NASA starts designing futuristic space telescope to hunt for alien Earths

The Habitable Worlds Observatory mission is starting to take shape.

NASA's latest flagship telescope is still in its first year of science, but the agency isn't only hard at work building its successor — it's starting to plan that next mission's successor as well.

In November 2021, a decadal document produced by the U.S. National Academies of Sciences directed NASA's astrophysics division to concentrate its efforts on the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, currently targeting launch in the mid-2020s. But the report also nudged NASA to get a start on the subsequent flagship astrophysics mission, which it recommended be a space telescope observing in infrared, optical and ultraviolet light that could search for habitable exoplanets and signs of life on them.

Now, NASA has offered its first glimpse of what that mission will look like. For now, it will be known as the Habitable Worlds Observatory, Mark Clampin, the director of NASA's astrophysics division, said during a presentation on Monday (Jan. 9) at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society held this week in Seattle and online.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope's best images of all time (gallery)

First, despite the name and goal, NASA is considering the project an astrophysics mission, Clampin said. To meet its mission of searching for life, the Habitable Worlds Observatory will need to be a super-stable telescope equipped with a powerful coronograph, an instrument that allows scientists to study faint objects like rocky planets near bright objects like stars. But that's a powerful combination for astrophysicists as well.

"Even though you may at first blush look at it and say, 'Well, this is an exoplanet mission,' it's not; it's an observatory," Clampin said.

The National Academies of Sciences document, nicknamed the decadal survey, also noted that NASA should use small missions to develop X-ray and far-infrared observing technologies that can be used on two large space telescope missions that should later join the Habitable Worlds Observatory to bring more power to a wider range of wavelengths.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's clear that NASA doesn't want to see the construction of the Habitable Worlds Observatory turn out like that of the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb or JWST) did, blowing through both timelines and budgets with effects that rippled through agency projects. Clampin noted that the agency will be approaching the Habitable Worlds Observatory as if the spacecraft faced a strict launch window dictated by solar system dynamics, the way planetary science missions often do.

He said the approach should also keep the project's budget in line, and keep the agency moving toward the large X-ray and far-infrared missions as well. "The faster you get it done, the sooner you can also think about the next two great observatories," he said of the Habitable Worlds Observatory.

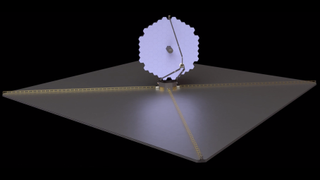

Fortunately, the new telescope will be starting on much firmer technological territory than JWST did: It will build directly on JWST's pioneering segmented mirror, as well as the powerful chronograph that will fly on the Roman Space Telescope, Clampin emphasized.

The new mission will also have a backup plan built in, he said. The Habitable Worlds Observatory, like JWST, will be perched 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth opposite the sun, at a spot known as Earth-sun Lagrange point 2 or L2. But unlike its neighbor, the future observatory will someday benefit from robotic upgrades.

"We're also going to plan this mission from day one to be serviceable," Clampin said. That decision will build on the success of the venerable Hubble Space Telescope, which was first rescued and then given powerful new instruments during five visits from astronauts, most recently in 2009. The approach will also make use of hefty commercial investments in robotic servicing, which made history in 2020 when a commercial satellite took over orbit maintenance for an aging internet satellite. (Hubble orbits just a few hundred miles above Earth, so it's relatively easy for astronauts to get to. Crewed servicing missions all the way out to L2 are not feasible at this point.)

"In 10, 15 years, there are going to be a lot of companies that can do very straightforward robotic servicing at L2," Clampin said. "It gives us flexibility, because it means we don't necessarily have to hit all of the science goals the first time."

NASA will turn to the commercial sector for a second key contribution as well, the launch vehicle. Taking that route should reduce the size and weight constraints the telescope will have to meet to get off the ground, Clampin said.

