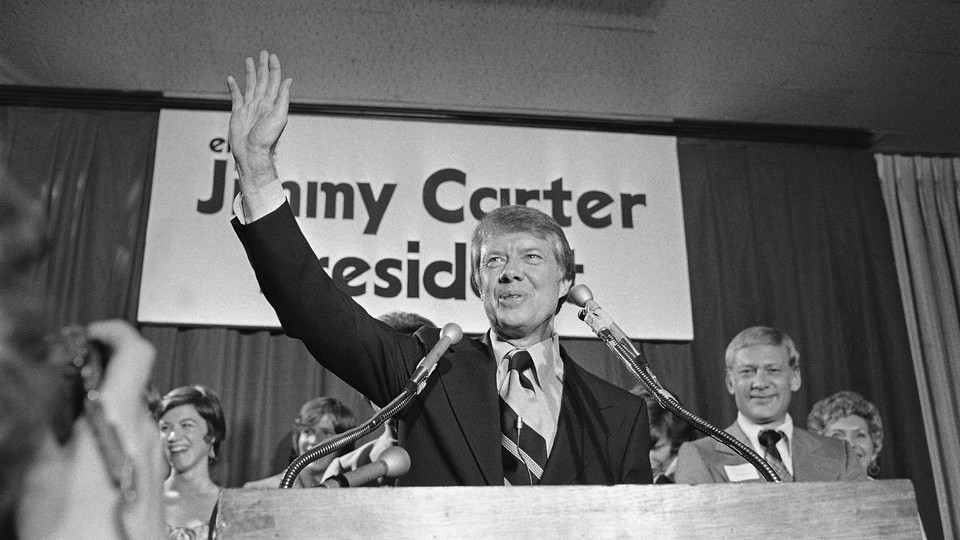

How Jimmy Carter Revolutionized the Iowa Caucuses

In 1976, he took on the Hawkeye State like no one had before, setting the precedent for hopefuls running in the race today.

There is a long history of surprise candidates doing well in the Iowa caucuses and defeating the “inevitable” nominees. And this year is no exception. Whether it’s Donald Trump or Ted Cruz, or if it’s Bernie Sanders or Hillary Clinton, next week, Iowans will get to have the first say.

How did this all start? How did the Iowa caucus—a strange election-year event where a small number of Iowans gather in homes, schools, and other civic buildings to announce their support for their candidates—become such a major political touchstone? With a mere 52 delegates, Iowa has nevertheless become a force in presidential campaigns over the last four decades. The caucus, which started in the 1840s, had traditionally fallen in the middle of campaign season. But in 1972, state reforms modernized the process and moved the date from May 20 to January 24, making it the first contest in the election. That’s when a campaign worker named Gary Hart convinced Democrat George McGovern to take the state seriously.

But where McGovern took Iowa seriously, it was Jimmy Carter who revolutionized the role that the Hawkeye State would play in presidential politics. Carter turned the Iowa caucus into a major event in 1976 and thereby demonstrated how an upstart campaign could turn a victory in this small state into a stepping-stone for gaining national prominence. When people talk about Carter’s legacy by focusing on his failed presidency or his transformative post-presidency, they forget one of his most lasting actions—his 1976 campaign, which all started in small, rural Iowa.

In late 1975, almost no one thought that Jimmy Carter, the former governor of Georgia, could ever be the Democratic nominee. There were already 11 Democrats running for office and some other prominent figures waiting to announce. Most of them were senators, like Henry “Scoop” Jackson and Birch Bayh, with national name recognition. When Carter announced that he was going to run, even his hometown newspaper, The Atlanta Constitution (now The Atlanta Journal-Constitution), joked in a headline: “Jimmy Who?”

But what Carter and his advisers understood from day one was that the old rules of campaigning no longer applied. The power of the party bosses, who used to decide on the candidate during the convention, had been destroyed as a result of reforms that were pushed by McGovern after the disastrous 1968 convention. Now, voters in each party held the balance of power through their pick at the primaries and caucuses. There was also more money available for non-establishment candidates. As a result of the Watergate campaign-finance reforms, any candidate could qualify for public financing as long as they raised at least $5,000 from private donors in a minimum of 20 states. Carter had worked hard to make this happen, selling T-shirts and peanuts while organizing rock concerts with bands like the Allman Brothers to encourage small donations to his candidacy. Most important, Carter was a relentless campaigner. After announcing his candidacy on December 12, 1974, Carter campaigned for 260 days in 40 states and 250 cities—all before any votes were taken.

From the start, the key to his strategy revolved around Iowa. Carter believed that if he could influence media coverage of his candidacy through a victory in Iowa, he would be treated as a serious candidate, making it easier for voters in subsequent contests, like New Hampshire, to vote for him. The actual delegate count from Iowa was less important than the kind of media coverage his victory would produce. He hired one of the best organizers in the business, Tim Kraft, to direct the organizational effort in the state. A skilled political hand, Kraft organized about 20 statewide committees, and each one was charged with finding volunteers for the caucus who would talk to neighbors about Carter’s candidacy and make certain that people showed up on voting day.

