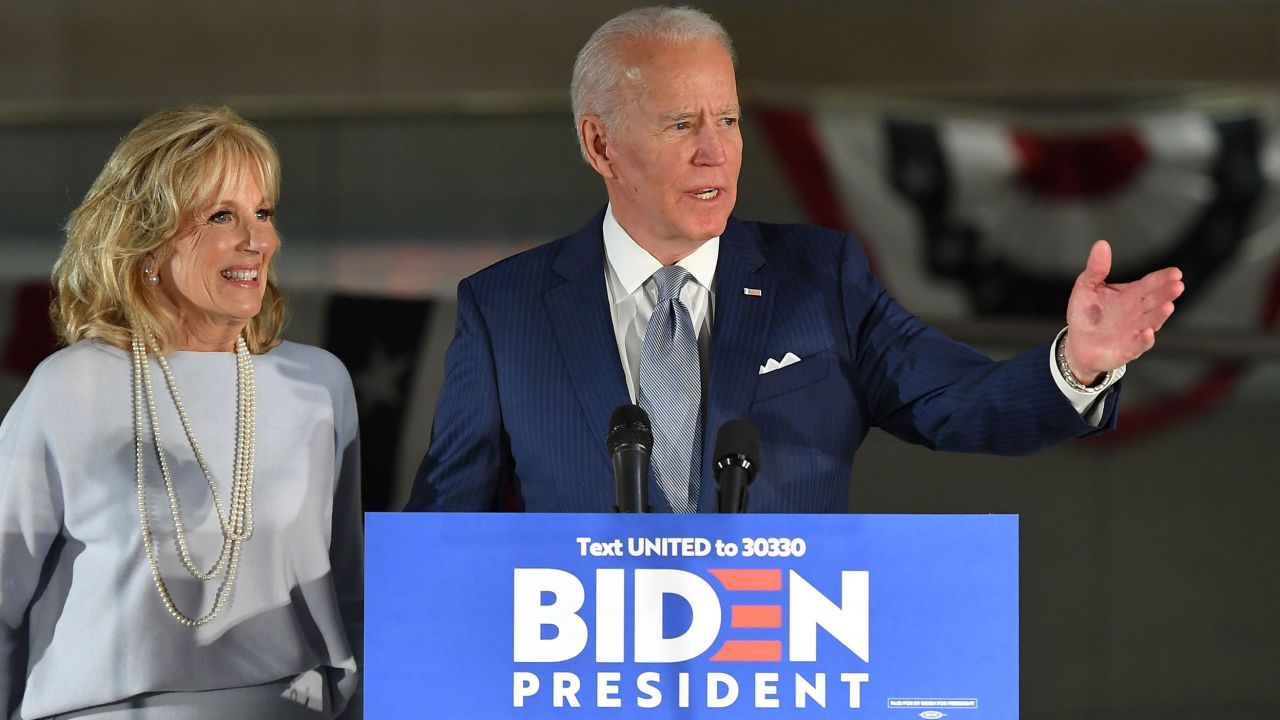

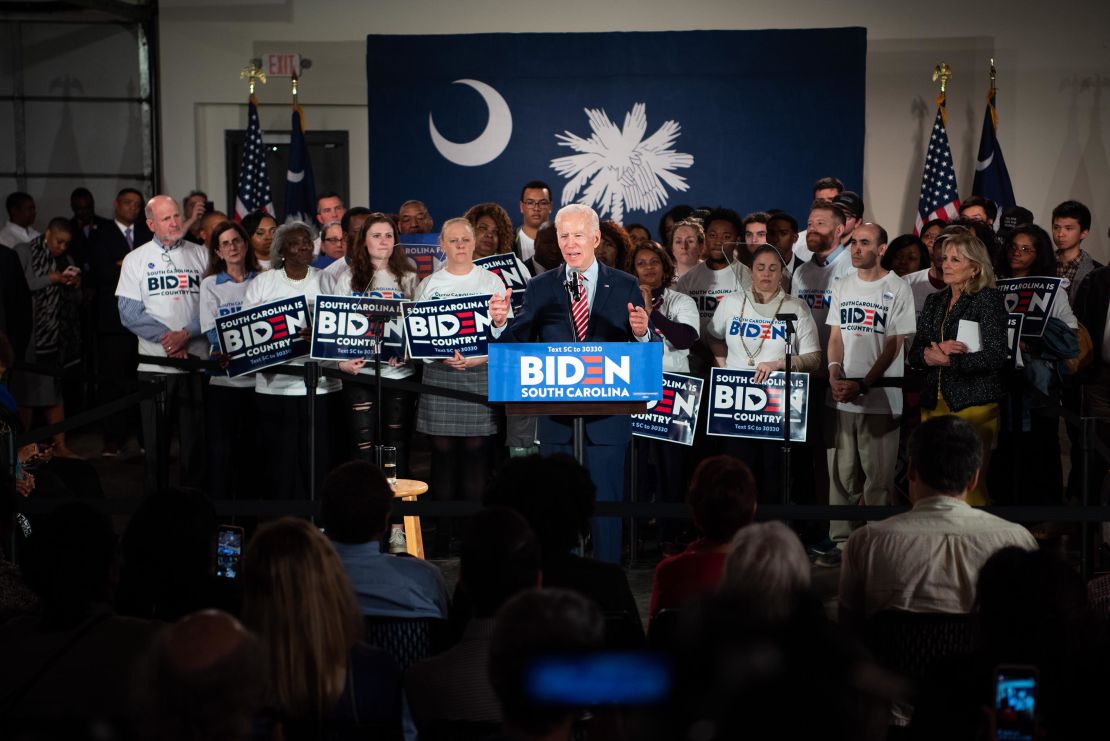

The team was cautiously optimistic after a resounding victory in South Carolina and a subsequent consolidation of the moderate wing of the party behind the former vice president. But their goals were still modest: Run up the margin as much as possible in most of the Southern states, and stay competitive in Texas and California.

Not only was the campaign meeting those goals, it was notching victories in places where resources had been withdrawn and field staff had been redeployed, like Massachusetts and Minnesota, and later Maine. There was no television in the conference room where Biden’s senior aides were holding the hourly meeting. But with each win, a loud cheer would erupt from the aides in the press area and at the front of the office, interrupting the meeting as everyone ran to the television screens to catch the latest victory.

Visit CNN’s Election Center for full coverage of the 2020 race

Just a few days earlier, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders was the race’s undisputed front-runner. Biden’s campaign appeared ill-equipped to pull off the comeback necessary to win. The fractured field of six top candidates seemed poised to split delegates on Super Tuesday, setting up the possibility of a contested convention.

But during the week and a half between the morning of South Carolina’s primary and this past Tuesday’s elections, three candidates got out of the race and endorsed Biden, and the former vice president racked up victories and delegates in 15 states to become a strong favorite for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Sanders has insisted that he is not leaving the race, but as the pair head into Sunday’s debate, the reversal of their fortunes could not be starker. Conversations with more than a dozen Democratic operatives and aides to Sanders and Biden offers a window into how the campaigns experienced the dramatic re-shaping of the 2020 race and how that transformation sets the stage for the contest’s next chapter.

The elements of Biden’s comeback during that 10-day span clicked into place. His aides had feared he would not be able to recover from a third or fourth place finish in Nevada. But his second-place finish in Nevada cleared the way for South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn’s pivotal endorsement.

Black voters – the historical arbiters of Democratic contests – coalesced behind Biden in virtual lockstep in South Carolina and later several more Southern states, even as Sanders continued to win young voters and Latinos. One-time rivals Amy Klobuchar, Pete Buttigieg and Beto O’Rourke all stepped forward in the 48-hour period that followed the Palmetto State primary to anoint Biden as the best candidate to confront Trump.

The speed of the consolidation of the moderate wing around Biden stunned the entire political universe, including the Sanders team.

