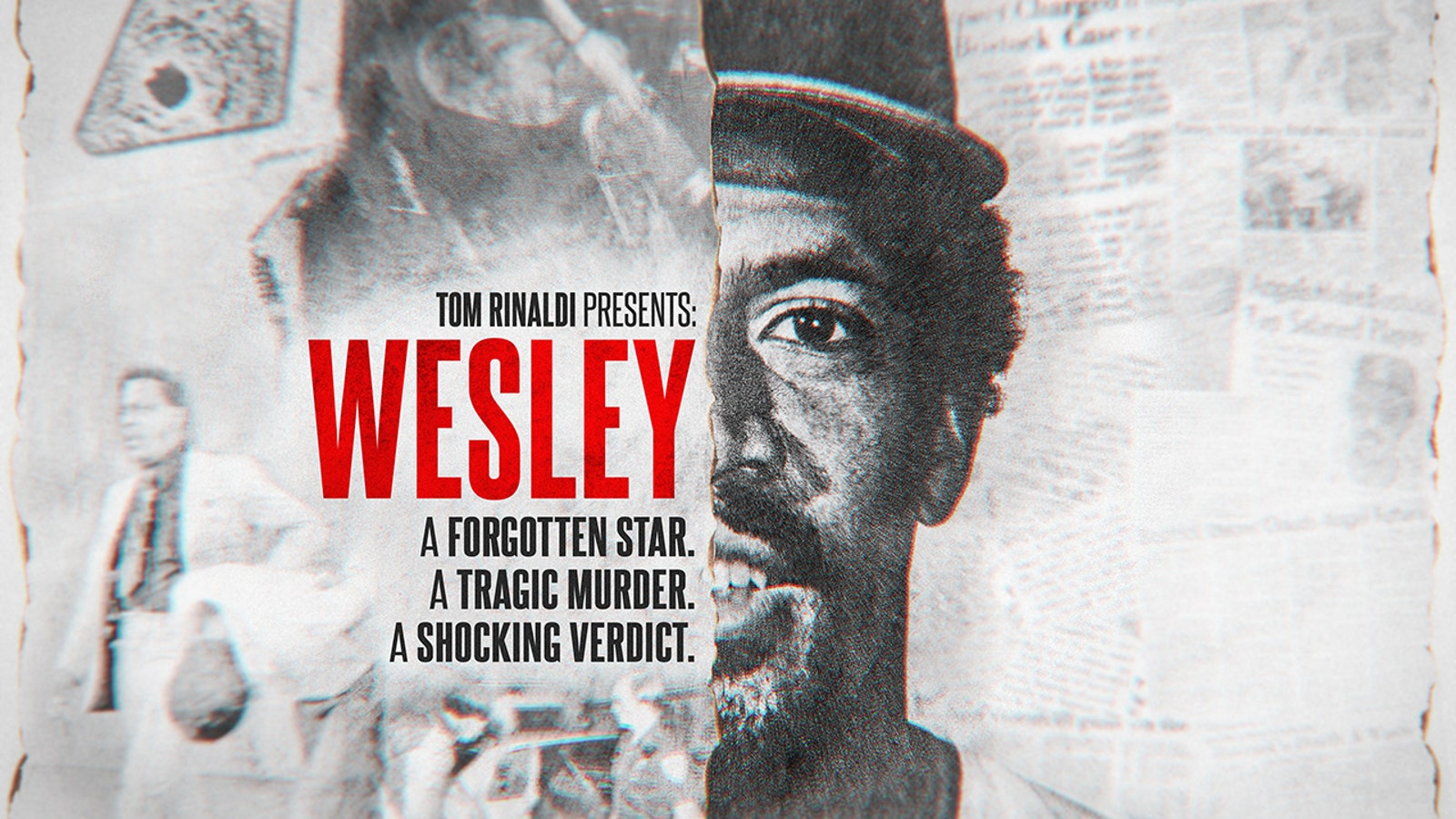

Tom Rinaldi's 'Wesley' examines life, legacy of Lyman Bostock Jr.

A budding baseball star. A philanthropist and social activist. A devoted husband.

The Lyman Bostock Jr. story can’t be told enough.

Not when his magnanimous life was cut short at 27 years old by an appalling murder followed by an unjust verdict.

Bostock's story is all covered in "Wesley," an eight-part, narrative-driven audio documentary chronicling the life, death and legacy of Bostock, who was gunned down in 1978 just as he was emerging into one of the best hitters in Major League Baseball.

The podcast series is a first for 17-time Emmy-winning storyteller Tom Rinaldi, who is executive producer, writer and host of the project. Rinaldi previously chronicled the tragic tale 14 years ago — Bostock remains the only player in MLB's roughly 150-year history to be murdered during a season — and it has weighed on him ever since.

Tom Rinaldi Presents: "Wesley"

Bostock was a beloved teammate with an infectious personality and a player whom Hall of Famers Rod Carew and George Brett have suggested would have vied for 3,000 hits had he played a full career.

"All things that ended at the end of his fourth season, through no fault of his own," Rinaldi lamented, before reminding that Bostock’s impact extended far beyond baseball. "There’s so much more in terms of depth and texture to Lyman's life that we weren't able to even begin to cover in the limits of the (original) television story."

