August is coming. Prepare for climate calamity

This is the July 28, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Lake Siskiyou is beautiful this time of year.

About 200 miles north of Sacramento, the artificial reservoir — formed by a dam on the Sacramento River — is ringed by quiet beaches that offer a cool respite from triple-digit heat. The views of Mt. Shasta are spectacular. When I visited last week, I saw double-crested cormorants, ospreys and great blue herons soaring over the water and ducklings swimming with their mother.

It’s a great spot to take a few days off from work. It’s also not immune to the climate challenges confronting California and the American West as we enter August — a crucial month for water supplies, wildfires, extreme heat and possible power shortages.

I’m not trying to be a downer. As I’ve written again and again, there’s a lot that can be done to stem the climate crisis.

But the next month could offer a nasty reminder of why climate action is so badly needed.

Let’s start with the electric grid. It was two years ago this August that parts of the Golden State suffered rolling blackouts — and we could be in store for more. Officials have warned of “a high degree of vulnerability” this summer as rising temperatures drive up air conditioning demand. The risk is especially bad on August and September evenings, after solar panels stop generating.

I asked Neil Millar, a vice president at the California Independent System Operator, about the odds of additional power shortfalls this summer. Not surprisingly, he wasn’t thrilled about the question, telling me it was like asking “how bad bad luck could get.”

“We’ve been in unprecedented times,” he said.

Overall, Millar was optimistic. He said the state has added thousands of megawatts of batteries that can bank solar power for after dark, and has taken steps to secure other energy supplies — some of them polluting — that can keep the lights on in a pinch, even as they fuel the global warming that’s gotten us into this mess. A bunch of solar-plus-storage projects that officials feared would be delayed by supply-chain slowdowns or other economic disruptions ended up plugging into the grid on schedule.

But the Independent System Operator can’t guarantee the lights will stay on, especially if the weather gets crazy.

“We’re as well positioned as we could have hoped to be,” Millar said.

This isn’t just a California concern. Across the country, the risk of blackouts is frighteningly high as rising temperatures strain electric grids and coal and nuclear power plants shut down, as Alexander C. Kaufman reports in a detailed story for HuffPost.

Another part of the problem: Intense drought means there’s less water behind dams to spin turbines and generate hydropower. Just look at my colleague Myung J. Chun’s dramatic photos of Shasta Lake, where water levels fell to 38% of capacity last week.

California would resort to intentional outages only to stave off a bigger electric-grid collapse. But shutting off anyone’s power during a heat wave is painful, and potentially lethal. As The Times has reported, extreme heat kills more Californians than officials have acknowledged, and global warming is making things worse — especially for people who can’t afford air conditioning.

Government agencies are trying to protect the most vulnerable. The Biden administration this week launched heat.gov to share tips on keeping cool and other information to help local officials deal with heat, as Lisa Friedman reports for the New York Times. Closer to home, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power is designing a program that would help low-income and elderly customers — and people who depend on electricity for medical equipment — purchase air conditioning units at a low cost.

“Lives are at stake. Los Angeles residents’ health is at stake,” DWP board President Cynthia McClain-Hill said at Tuesday’s board of commissioners meeting. “That means people we know. It means members of our families, and our neighbors.”

None of those steps will eliminate the risks of heat illness or death. But they can definitely help — especially with Northern California in the grips of a scorching heat wave, and with the hottest part of the year yet to come for coastal Southern California.

Compared with extreme heat — which we can expect to get worse just about every year — wildfire is more of a wild card. So far in 2022, just 53,000 acres have burned in California — far below the five-year average of 415,000 acres by this point in July.

But we’re now entering one of the most dangerous times of year for fire activity, as heat dries out the already parched landscape. The Oak fire has quickly become the state’s largest blaze of 2022 since igniting Friday, burning more than 18,000 acres near Yosemite National Park and destroying 25 homes. Thousands of people have been forced to evacuate, with one resident of the Sierra Nevada foothills town of Midpines telling my colleagues that as the fire blew up, “it looked like Godzilla over my house.”

Eighteen thousand acres isn’t much compared with the record-breaking million acres consumed by 2020’s August Complex fire — or last year’s Dixie fire, which chewed through nearly as much ground. But the Oak fire would have been considered a big one just a few decades ago, according to UC Merced climatologist John Abatzoglou. And it could be a prelude to the rest of the year.

“There’s a lot more of the fire season yet to go, and things are really crispy out there,” Abatzoglou said.

