The Real Reason Young Adults Seem Slow to ‘Grow Up’

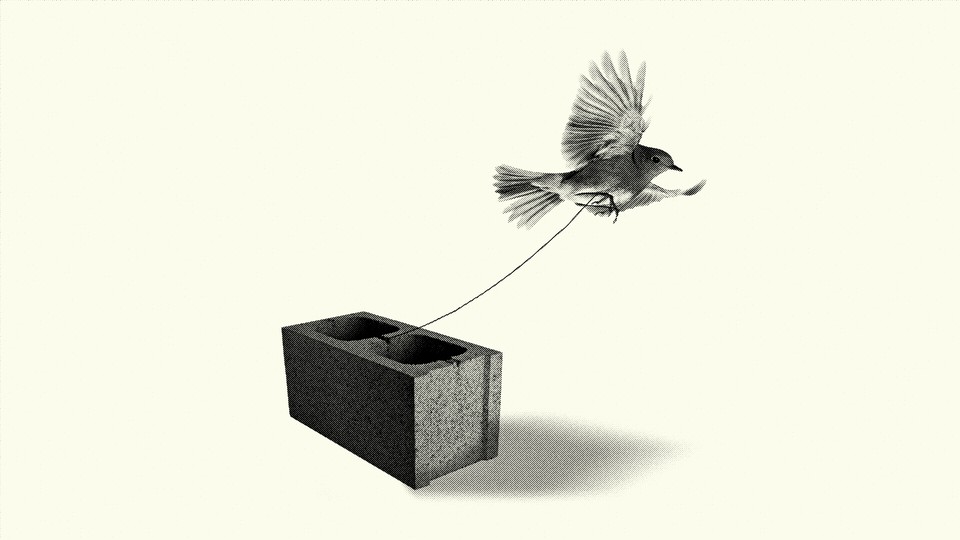

It’s not a new developmental stage; it’s the economy.

Every generation, it seems, bemoans the irresponsibility and self-indulgence of the one that follows. Even Socrates described the folly of youth in ancient Greece, lamenting: “Youth now love luxury. They have bad manners and contempt for authority.” However, in recent years, commentators have argued that something is distinctly stunted about the development of today’s young adults. Many have pointed to Millennials and Gen Zers as being uniquely resistant to “growing up.” Some theorists have even suggested that a new developmental stage is needed to account for the fact that youth today are taking longer to reach adulthood and are more reliant on their parents than generations past.

Yet nothing about delaying adulthood and extending adolescence is uniquely modern. Taking more time to come of age is not due to lack of stamina or motivation on the part of today’s youth, as the common narrative proclaims. Delayed adulthood is an expected response to the economic conditions shaping the period when young adults enter the workforce.

Five indicators are commonly understood as the markers of adulthood: finishing one’s education, leaving home, finding work, finding a life partner, and having children. Although many young adults reach the legal age of adulthood before they achieve these five markers, and others do not choose to reach them all, many still consider some combination of these benchmarks to define what it means to be an adult. Compared with the mid-20th century, young adults in the United States appear to be taking longer to reach these markers today. Fewer young-adult men ages 16 to 24 are settled into permanent jobs, and fewer men and women are married with children today than in the 1950s. Further, the median age at first marriage for men rose from 23 in 1950 to 30 by 2018. For women, the median age at first marriage rose from 20 to 28 over the same period. These mid-20th-century patterns are often used as the measuring stick against which young adults today are judged. Based on these data, young people today do seem unique in delaying adulthood. But this is only part of the picture.

Looking at a broader arc of history, across more than a century, a different pattern emerges. In the late 19th century, youth achieved the markers of adulthood at ages similar to youth today. Despite the fact that life expectancy was less than 50 years, in 1890 the median age at first marriage was 26 for men, though women still married relatively young, at a median age of 22. The number of young adults living with their parents over the years forms a U-shaped curve: In 1900, 41 percent of adults ages 18 to 29 lived with their parents, rising to 48 percent in the aftermath of the Great Depression. That number dipped to 29 percent in 1960 and then rose steadily again, reaching 47 percent in early 2020, just prior to the pandemic shutdowns. The evolution of the average age of childbearing shows similar parallels, taking a dip in the mid-20th century. Considering this longer time frame, it becomes clear that young adults in the 1950s were the outliers. Today’s youth reach the markers of adulthood on remarkably similar timelines to the youth of a century ago.

The sense of pressure and angst that many young adults feel about the future is also not unique to our time. In 2016, we discovered a forgotten archive of research, conducted from the 1950s to the 1970s, in the attic of an old building at Harvard University. This discovery included reel-to-reel tape recordings of college students who, at the end of each school year, had been asked just one open-ended question: “What stood out to you from the past year?” In hour-long reflections, they shared their struggles and triumphs, their worries and hopes. These recordings offered us an opportunity to listen to the voices of young adults describing the process of growing up while they were in the midst of the experience. We heard these students describe what it meant to become an adult in their contemporary context. The students’ concerns, anxieties, and goals seemed to transcend time and echo the voices of the students we study today.