That includes perspective from Bostock’s widow, Yuovene Whistler, who bravely revisited the trauma from her life to honor her late husband’s inspiring and tragic story. She is, as Rinaldi puts it, "the emotional ballast" of the podcast series.

"Someone who lost her husband in the earliest stages of their marriage, never had an opportunity to have a family together with him," Rinaldi said. "She did remarry, have a daughter, get divorced and build a remarkable life. She's an incredible portrait of strength. The ability to let people know about Lyman's journey and what he stood for, his tremendous job as an advocate in the late 1960s, for social justice and equality, the risks he took in terms of his own baseball career, to stand up for the principles he believed in.

"What a pioneer he was, what a harbinger he was of things to come — player movement, player advocacy, the power of an athlete's voice, all those things."

Well before Bostock reached the majors, he was fighting his way through a bigger game. It was the fall of 1968, a time of serious unrest across the nation and the globe, and the Los Angeles native was a freshman at San Fernando Valley State College (now Cal State Northridge). In response to a football coach kicking one of his players, Bostock joined a non-violent student protest at the university's administration building, which resulted in a remarkable set of charges, including felonies, and eventually jail time.

His involvement ultimately would keep him off the diamond for two years. The sabbatical didn’t erode his skills, however. Bostock, the estranged son of a Negro Leagues player, would be drafted before making his college baseball debut and then again after two decorated seasons.

"As Lyman says [of his father], 'He spent time teaching and helping Willie Mays much more than he ever helped me,’" Rinaldi said.

Like his father, the younger Bostock was a sensational left-handed contact hitter but with some decent pop. After raking for three years in the minors, Bostock was called up by the Minnesota Twins in 1975 and hit .282 as a rookie.

The lanky 6-foot-1 outfielder hit .323 the next season and .336 in Year 3, second only to teammate Carew in the American League. Bostock also registered 62 extra-base hits while slugging .508.

He became a coveted free agent and jumped at the opportunity to return home, signing a lucrative six-year contract with the California Angels. One of his first major purchases was rebuilding a church in Birmingham, Alabama, where he was born.

After batting .150 in the first month with his new team, Bostock offered to return his April salary to the club. When the Angels declined, Bostock donated the money to charity. He quickly turned things around and was hitting .296 on the season following a September afternoon game in Chicago.

That evening, while riding as a passenger along with an old friend and her sister in his uncle’s vehicle in nearby Gary, Indiana, Bostock was shot and killed by Leonard Smith. The two men had never met, but Smith later claimed he mistakenly believed Bostock was having an affair with his estranged wife, who was in the car. Smith was eventually found not guilty by reason of insanity and spent seven months at Logansport State Hospital before being released. He was never arrested nor convicted of another crime.

In a 2008 feature for ESPN’s "Outside the Lines," Rinaldi tracked down an elderly Smith outside his apartment building and attempted to ask him about what happened on the fateful night of Sept. 23, 1978. Smith, clearly struggling with his health, refused to comment during a brief exchange. He died of natural causes two years later, having never publicly spoken on the matter.

That part of the story will forever remain incomplete. Rinaldi’s meeting with Smith left him feeling similarly.

"There's a deep regret, one of the bigger regrets of my career, attached to a really important part of reporting that story — our encounter with the man that killed Lyman, and in my view, how I mishandled and botched that encounter," Rinaldi said.

"It revolves around the following question, which doesn't really have an answer, but has echoed in me: What is the value of posing a question, whether it ever receives an answer? Is there a value in knowing that a subject heard it, faced it? In essence, in your reporting, are you also a proxy for the family? Are you serving the audience? Are you also trying to serve your own natural curiosity? Even if the odds are long that you're going to get an answer. And the fact that many of those questions, ultimately, I did not ask, I failed to present to Leonard Smith in what turned out to be the only handful of minutes I ever got with him. That was a fail, that was a failure.

"I think I was unprepared for what I encountered in terms of Leonard’s physical appearance, in what time had done to him. Perhaps a part of me had created him in my mind to be a certain sort of man and character. And when he emerged from his car outside this three-story, brown tenement building, six and a half blocks from the place where he had murdered this great ballplayer, he looked nothing like the man I had imagined him to be. And my inability to adjust to the man who stepped out of that car and the person I saw in real time, that's what bothered me."

Rinaldi’s original piece on Bostock, accompanied by a brilliant feature from Jeff Pearlman, is one of few in-depth looks at this saga. In the immediate aftermath of Bostock’s death, the Gary Police Department received phone calls from reporters as far away as England, Brazil and Japan. But less than a week later, the death of Pope John Paul I dominated news coverage around the world. Over time, perhaps because Bostock didn’t win a batting title or make an All-Star team in his four seasons, his story seems to have slipped through the cracks.

The first two episodes of "Wesley" were released Monday. The remaining six are slated to drop in pairs over the following three Mondays.

"I hope people learn to appreciate Lyman Bostock, not only the greatness of his career, and what was lost, but the enormous potential for generosity and social change that he very well could have been at the forefront of, if it hadn't been for one single shotgun blast," Rinaldi said.

"I hope people want to explore his legacy in greater depth, and I hope that he's given his due as a great player on the field and a great person off it."