Smart Men Acting Stupid

In attempting to succeed in the Trump-era Republican Party, some politicians are masquerading as what they imagine voters want, with results that ring almost comically false.

In 2013, Bobby Jindal, then the governor of Louisiana and a presidential hopeful, delivered some tough love to the Republican National Committee: “We must stop being the stupid party.” Specifically, he continued, “we must stop insulting the intelligence of voters. We need to trust the smarts of the American people. We have to stop dumbing down our ideas and stop reducing everything to mindless slogans and taglines for 30-second ads.”

Even in the pre-Trump GOP, this was a bracing message, but Jindal was the person to make it: Known for his wonkish mien, Jindal had graduated from Brown at 20, scored a Rhodes Scholarship, become the youngest president of the University of Louisiana system, and then won the governorship.

Jindal’s speech is unthinkable today, not only because the Republican Party has moved in an even more decisively anti-intellectual direction, but also because the kinds of politicians who resemble Jindal—brainy, ambitious ones with Ivy League résumés—are pursuing the opposite course of action. This is the age of smart politicians pretending to be stupid.

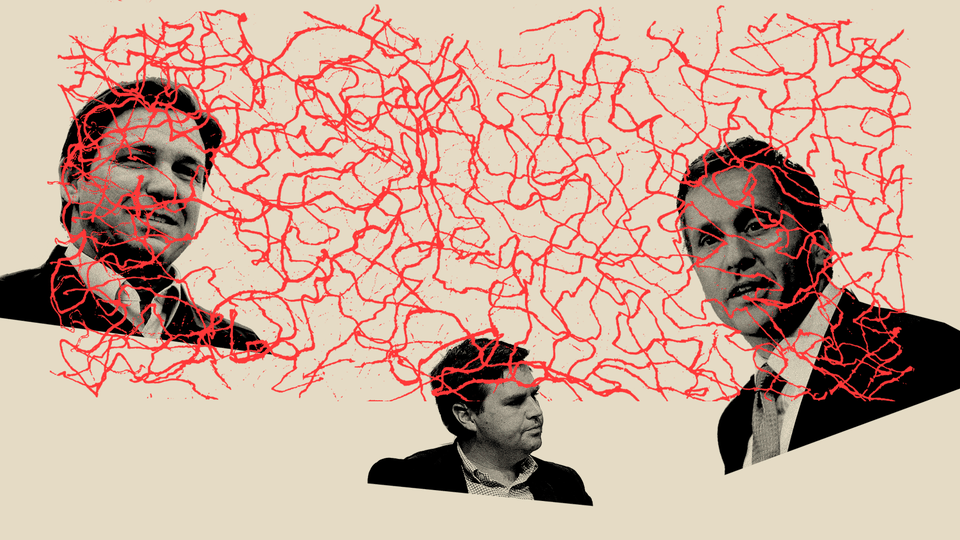

The prime offenders include Florida Governor Ron DeSantis (Yale College, magna cum laude; Harvard Law, cum laude), U.S. Senate hopeful Eric Greitens of Missouri (Duke, full scholarship; Rhodes Scholar), and U.S. Senate candidate J. D. Vance of Ohio (Ohio State, summa cum laude; Yale Law). Of course attending fancy schools does not necessarily make someone smart, nor do the well educated have a monopoly on intelligence. Smart people make bad calls all the time, moreover, as David Halberstam indelibly noted, and stupid ones stumble into good decisions. What these politicians have in common is that though they’ve given every indication they’re smart in the past, now—in their best attempt to succeed in the Trump-era Republican Party—they are masquerading as what they imagine voters want, with results that ring almost comically false.

Start with DeSantis. Last April, when vaccines were new and not nearly so politically polarized, the governor got the Johnson & Johnson shot, reportedly because he preferred a single shot to two. He didn’t get jabbed in public (“I’m not sure we’re going to do it on camera; we’ll see,” he told reporters. “If you guys want a gun show, maybe we can do it, but probably better off not”) but he did disclose that he’d gotten it, and then criticized the FDA for pausing distribution of J&J later that month.

Now, however, DeSantis won’t even say whether he’s received a booster shot. “So that’s something that I think people should make their own decisions on,” he said last week. “I’m not gonna let that be a weapon for people to be able to use. I think it’s a private matter.”

What’s going on here? One possibility is that since getting his first shot, DeSantis has become fervently, genuinely anti-vaccine, which would be pretty silly, because evidence is only mounting that the vaccines are both effective and safe. A second is that he has no personal objection to the vaccine but has decided to forgo the booster nonetheless, because he understands the anti-vax mood in the noisiest parts of the Republican base, and he wants to claim that mantle. The more likely scenario is the one that the conservative journalist Jonathan V. Last lays out: “You’re not supposed to remember this, but DeSantis is a smarty-pants, Ivy League elite lawyer who is playacting as a populist crusader … DeSantis almost certainly got the booster.” In short, he wants to claim the anti-vax mantle without foolishly endangering himself.

DeSantis is apparently going through these contortions because he is positioning himself for a 2024 presidential run—which would put him in conflict with former President Donald Trump, who sees the GOP nomination as rightfully his own. Trump, who has taken a pro-vaccine stance (the shots were mostly developed under his administration), quickly fired a shot across DeSantis’s bow. “I watched a couple politicians be interviewed, and one of the questions was ‘Did you get a booster?’” he said. “Because they had the vaccine and they’re answering like—in other words, the answer is ‘yes,’ but they don’t want to say it, because they’re gutless.”