Sanders’ aides had run a formidable campaign that carried a candidate who was at one time in fourth place in the polls – a candidate who had suffered a heart attack on the trail – to victories in New Hampshire and Nevada, and a near victory in Iowa.

Before Klobuchar and Buttigieg exited the race, Sanders advisers believed they were well positioned for Super Tuesday wins in Massachusetts, Maine, Minnesota and even Texas, where Sanders had planted an early flag.

But the coalescence behind Biden was so fast and widespread, there wasn’t even enough time to shift plans or ad buys before Super Tuesday.

“It was as though people had been waiting for a sign and South Carolina was their sign,” said Anita Dunn, a senior adviser to the former vice president’s campaign. “They liked Biden. They thought he could be president – that he was qualified to be president, and they just needed some piece of evidence to tell them that he was electorally strong and could build the kind of coalition to take on Trump, and they felt they got it in South Carolina.”

Setting the stage for the comeback

A mere two weeks earlier within the Democratic establishment, the question was not whether Sanders could get the nomination, but rather whether anyone could stop him.

The Sanders campaign was so bullish about their prospects that they ramped up their efforts in South Carolina – Biden’s firewall – placing a late $500,000 ad buy in South Carolina with the hope they could keep the race close, with a high single-digit margin.

Up until that point within a party scarred by the memory of Clinton’s defeat in 2016, most leaders had taken pains to show their neutrality from the sidelines.

But now Biden was dangling after his fourth-place finish in Iowa and fifth-place finish in New Hampshire, hanging his chances of a comeback on a distant second-place finish in Nevada.

With Biden’s lead shrinking in South Carolina, the campaign dispatched Symone Sanders to join South Carolina state director Kendall Corley to spend the two and a half weeks between New Hampshire and South Carolina in the Palmetto State – traveling the state, ramping up the field organization, managing surrogates to hold it together until Biden arrived.

Then a few days before the primary Clyburn stepped into the arena. “I know Joe. We know Joe. But most importantly, Joe knows us,” the venerable South Carolina lawmaker said as Biden stood beside him.

Clyburn set the tone for the two weeks to follow by centering on the electability question, stating that he was fearful about the future for his daughters and grandchildren under Trump: “It is time for us to restore this country’s dignity, this country’s respect,” he said, stating no one was better suited to do that than Biden.

During that week of the Clyburn endorsement and the South Carolina primary, unsettled Democrats were also watching a split screen as the current commander-in-chief begin bumbling his way through the coronavirus response, claiming it was “a problem that’s going to go away” and tweeting that the stock market was looking good to him.

On the same day that Clyburn endorsed Biden, President Trump returned from India to conduct a disastrous coronavirus press conference laced with misleading claims. Trump said “the risk to the American people remains very low” and made the now laughable assertion that “we’re going to be pretty soon at only five people” with the coronavirus. “We could be at just one or two people over the next short period of time,” Trump said.

Democratic voters felt increasingly uneasy about the odds that Sanders, with his calls for dramatic structural change in government and an overhaul of the nation’s health care system, could build a winning coalition for November. Those who had shopped around for months looking at other candidates decided it was now no time to gamble.

“Trump being in the White House, Bernie emerging as the frontrunner, and then the coronavirus all together—those were three different forms of fear for some Democrats,” said Paul Begala, the longtime Democratic strategist who helped engineer Bill Clinton’s “comeback kid” narrative in 1992. “My friends who are investors say when there’s a crisis there’s ‘a flight to quality’… In politics, I think Joe was the flight to quality. It was just like, ‘Well, you know, we’re not going to wrong with him.’”

Biden’s first victory

Biden had seen his share of election nights throughout five decades of running for office, but he had never encountered one like that last Saturday in February when the networks announced he was the winner on the presidential ballot in South Carolina at 7 o’clock when the polls closed.

As he reveled in his triumph that night, Biden received a congratulatory call from former President Barack Obama, praising him for his decisive win that would revive his quest to win the presidency.