When I asked Abatzoglou for his top three wildfire solutions, two of his answers involved more fire: setting “prescribed burns” to clear out vegetation in forests that have grown much too dense after a century of overly aggressive fire suppression, and allowing blazes in remote areas far from homes to burn themselves out — a strategy known as “managed fire.” He’d also like to see more robust funding for people to harden their homes against flames, and to clear excess vegetation from around their properties.

What about reducing climate pollution? It needs to happen, Abatzoglou said, but it’s not an immediate fire solution.

“Even though I’m a climate person, I know we’re not going to slow this down in the next 20 years too much,” he said.

As if wildfires weren’t scary enough on their own, they can also exacerbate power-grid problems. Utility companies sometimes shut off electricity during high winds to stop their electric lines from sparking fires. Last summer, smoke from the Bootleg fire in southern Oregon knocked out several lines that bring power to California, nearly leading to rolling blackouts here.

Then there’s the drought situation. If you haven’t heard, it’s bad — and August could bring more unwelcome news.

In the next few weeks, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation will issue its latest forecast for water levels at the American West’s two largest reservoirs: Lake Mead and Lake Powell, which help supply tens of millions of people and millions of acres of farmland, from Los Angeles to Phoenix to Salt Lake City. The August forecast typically determines whether California, Arizona, Nevada and Mexico will see their Colorado River water deliveries reduced, as they were following last August’s first-ever shortage declaration.

Next month’s reservoir forecast will be grim — but that’s almost beside the point, says John Fleck, a Colorado River expert and writer in residence at the University of New Mexico School of Law’s Utton Transboundary Resources Center. That’s because in mid-June, the Bureau of Reclamation gave the seven Colorado River states 60 days to develop a plan to reduce water use dramatically — by 2 million to 4 million acre-feet next year. If they don’t make it happen, the federal agency could order draconian cutbacks.

Everyone will need to use less water, Fleck told me. But he suggested it will be especially important for wealthy cities to find ways to compensate rural, agriculture-dependent communities such as Blythe and the Imperial Valley for cutting back.

“Climate change is coming in and taking their water. But we need to help them,” Fleck said.

So far, there are no real public signs a robust plan will come together. The river’s Upper Basin states — Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming — have declined to promise anything substantial, saying the onus should be on the Lower Basin states, per Luke Runyon at KUNC. And it’s unclear if California and the other Lower Basin states are having much success in agreeing on cutbacks.

Fleck said the most “politically expedient” path forward — especially in Arizona, where water cuts are deeply unpopular — might be to punt to the federal government. He thinks that would be an unfortunate outcome, embracing conflict over cooperation.

“We’ve got to own up and take responsibility for the fact that this is all of our faults as water users,” Fleck said.

Meanwhile, water levels continue to fall. Lake Mead is at a record-low 27% of capacity — and if the numbers don’t do it for you, check out these wild NASA satellite photos showing how the desert reservoir has shrunk. Human remains were found on a Lake Mead beach this week as the water receded — the third time that’s happened since May, my colleague Christian Martinez reports.

Just like with wildfire, slashing planet-warming emissions is not an immediate solution to the long-term drying trend in the American West. But without serious climate action, there’s also no way to avoid even worse catastrophe down the road.

It’s still possible the federal government will get its act together. Sen. Joe Manchin III of West Virginia — a Democrat who for months has blocked President Biden’s climate proposals — abruptly announced late Wednesday he’d struck a deal to support a sweeping bill focused on energy and climate, among other issues. The details were still coming into focus as of this writing, but here’s an early summary from my colleague Jennifer Haberkorn, who writes that the bill includes $369 billion for energy security and climate policies.

In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom is trying to step up on climate, even as he supports the short-term use of fossil fuels to bolster power supplies. He sent a letter to state regulators last week asking them to plan for a gargantuan 20 gigawatts of offshore wind power by 2045, and setting a target of 7 million “climate-ready and climate-friendly homes” by 2035. That could mean homes equipped with electric heat pumps instead of polluting gas furnaces, and retrofitted to keep people cool during heat waves.

Newsom also asked state agencies to plan for a clean energy transition that includes no new natural gas plants — a big win for climate activists. The California Air Resources Board has recently projected a need for 10 gigawatts of new gas plants to help keep the lights on when solar panels and wind turbines aren’t generating, and to support electric-vehicle charging.

“This isn’t revolution. This should be the expectation,” said Alexandra Nagy, California director at the public affairs firm Sunstone Strategies, which works closely with environmental groups and has pushed Newsom to take bolder action on climate.