This is a classic Trump attack: petty, entertaining, and authentic. Vaccines are one of the few issues on which Trump and his base have serious differences, and Trump has stuck to his stance despite backlash. But most of the time, Trump and his supporters are in lockstep. He doesn’t have to cater to voters, because his voters like both what he says and the way he says it—those are, in a sense, one and the same. As Jindal himself wrote in 2018, “Mr. Trump’s style is part of his substance. His most loyal supporters back him because of, not despite, his brash behavior.”

And though Trump is incorrigibly dishonest, he doesn’t have to pretend to be something other than what he is to win over voters. When Trump said in 2016, “I love the poorly educated,” he was perhaps overly blunt, but he wasn’t fibbing. The imitators, however, do not have his common touch, so instead they try to ape it. Their pantomime comes across as condescending. If they had come sincerely to the positions they’ve taken, they would be wrong, but because they seem disingenuous, they are also pathetic.

The other prominent offenders are not rivals to Trump but those seeking his affection. When J. D. Vance became nationally famous, it was as the brainy and accomplished author of Hillbilly Elegy, an up-by-the-bootstraps critique of rural white America that was decidedly conservative, analytical, and thoughtful. His résumé—not just the Ivy League, but the Marine Corps and stints in a white-shoe law firm and venture capital—made him seem like the opposite of Donald Trump. And indeed, when Trump came to prominence, Vance was among his harshest conservative critics.

These days, as a candidate for an open Senate seat, Vance has moved closer to Trump’s politics and is more likely to blame rural decay on China and free trade than on the decline of family values and hard work. That’s a valid ideological shift, and it may even be sincere: Many people have rethought their politics over the past half decade. But in his haste to run away from his past critiques of Trump, Vance has become a knee-jerk caricature of the kind of know-nothing bumpkin he once skewered.

“I sort of got Trump’s issues from the beginning,” Vance told Time last year. “I just thought that this guy was not serious and was not going to be able to really make progress on the issues I cared about.” So Vance has set out to make himself equally unserious. (Vance can be surprisingly unguarded about what he’s doing: “If I actually care about these people and the things I say I care about, I need to just suck it up and support him,” he added.)

He drew heavy criticism in October, when, after the actor Alec Baldwin accidentally shot and killed a cinematographer on a film set, Vance tweeted to then–Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey, “Dear @jack let Trump back on. We need Alec Baldwin tweets.” He referred to LeBron James, perhaps the greatest living Ohioan, as “one of the most vile public figures in our country.” He gives mealy half answers about anthropogenic climate change. He refuses to reject Trumpian stolen-election claims and offers red herrings about donors who stepped up when states wouldn’t fund boards of elections to adapt to the pandemic. On Tuesday, after nabbing an endorsement from Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia and infamy, Vance tweeted, “Honored to have Marjorie’s endorsement. We’re going to win this thing and take the country back from the scumbags.” (Vance’s leading GOP rival, Cleveland-raised Josh Mandel, delivers plenty of cringe himself, including adopting the worst faux-southern drawl since Hillary Clinton left the trail.)

Vance has a kindred spirit in Missouri, where Eric Greitens is seeking a political comeback after being forced to resign in a bizarre scandal in which (among other violations) he allegedly blackmailed a woman with whom he was having an affair. Like Vance, Greitens built his appeal on his impressive background. In addition to his formal education, he’d been awarded a Purple Heart in the Navy, written several books, and served as a White House fellow. For most of his life, he was a Democrat, before switching parties just ahead of running in Missouri. Admirers likened him to a Boy Scout, and even his critics agreed he was very smart. He gave talks with titles such as “The Culture of Character: Building Strength Through Study and Service.”

It’s hard to maintain that image when you’ve resigned in a sordid sex scandal, so Greitens is now campaigning as a Trump acolyte. He’s become a regular on Steve Bannon’s podcast, pals around with Rudy Giuliani and Michael Flynn, endorsed the sham Arizona election “audit,” and claims to subscribe to other debunked theories about the 2020 election. In a March 2021 interview with Hugh Hewitt, who was skeptical of his Senate candidacy, Greitens repeated the same flimsy phrases over and over, coming off as a Missouri Miliband.

To see a different vision of how an academically inclined Republican tries to make a way in the post-Trump party, look to Greitens’s fellow Missourian Senator Josh Hawley (Stanford; Yale Law; Supreme Court clerkship under John Roberts). Hawley doesn’t lack for cynicism, as his embrace of Trump’s effort to overturn the 2020 election demonstrated. Some of his former mentors are appalled by his actions. But Hawley has tried to use his intellectual reputation to forge a sort of thinking man’s Trumpism. That’s almost certainly a contradiction in terms, but the attempt at least fits his personality.

Contrast that with Vance. Last week, in an interview with Spectrum News, he dismissed concerns about his coarse remarks, including the Alec Baldwin tweet.

“Unfortunately, our country’s kind of a joke, and we should be able to tell jokes about it,” he said. “I think it’s important for our politicians to have a sense of humor. I think it's important for us to be real people.”

Ohioans have to choose whether this is the sort of attitude they want in a U.S. senator. As for Vance, he has to choose whether he wants to be a real person—or a joke.