It was not an endorsement call from Obama. The two men had discussed this several times before, with Obama had long insisted that putting his hand on the scales of the 2020 race would only backfire. On that night, an endorsement wasn’t discussed at all.

But, less than 48 hours later, Biden was basking in the praise of his two rivals, Buttigieg and Klobuchar, and O’Rourke, the former Texas congressman who had dropped out of the race in 2019.

Elizabeth Warren had knocked off Michael Bloomberg in the two previous debates, making it impossible for the New York Mayor to emerge as the Biden alternative. Now the race looked like a binary choice between Biden and Sanders, and the endorsements from party leaders flooded in as voters began to view the contest differently.

It was that period – from Sunday morning to Monday evening – that Biden’s advisers now believe were the most critical hours in his effort to make Super Tuesday truly live up to its billing. While Biden’s positive attributes and deep experience played a pivotal role in bringing his former rivals aboard, one top aide conceded that someone else was a bigger motivating factor.

“President Trump is the driving factor here,” the longtime aide said, speaking on condition of anonymity to reveal internal discussions. “If he wasn’t sitting in the White House, this would still be a wide-open race.”

Older voters, rather than the younger voters Sanders was counting on, mobilized and turned out in greater numbers at the polls.

The following week, in a stark contrast with 2016, working class voters split in key states like Michigan, giving the win to their longtime ally, “blue-collar Joe.”

And as a global pandemic swept the globe, more voters – particularly newly empowered suburban voters who turned the tables in 2018 – decided they would be in safer hands with Biden, both to confront crisis and battle Trump.

“When it’s a choice between Sanders and Biden, if you care about defeating Trump, you’re going to be with Biden,” said Mark Mellman, a longtime Democratic pollster who helped craft one of the early anti-Sanders for the pro-Israel super PAC known as Democratic Majority for Israel. “More than that, there was a general consensus among elected officials that having Sanders at the top of the ticket would prove a real danger to House members and Senators to candidates in competitive races.”

Sanders team goes all in on Michigan

The Sanders team never pursued endorsements in the way that Biden did. Sanders’ message was that he was taking on the Democratic establishment, not trying to be a part of it. But the flood of endorsements paid off for Biden on Super Tuesday, by giving him a unexpected boost from earned media.

In the leadup to Super Tuesday, cable news coverage of the race had morphed into what Sanders supporters viewed as a three-day informercial about how Biden was unifying the party. Though Sanders was talking to Warren frequently by phone, the Massachusetts senator was not ready to endorse, another blow to his campaign at a critical time.

“There’s never been any sort of embrace from any sort of representative of the establishment wing of the party signaling that it’s OK to be for Bernie,” said Brian Fallon, a former adviser to Hillary Clinton. “So you could say, ‘Oh, (the Sanders campaign) should have done that in that week in between Nevada and South Carolina’; ‘They should’ve tried to signal that there’s a coalescing happening.’ But really you can’t pull that together in one week’s time.”

To cut his losses in the week between the two Super Tuesday contests, the Vermont senator canceled an event in Jackson, Mississippi, and hunkered down in Michigan, a state where he vanquished Hillary Clinton four years ago – hoping to replicate the win that had given his campaign a jolt of momentum in 2016 that allowed him to continue on.

But press coverage centered on the notion that he was abandoning the pursuit of black voters who dominated the Mississippi primary, an idea he rejected.

“Everybody knows that there are limited amounts of time; we did three rallies yesterday,” Sanders told CNN’s Jake Tapper during his Sunday appearance on “State of the Union.” “We are working as hard as we can. You have to adjust the schedule at every moment.”

Sanders conceded that Mississippi was going to be a tough state for him and touted his endorsement from Civil Rights leader Jesse Jackson, who he hoped would help him make inroads with black voters as they campaigned together across Michigan.

In the Midwest, he relentlessly made the argument that Biden would be the weaker opponent against Trump because of his past support for “disastrous trade agreements” like NAFTA.