JWST's tense two-week unfolding sequence, with more than 300 potential mission-ending failure points to navigate, was implemented to fit the telescope's massive mirror and sunshield into the 15-foot-wide (4.5 m) fairing of its Ariane 5 rocket. But future rockets are being designed with much more cargo space. For example, Blue Origin's New Glenn rocket is designed to carry a 23-foot-wide (7 m) fairing and SpaceX's Starship will boast a 30-foot-wide (9 m) fairing, according to the companies.

"There are a number of commercial companies making very big fairings and launches now; we would be insane not to use them," Clampin said. "Big fairings on big rockets give you flexibility."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

-

elrayoex Does anyone else see an optical illusion (I think?) on the alien hunting telescope? Look at the image, look away for a moment, and then look back at it. Let me know if you detect anything unusual about the telescopeReply -

COLGeek Reply

Looks like an image redraw when scrolling the page.elrayoex said:Does anyone else see an optical illusion (I think?) on the alien hunting telescope? Look at the image, look away for a moment, and then look back at it. Let me know if you detect anything unusual about the telescope -

elrayoex It looks like the Purple (ish) thing is moving to me. Very subtle, but definitely there.......or is it really just me??Reply -

rod "First, despite the name and goal, NASA is considering the project an astrophysics mission, Clampin said. To meet its mission of searching for life, the Habitable Worlds Observatory will need to be a super-stable telescope equipped with a powerful coronograph, an instrument that allows scientists to study faint objects like rocky planets near bright objects like stars. But that's a powerful combination for astrophysicists as well."Reply

This should be challenging to accomplish and something if done. Consider that 1 arcsecond resolution at 100 pc = 100 au diameter. A habitable earth size or earth like planet will lie much closer to the host star than 100 au separation. -

sciencecompliance I wonder why the sun shield is so much bigger than Webb's relative to the size of the mirror. Is that to give it a wider available field of view (can slew at larger angles)?Reply

Also, while this is exciting that they're working on the next generation of space telescopes, I'd really like to know if progress is being made on a mission to get (a) telescope(s) out to the solar gravitational focus. That kind of mission would be designed to see only one star system, but it sounds like the resolution possible would be truly insane. A recent PBS Spacetime video covered this and said it might be possible to get something on the order of 25 km per pixel images of an exoplanet's surface. As a point of reference, this is better resolution than the Earth as seen in the famous "Earthrise" image. -

billslugg The Sun's gravitational focus is at a minimum of 550 AU, this light is bent inside the corona and would be very hazy, much farther is better.Reply

After 45 years, Voyager I is only 150 AU away. No one is interested in a project that would take 135 years to see results. This must wait for more advanced propulsion technologies which we don't have. We will probably have to master fusion first. -

sciencecompliance Replybillslugg said:This must wait for more advanced propulsion technologies which we don't have. We will probably have to master fusion first.

The idea discussed in the PBS Spacetime video would utilize a small spacecraft (or multiple spacecraft) propelled by a solar sail that would 'tack' in close to the sun and then "let 'er rip" once at about 1/4 the distance from the sun as Mercury. The top speed would be much faster than the Voyager probes. They discussed something on the order of 25 years to get out to the focus. I don't know much about the maturity of the technologies that would go into this, but the 135-year travel time is much longer than what the proposed concept is suggesting. -

billslugg I found this article which is even more pessimistic than I thought. The distance would have to be around 2,000 AU, not 450. Also once it got there, it would have to follow a 150,000 km ellipse in order to stay within the image as the purported planet orbited its star. Such a propulsion system would be very large and heavy, not amenable to a solar sail.Reply

I am sure they are looking at it, but with such high technological hurdles there probably is not going to be much in the way of resources put against it.

A Space Mission to the Gravitational Focus of the Sun | MIT Technology Review -

sciencecompliance Interesting. Sounds like this may not be possible for generations to come, if at all. The promise of what can be achieved is so tantalizing, though, and some of these problems do seem like they are surmountable with some clever tricks (provided the mission has ample funding for a swarm of spacecraft). Increasing pointing accuracy by a factor of 100 does seem like quite the challenge, as well as knowing the position of the planet to high enough accuracy, and of course getting out to 2,000 AU on a reasonable timescale.Reply