It was hard for me not to think about this stuff last week, even as I relaxed on the shore of Lake Siskiyou. Had drought reduced hydropower production at Box Canyon Dam, which I glimpsed while hiking around the reservoir? How much cooler would it be if the planet hadn’t already warmed up so much? Would I see more birds? Would there be more snowpack on Mt. Shasta?

I don’t have good answers to those questions. I do recommend the occasional vacation, though. We all deserve a break.

Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

California is making plans to rely on carbon capture — at least a little bit — to meet its climate goals. But environmental critics say the technology would extend the state’s reliance on fossil fuels and continue a harmful legacy of pollution in low-income neighborhoods, my colleague Tony Briscoe writes. The state’s Air Resources Board is gearing up to finalize its all-important climate “scoping plan” this fall, so look out for more news on this front. In another key political development, Gov. Gavin Newsom is opposing a Lyft-backed ballot measure that would tax multimillionaires and put the money toward electric car rebates and wildfire prevention, calling Proposition 30 “a special interest carve-out.” Details here from the Sacramento Bee’s Owen Tucker-Smith.

It took three years, but the Newsom administration has new details on a proposed delta tunnel to move Sacramento River water to Southern California and the San Joaquin Valley. The latest iteration of this massive infrastructure project — first proposed many decades ago — would skirt under the eastern edge of the ecologically fragile estuary where the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers meet, rather than under the delta’s heart, Dale Kasler and Ryan Sabalow report for the Sacramento Bee. But the project still has many critics, and it’s unclear whether the tunnel will ever get built. Construction wouldn’t start until 2028.

Reuters published a powerful investigation of the radioactive contamination from Santa Susana Field Lab just outside L.A. — and Boeing’s use of a “conservation easement,” which critics see as an increasingly common tool for companies to limit their toxic waste cleanup responsibility. Here’s the story from reporters Jaimi Dowdell and Andrea Januta. See also this Arizona Republic piece by Zayna Syed about the lack of funding for cleaning up hundreds of abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation, and this High Country News piece by Jonathan Thompson about oil companies evading cleanup obligations in New Mexico.

WATER AND WILDLIFE

One of Mexico’s wealthiest cities has so little water that many residents — especially the poor — get nothing when they turn on their taps. What’s happening in Monterrey is a warning for the Western U.S., my colleague Kate Linthicum writes. It’s a warning at least some places are taking seriously. California is finalizing rules for “direct potable reuse” — purifying wastewater and putting it right back into the tap — and L.A. could be the first city to actually do it, The Times’ Jaimie Ding reports. Las Vegas is limiting the size of new residential swimming pools, per Grace Da Rocha at the Las Vegas Sun. And many individuals continue to do their part — including one Pasadena resident embracing “hugelkultur” to reduce her water use, as Jeanette Marantos writes.

Could robots picking indoor crops keep food production humming even as rising temperatures, water shortages and chemical regulation slam traditional agriculture? Here’s the fascinating story by my colleague Sam Dean, focused on the California strawberry industry. I hadn’t realized 90% of the nation’s strawberries are grown along the California coast, which is pretty cool. In other agriculture news, ranchers say cattle grazing in the West is crucial for the health of the land — but there’s a lot of science showing otherwise, including serious climate damage. Thanks to Georgina Gustin at Inside Climate News for the story.

How did California go from paying hunters to destroy mountain lions to spending millions protecting them? The Times’ Patt Morrison traced the history, from some ugly L.A. Times coverage a century ago, to the role of Ronald Reagan in reining in hunting, to the ballot measure that ultimately created funding to buy habitat for the majestic beasts. (Another mountain lion was killed on the 101 Freeway last week, marking four of them killed by cars in Southern California this year.) In other Western wildlife news, the International Union for Conservation of Nature has determined monarch butterflies are at risk of extinction — but the U.S. still hasn’t given the migrating insects endangered species protections. Details here from Christina Larson at the Associated Press.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