“Going into Wisconsin, key battleground states—all states that have been devastated by these terrible trade agreements I fear very much if Joe is the candidate,” Sanders told Tapper, echoing the argument he was making at his events on the trail. “Believe me, Trump will and has already talked about Joe’s record on trade.”

“I believe that we are the strongest campaign to defeat Donald Trump, (a) because we have a grassroots movement that is unparalleled, (b), because we have a voting record that speaks to the needs of working families.”

Winning begets winning

But the campaign was faltering, partly because Sanders’ effort to expand the electorate and build a winning coalition by driving up turnout of independent voters and younger voters did not materialize on the first Super Tuesday or the second. Turnout was up, yet it was Biden who was putting together a broad coalition of older voters, suburban voters and blue-collar voters.

Still, during the week between the two big Super Tuesdays, the Biden campaign remained clear-eyed about the road ahead. They knew Michigan offered a potential lifeline to Sanders, who had invested far more time and money into the state.

The momentum that had carried Biden into the March 3 contests had been overtaken by the nation’s distraction with the coronavirus virus outbreak, depriving both campaigns of much of the daily coverage they needed to get their message out more broadly.

Going into the second round of Super Tuesday contests, with Michigan’s 125 delegates looming large, Sanders’ strength in 2016 and his come-from-behind-win over Clinton dominated much of the political discussion.

But it missed two important facts: Biden is far more beloved than Clinton and Trump is sitting in the Oval Office, serving as a daily – or hourly – motivator to Democrats.

“Joe Biden is in the race,” Michigan Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist told CNN when asked why he supported Sanders in 2016, but decided to endorse Biden this time. “Michigan is a state of consequence. A win here is going to make the difference in 2020.”

Ultimately in that second round of Super Tuesday contests, Sanders did not perform as well in areas where he beat Clinton in 2016. He no longer had the leverage of anti-Clinton sentiment in key working-class areas of states like Michigan. Biden ran up big margins in urban and suburban areas.

When Sanders emerged before the microphones midday Wednesday, he was unsparing of his own campaign’s failures. He would fight on, but he sounded more like an ideological warrior than an aggressive delegate seeker.

“We are losing the debate over electability,” Sanders said bluntly, tallying his losses in Mississippi, Missouri, Idaho and Michigan. “I cannot tell you how many people our campaign has spoken to, who have said, and I quote, ‘I like what your campaign stands for; I agree with what your campaign stands for, but I’m going to vote for Joe Biden, because I think Joe is the best candidate to defeat Donald Trump.’”

