In an era when nothing can gain universal acclaim in Washington, the universal fanfare that has attended C-SPAN’s 40th anniversary on Tuesday is astonishing. “Happy birthday, C-SPAN. We need you more than ever,” writes The Washington Post’s Karen Tumulty. Her colleague Robert Costa calls it a “national treasure.” Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich says the nation owes C-SPAN “a big vote of gratitude for empowering citizenship in the television age,” while the liberal journalist Josh Marshall, who agrees with Gingrich on little else, says it “is one of the few, unmitigated pluses in the modern media world.”

Anytime so many people agree about something, there’s usually reason for suspicion. C-SPAN has much to recommend it, as these endorsements show. But like every silver cloud, it isn’t without a dark lining. Reporters and Congress-watchers love it for the convenience. Authors love it for the serious coverage of books. Cranky citizens love it for the opportunity to call in. But politicians love it for the chance to grandstand.

The standard joke about C-SPAN is that no one is watching. Back when comedians hosted the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, they practically had a contractual requirement to deliver some jab at the cable network. (I know this because C-SPAN cut together a compilation video of these jokes, which perhaps demonstrates it has a better sense of humor than the repetitive comics themselves. But I digress.) But what if the conventional wisdom about C-SPAN is wrong, and the problem is not that too few people are watching it, but too many? What if C-SPAN is not an anachronism, but an author of today’s political chaos?

Brian Lamb, who launched the channel and is now its executive chairman, rejects this idea. “When I first came to the town in 1966, I’d go up at night and sit up there and listen,” he told the Post recently. Members of Congress “performed on the floor of the House just like they do now.”

But C-SPAN can’t have its 40th-birthday cake and eat it, too. Either the channel was a revolution in the way Washington worked, in which case something has changed, or it wasn’t. Just take Gingrich, who arrived in Washington as a U.S. representative from Georgia the same year that C-SPAN debuted. As Frontline explained, he quickly grasped the power of the new outlet:

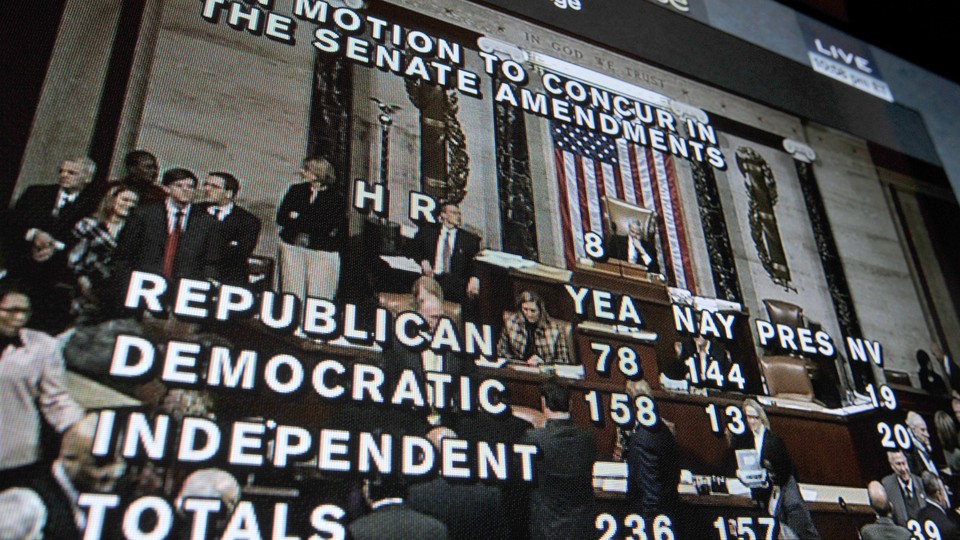

The House, which limits the length of debate over legislation, has a rule allowing so-called special orders—permission to give lengthy speeches at the end of each legislative day. These have long been a means by which congressmen could read into the Congressional Record various matters of importance to their constituents, usually matters of trivia. But Gingrich, concerned less with the Record than with the potential television audience, began to use special orders regularly as his platform for advancing ideas and, especially, for attacking the Democratic majority.

Often that meant that Gingrich and his rabble-rousing, rebellious allies were giving speeches to an empty House chamber. Once, in 1984, Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill, annoyed at Gingrich, had cameras pan to show that no one was listening to some stem-winder. (Gingrich himself would make camera pans a policy when, years later, he became speaker.) But O’Neill also lost his temper at Gingrich and snapped at him. His intemperate remarks were stricken from the record, the first time that had happened since 1798, and Gingrich’s prominence soared as a result. It didn’t matter that the House chamber was empty: Gingrich was able to get attention from the live coverage, or else from the blowups that he precipitated while speaking on the floor. The number of eyeballs on Gingrich at a given time didn’t necessarily matter, either. His behavior, like that of the politicians who would follow him, was affected by the mere potential for eyeballs.

That strategy might sound familiar after three years of watching Donald Trump—both the ability to speak to the public live on camera, without mediation, and also the knack for creating and exploiting crises. As my colleague McKay Coppins wrote last year, Gingrich pioneered Trump-style politics, though the current president’s rise depended even more on the new technologies of cable news and the internet—which was (not actually) invented by Al Gore, who was coincidentally the first speaker on C-SPAN in 1979, when he was a representative from Tennessee.

The aim to speak without any editorial intervention and create a ruckus is hardly the exclusive preserve of Gingrich or the president. Politicians from both parties have recognized Gingrich’s genius and embraced his technique. Using C-SPAN, Gingrich sought to sidestep what he viewed as liberal bias in the mainstream media, but circumventing the press’s mediation means that politicians can also offer complete hogwash directly to the public without anyone stopping falsehoods.

C-SPAN didn’t just create a way for politicians to vault out of the sleepy back benches of the House. It also changed the way things worked within the chamber. The most effective legislators are not always the most telegenic, and Congress’s work is sometimes unsavory. As Jonathan Rauch, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, has written in The Atlantic, well-meaning reforms have in fact weakened some parts of the American political system. That includes greater transparency for legislation, of which C-SPAN is a part. “Congress functioned better and people were happier with it when it was less exposed to public view,” he told me in a recent interview.

Meanwhile, the ability to speak live on TV to the nation makes politics less about achieving things directly and more about scoring points. As anyone who watched Michael Cohen’s testimony before the House Oversight Committee saw, many members are far more interested in speechifying than in asking substantive questions (much less listening to the answers). The political strategist and writer Yuval Levin has written about the idea of institutions as either formative or performative. “People trust political institutions because they are shaped to take seriously some obligation to the public interest as they pursue the work of self-government, and they shape the people who populate them to do the same,” Levin argues. “When the public doesn’t think of its institutions as formative but as performative—when the presidency and Congress are just stages for individual performance art … they become harder to trust.”

The outpouring for C-SPAN this week fits on both sides of Levin’s binary. The network does provide a useful service, though not one without complications and asterisks. Yet sincere praise for it is also a form of virtue-signaling that demonstrates that one is for transparency and fusty production values. Don’t criticize the people offering the praise, though: They’re just living in the world C-SPAN made.