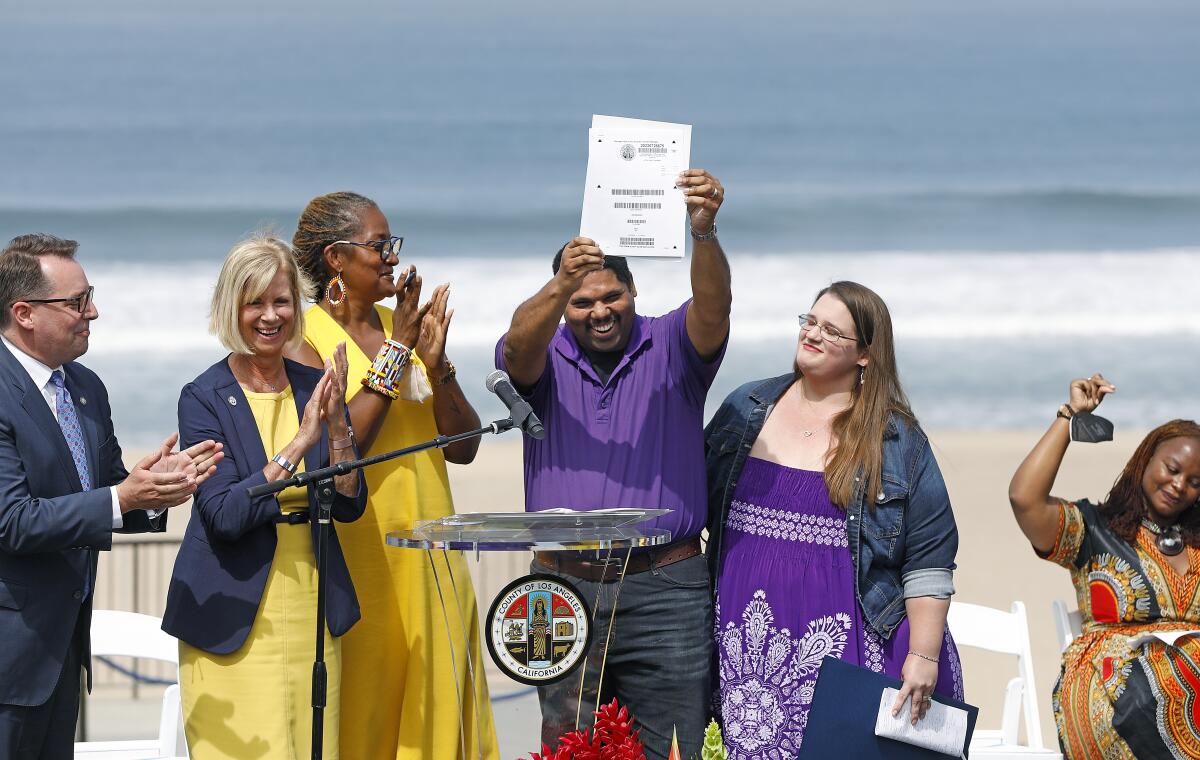

“We have set the precedent, and it is the pursuit of justice.” For the first time ever, government has returned land that was wrongfully taken from a Black family — and it’s right on the California coast. My colleague Rosanna Xia wrote about the heartfelt ceremony in which the Bruce family took ownership of Bruce’s Beach. “Today, we’re sending a message to every government in this nation confronted with the same challenge: This work is no longer unprecedented,” L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn said.

Nonprofit news outlet Floodlight and the Orlando Sentinel have several new entries in their eye-popping investigation into Florida Power & Light, a subsidiary of NextEra Energy, the nation’s largest power company. First, Floodlight’s Mario Alejandro Ariza and the Sentinel’s Annie Martin reported that operatives working for the Florida utility gained control over a political news website and influenced coverage to try to benefit the company. Next, the journalists revealed that NextEra consultant Matrix LLC — which has been described as “the closest thing Alabama politics has to a non-governmental secret agency” — has worked on campaigns not only for NextEra but also for power companies as far away as Arizona. (Floodlight’s Miranda Green also co-wrote that story.)

A bill sailing through the California Legislature would task state officials with estimating the carbon emissions intensity of oil tanked in from overseas. At least one climate-friendly lawmaker supports the legislation. But it’s also backed by the oil industry, and environmental critics suspect the data would be used to promote in-state drilling, Aaron Cantu reports for Capital & Main.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

Ford has signed a binding agreement to buy lithium for electric car batteries from the proposed Rhyolite Ridge mine in Nevada. It’s part of a growing effort by the U.S. auto industry to source lithium domestically, from spots such as northern Nevada and California’s Salton Sea, Reuters’ Ernest Scheyder reports — a priority for car companies in part due to forced-labor concerns at Chinese lithium mines. But the domestic lithium push faces a backlash from some conservationists. The Associated Press’ Scott Sonner wrote about the environmental challenges slowing down lithium mining and geothermal energy projects in Nevada.