The researchers who recorded these interviews made an assumption similar to what many people think today. Having previously conducted research with students in the ’50s, they sensed that something was different about coming of age in the 1960s, amid a cultural shift that marked a transformative moment in history. Yet what they found was that despite different historical contexts and increased demographic diversity in their later samples, students from the 1960s and ’70s reported having a very similar experience in transitioning to adulthood as those from the ’50s. Finding little value in the “null” research results, the researchers abandoned the study and packed it up into the attic, where it stayed for 50 years.

After we discovered this trove of data, we spent five years reanalyzing it, looking for differences and similarities in the coming-of-age experience across generations. The differences came only from anachronistic cultural or historical references, such as referring to President Richard Nixon or the Vietnam War when discussing politics. But these students shared core developmental experiences with young people today. On the old recordings, students described feeling overwhelmed because they did not know the best path forward or how to figure it out. They worried about getting meaningful jobs and about how to make high-stakes decisions when faced with numerous opportunities and trade-offs. They felt pressure from their parents to succeed academically and professionally. They felt pressure to not squander their opportunities. But they had a hard time finding support from others to help them navigate the new terrain of life after school. Consequently, many felt lost, paralyzed, and uncertain about the future.

In these recordings, we heard students describe wanting time: time to connect their purpose to a fulfilling career, and to catch their breath before plowing forward into the unrelenting responsibility of adulthood. In short, these young adults were seeking to delay reaching adulthood much like many Millennials and Gen Zers do today. The parallels we discovered helped us understand why and when youth need more time to transition to adulthood.

Given that so-called delayed adulthood is not unique to modern life, to make sense of it, we must look at the circumstances young adults find themselves in. Finishing school and finding a job can be seen as prerequisites for the main factors—becoming financially stable and independent—that impact someone's ability to reach the other milestones of adulthood. Young adults’ ability to find a job that enables them to be financially independent affects their ability to leave home, and feel comfortable marrying and raising children. A Pew Research Center study found that lack of financial readiness is a key reason for delaying marriage among young adults today.

The time it takes to transition to adulthood has more to do with being able to transition to the workforce than the perceived apathy of youth. Young people reach adult milestones later when jobs that lead to financial independence are scarce or require additional training. The well-paying manufacturing jobs that were abundant in the 1950s did not exist in the 1890s. In the early 1900s, the U.S. transitioned from a largely agrarian economy to an industrialized one, and many young adults moved from rural to urban areas in search of modern industrial jobs.

In the context of this economic transition, the “high school movement” emerged. From about 1910 to 1940, there was a significant investment in high-school education, and enrollment rates increased from roughly 18 percent to 73 percent in that time. High-school curricula were designed to prepare students with the skills and knowledge they needed to succeed in the “new economy” of the 1940s, thereby aligning education with needed job skills. Better education meant that youth were better prepared for the jobs that flourished in the postwar economic boom, which meant that young people could transition to adulthood at earlier ages in the ’50s than they had been able to before. Stable jobs that required only a high-school education became scarcer in the subsequent decades, and achieving these milestones began to take longer.

Today, the economy is in transition again, which is affecting young adults’ ability to achieve the markers of adulthood. The rise of a knowledge-based economy means that this generation needs more education and training to gain the skills they need to succeed financially. Many entry-level jobs now require a college degree, which takes time to obtain. Achieving financial stability with only a high-school education is harder today than it was in the 1950s.

Trends in delaying adulthood play out across the decades and lead people to stereotype entire generations. However, within generations, there is also variation in who has the privilege to delay adulthood and who does not. All young adults are affected to some degree by the state of the economy they inherit. However, those who attend college get the luxury of more time to “figure things out” and to gain the knowledge and social capital that help them invent themselves in ways that align with the economy. Many of those who do not attend college take on the responsibilities of adulthood at an earlier age, regardless of their generation. Data show that they have a median age of first marriage that is two to three years younger than their peers who earn a college degree. Even those who graduated from college in the 1950s, the heyday of “early adulthood,” delayed marriage until a median age of 24 for women and 26 for men.

Young adults are not less mature today than in the past. Neither are they necessarily more self-centered. A new developmental stage is not necessary to account for the extended time that many youth need to make the transition to adulthood. We are not the first researchers to challenge the idea of “emerging adulthood” as a distinct life stage, but we have new historical data that help us understand when and why youth feel they need more time to become adults. Our findings tell us something important: When young adults take longer to achieve the markers of adulthood, it is not that something has changed about them; it is that the world has changed.