Carter and his team spent a considerable amount of time in Iowa as almost all of the other major candidates literally ignored the state. He went door to door, leaving notes at homes where nobody answered. His staff followed up with personalized thank-you notes to everyone he met. While the other candidates were looking at New Hampshire, Carter was focused on the voting that would take place a few days earlier. He spent an immense amount of time speaking with reporters from the local press and promoting the image of himself as a candidate from outside the Washington establishment who was not tied to the system that had created Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon. Reporters were attracted to his folksy mannerisms and the underdog story of a peanut farmer who was now running for the most powerful position in the world. “The people of this country,” Carter liked to say, “want a fresh face, not one associated with a long series of mistakes made at the White House and on Capitol Hill.”

During one early morning interview on a local television station, Carter embraced the politics of personality when he dressed up in an apron and chef hat to show to audiences how he liked to cook fillets of fish. He talked about the way he would slice the fish and how he liked to marinate them overnight. The appearance was a smash hit. He dazzled Iowan reporters with his in-depth knowledge of agricultural techniques. According to Carter’s memoirs, his wife, Rosalynn, would drive around various communities and tell television reporters and radio disc jockeys that her husband was running for president and then encouraged them to invite him on as a guest.

The national press caught on. New York Times columnist R.W. Apple Jr. published a story on October 27, 1975, in which he said that Carter “appears to have taken a surprising but solid lead in the contest for Iowa’s 47 delegates to the Democratic National Convention.” Apple had interviewed approximately 50 Iowans over a five-day period before reaching this conclusion. He also read a poll in The Des Moines Register that found Carter was gaining steam.

The New York Times story opened the floodgates. The media fell in love with the smart and scrappy Georgian, whose personality seemed to be the antithesis of the imperial presidency. Newsweek and People published features about him, and he received coverage on national TV shows. On Thanksgiving weekend, Carter appeared on CBS’s Face the Nation for the first time—after the producers had previously denied him an appearance for months.

Carter was brilliant at understanding that local political events could become a form of theater, staged for the benefit of the media. This was the case with the Jefferson Jackson Day dinner in December 1975. The annual fund-raiser was the traditional launch for every election year, and Kraft believed that the event needed to be treated as seriously as an election. He found volunteers who could transport Carter supporters to the dinner, and he arranged for supporters to have spectator seats in the balcony for just $2 a ticket. They got “everything but the chicken dinner,” one aide explained. On the night of the dinner, Rosalynn Carter walked up into the balcony with volunteers and handed out campaign pins to everyone in the front row. When the television cameras panned to the balcony, they would see all the Carter supporters. “Politics is theater,” Kraft said, “We planned for that.”

After the dinner, Carter saw his poll numbers skyrocket. Norma Matthews, the director of Representative Morris Udall’s campaign in Iowa, said that Iowa was “absolutely a media event” in the competition for front-runner status. Udall and others scrambled to catch up to Carter, but they were too late.

Meanwhile, the press couldn’t stop writing about Carter. Richard Reeves, the editor of New York Magazine, told the Times that the reporters all needed something to write about and, in January, “it’s Carter.” Almost 150 reporters converged on each voting precinct, and the three TV networks had reporters stationed in Iowa to cover the events, all despite the low delegate count.

On January 19, Carter defeated Birch Bayh by a two-to-one margin. Morris Udall, Scoop Jackson, Fred Harris, and Sargent Shriver didn’t come anywhere close. Though the largest number of votes were uncommitted, Carter came in second. “My husband and I wanted a fresh face and a new approach,” one Iowan explained.

Understanding that even the victory needed to be carefully choreographed, Carter flew to New York the night of the caucus so that he could stop by the networks the following day. The next morning, he appeared on NBC, CBS, and ABC to discuss his victory in person. The media acted exactly as he had expected, giving him airtime and treating him as a major candidate. The rest was history. Carter went on to win in New Hampshire and eventually took the nomination.

The Carter campaign of 1976 in Iowa seems quaint decades later. Candidates now have massive media operations that dwarf anything Carter could have imagined. The press itself, online and on cable, has a presence all over the country on a 24-hour news cycle that the old networks and city papers could never replicate. But the dynamics that Carter capitalized on as U.S. politics underwent a transformation in the early 1970s—and the way he handled the ensuing opportunities—remain at the heart of modern campaigns.

The good news is that old party bosses don’t rule the roost and candidates must appeal to average voters to win. There are no more smoke-filled rooms with elites trying to save the establishment candidate. The bad news, of course, is that the media has taken on a life of its own, with an ability to shape and determine who is up and who is down. And every candidate now feels forced to pander to the worst elements of reporters thirsty for a horse race with lots of drama.

The kind of politics that worked for Carter in 1976 now has an impact en masse throughout the country. Today, every candidate lives in the world that Carter helped to create that January in Iowa.