In related news, Kansas is getting the largest economic development project in its history — a $4-billion Panasonic lithium-ion battery factory that will rival Tesla’s Nevada Gigafactory in scale. Here’s the story from Canary Media’s Shel Evergreen.

There’s still no word on when the California Public Utilities Commission might propose new rooftop solar incentive rates, six months after Newsom basically rejected its previous proposal. That didn’t stop protesters from gathering at Sempra Energy headquarters to voice their displeasure with the company, whose San Diego Gas & Electric subsidiary has pushed for lower incentives, as the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Rob Nikolewski reports. Stay tuned as I continue to track this story.

ONE MORE THING

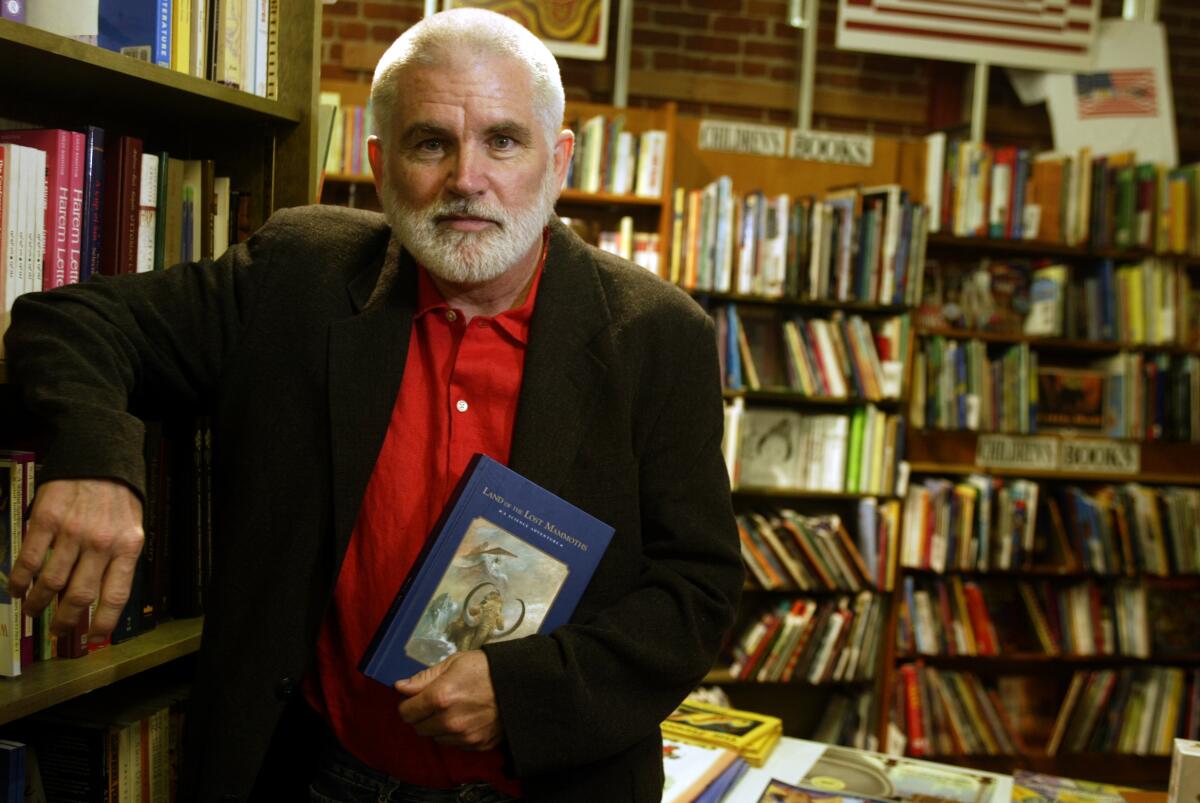

The writer Mike Davis is legendary for chronicling the story of Los Angeles, most notably in the 1990 book “City of Quartz.” He’s also known as a “prophet of doom.” He famously foretold environmental disaster in another tome, “Ecology of Fear.”

Now he’s dying of esophageal cancer — and as much as he sees climate nightmares on the horizon, he’s also got ideas for how people can demand change. As he told my colleague Sam Dean: “We’ve forgotten the use of disciplined, aggressive but nonviolent civil disobedience. Take climate change. We should be sitting in at the headquarters of every oil company every day of the week. You could easily put together a national campaign. You have tons of people who are willing to get arrested, who are so up to do it.”

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.