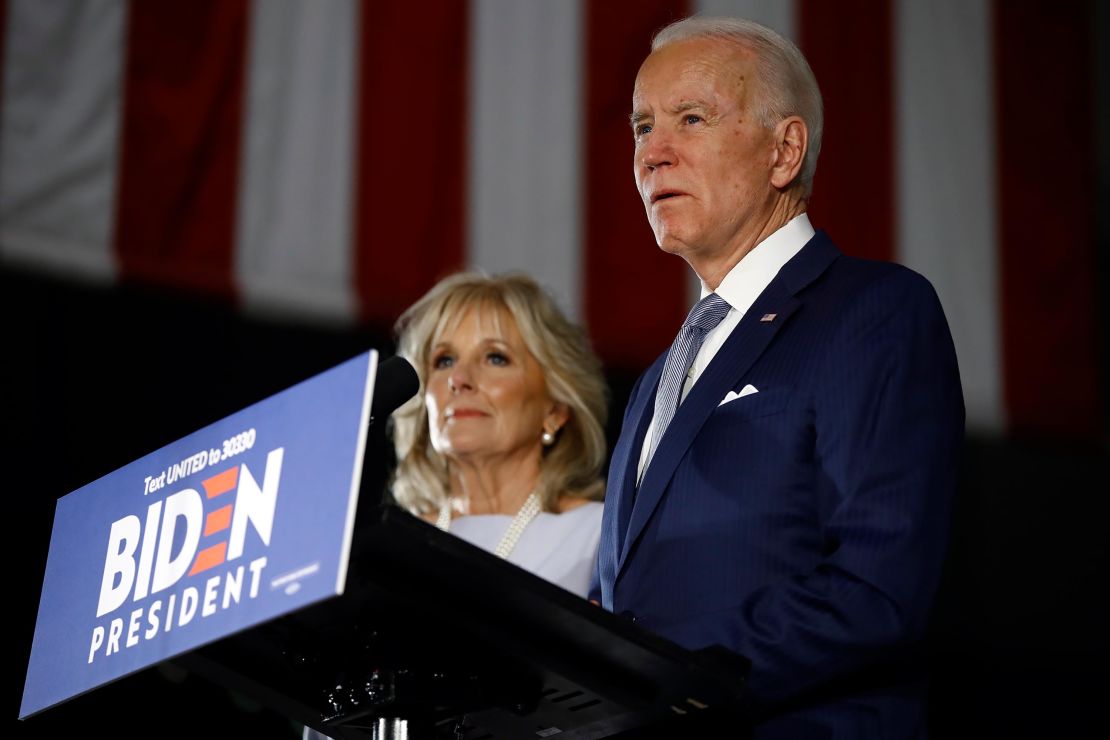

Biden’s unique connection to voters was a strength that also came to the forefront in those pivotal 10 days between South Carolina and the second Super Tuesday. Clyburn, Klobuchar, Buttigieg, O’Rourke and all the other leaders who campaigned for him reminded the American people of Biden’s chief strength: his deep empathy and connection with ordinary Americans.

It was a salient point during a period when President Trump cavalierly waved off concerns about the pandemic and later said he’d rather have thousands of people marooned offshore in a disease-infested cruise ship than to bring them on shore and have his number of infected people in America spike.

The contrast between Biden and Trump recalled one of the maxims of President Obama’s former strategist and CNN contributor David Axelrod, who says that when people fire a president they want “the remedy, not the replica.” Biden won every county in Michigan, the state where Sanders was hoping to revive his campaign.

Former Michigan Gov. Jennifer Granholm, a CNN contributor, said that voter connection to Biden was one of two central reasons Sanders could not replicate his 2016 strength.

“Trump is no longer a mere possibility as he was in 2016; he is a poisonous cancer that we urgently must remove from our body politic,” Granholm said, citing the first reason. “And second, I think the vote was more for Joe Biden than against Bernie Sanders.”

“People know Joe, his strengths and his challenges. They are willing to forgive his challenges because they know and trust him so much,” Granholm said. “They know he’s experienced horrific tragedy, been on the mat, but has gotten up. They feel he sees them because of his own tragedies. They know his heart, his intentions. And they feel protective of him in a way.”

Fresh off his string of victories – the biggest being Michigan, which Democrats lost to Trump in 2016 – Biden plans to swivel toward “a more of a presidential footing,” an adviser said Tuesday night, and start focusing on “the gravity of the moment.”

At the moment with officials warning against big events, concerns over the Coronavirus are also robbing Sanders of one of his biggest strengths: his ability to draw massive crowds of supporters – something Biden has always struggled to do.

As the two candidates prepare to debate Sunday night, one of the great unknowns about the closing chapter of the Democratic primary fight is whether scores of Sanders supporters will unify with Biden. Though some Sanders loyalists have told CNN in interviews in recent months that they will never support someone as “corporate” and deeply ingrained in the system as Biden, an air of practicality was clear during conversations with loyal Sanders supporters who came to see him in Michigan.

“We’re going to go as far as we can with the Bernie train,” said Beau Crnkovich, who stood alongside his mother at a Sanders rally on a sun-splashed Sunday rally in downtown Grand Rapids. “But if it comes down to Biden, I’ll definitely vote for Biden — for sure.”

CNN’s Dan Merica, Jeff Zeleny, Gregory Krieg and Jessica Dean contributed to this report.