Lost tribes the 1,000km rainforest mission to protect an Amazon village

Dom Phillips and Gary Calton joined an expedition to track the whereabouts of an uncontacted tribe, who threaten the safety of Brazil’s Marubo people

Dom Phillips and Gary Calton joined an expedition to track the whereabouts of an uncontacted tribe, who threaten the safety of Brazil’s Marubo people

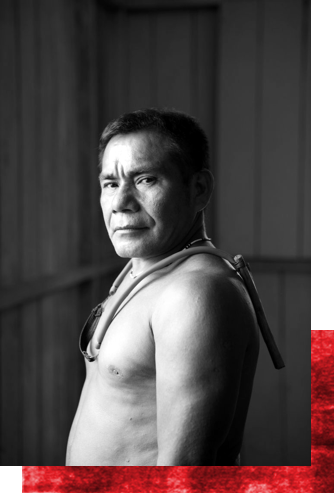

Wearing just shorts and flip-flop as he squats in the mud by a fire, Bruno Pereira, an official at Brazil’s government indigenous agency, cracks open the boiled skull of a monkey with a spoon and eats its brains for breakfast as he discusses policy. Pereira is an “indigenista”, a specialist in recently contacted and isolated indigenous people whose job for Funai, as the agency is known, includes monitoring these groups in the Javari Valley, a remote reserve the size of Austria. He also leads gruelling expeditions like this one – a 17-day journey by boat and on foot into thick Amazon jungle – which also demands a strong stomach. Pereira plays down the difficulties he and other indigenistas face in their work. But he admits a conservative government, influenced by an agribusiness lobby with its eyes on indigenous land, is depriving Funai of resources and making things harder. “It’s not about us,” says the burly, bespectacled 38-year-old. “The indigenous are the heroes.”

The Javari Valley reserve, which was set up in 1998, is home to 6,000 indigenous people from eight tribes, who share its dense, hilly forests and sinuous rivers with 16 isolated groups. Indigenous leaders say the “isolados”, as they are known, are more threatened than they have been in decades – with heavily polluting gold mining barges entering rivers to its east, cattle ranchers encroaching on its southern borders, and commercial fishing gangs venturing deep into its centre. Keeping tabs on their wellbeing is vital. Although since 1987, government policy has been to avoid contact with them, indigenistas like Pereira pore over reported sightings, satellite images, photos from planes used for monitoring. Expeditions like this one – which Guardian reporters were given rare permission to join following an invitation from the Javari Valley indigenous association, Univaja – provide invaluable intelligence. The nine-man team travelled around 950km by boat and hiked 70km to investigate reported sightings by Marubo villagers of isolated people near a tiny, remote hamlet called São Joaquim deep inside the reserve. In 2015 the village moved location, concerned by repeated visits from isolados.

Daniel Mayaruna carries a hunted wild boar; Iskasharoo Marubo, with her friend Sheta Marubo, Rio Novo village © Gary Calton

There are around a thousand Marubo in the Javari Valley. First contacted over a century ago, they are accomplished farmers, carpenters, hunters and fishermen. Regarded as the valley’s diplomats, they still use the high-ceilinged, thatched communal huts called malocas. When visits from isolados started at São Joaquim’s new location, villagers were spooked. “People are scared. We are not used to seeing them,” says Mônica Marubo, 23, São Joaquim’s village teacher. “I think they are scared too. They see us and they run.” Machetes, bananas and an axe have been stolen. When last August, a freshly killed cutia – a large forest rodent – was left, villagers surmised it was a present. In November, Josimar Marubo, 30, saw two naked, long-haired men with a bow and arrow taking bananas from his plantation. “They saw me and they ran off,” he says. Though interactions with the isolados have so far been peaceful, their unpredictable nature means the Marubo fear a violent attack. There has been bloody conflict between contacted and uncontacted groups elsewhere in the Javari Valley. Josimar joins the expedition – one of seven indigenous people donning green Funai shirts and forage hats. Indigenous people like him are the ninjas of this forest, and are as protective of it as they are at home in it. They fish piranhas and hunt, butcher and cook birds, monkeys, sloth and wild boar to eat. They slash trails through tangled undergrowth, and break camp – clearing ground, cutting down saplings to make wooden frames, stretching tarpaulins over them and hanging hammocks, often in torrential rain.

Expedition leader Bruno Pereira explains the route. © Gary Calton

Manoeuvring the aluminium boat up the Sapotá River to the set-off point requires slashing through creepers and undergrowth, cutting through thick fallen trees with axes. They even jump into the muddy waters to push the boat over a sunken log, unfazed by the alligators that infest them. And within 90 minutes of departing in single file the next morning, they find signs of the isolated people – plant stalks bent down at a 45-degree angle, called “quebradas”, left to mark the route. Pereira examines them closely, to confirm they weren’t broken by a branch falling from above or by a tapir leaving its teeth marks. “This is people,” he says. “One month [ago].” Alsino Marubo, 35, takes photos while Pereira marks GPS points. There are more bent branches nearby – some snapped with a machete, others by hand. Nobody else hunts here, which is confirmation that isolados have used this route. “This is strong information,” Pereira says. “We were lucky.” Five days of jungle hiking follow. The ground is soft and damp, like a compost heap, slick with sticky mud or knee-deep in brackish, swampy water. Steep, slithery inclines are climbed by grabbing trees and branches and avoiding those with long needles or sharp, spiky bumps. The men cut long, thin stabilising poles to help them balance over slippery logs lying across muddy rivers. They celebrate coming across an enormous, rare mahogany tree, spreading majestically over a spacious, sun-dappled stretch of jungle.

Whether foraging for fruits and nuts, or discerning by scent where wild boar or a jaguar have passed, the more recently contacted Korubo seem especially attuned to the landscape. “They walk in the forest more than us,” says Josimar, joined on this expedition by two Korubo men and two boys – Takvan, his adopted son Xikxuvo Vakwë, around 12, Lëyu and his son Seatvo, around 15. There are only around 80 Korubo, and they have a fearsome reputation. Known as the caceteiros – or “clubbers” – for the shoulder-height wooden batons they use for hunting and killing their enemies, they helped preserve the Javari Valley during the last century by beating off invaders, despite suffering much higher casualties themselves. The first isolated Korubo group was contacted in 1996. They killed a Funai employee a year later. Another isolated group killed two men from the Matis tribe in a land dispute in 2014. The Matis counter-attacked with shotguns, leaving nine Korubo dead and capturing dozens more. Funai stepped in and negotiated a tense contact process with no casualties. The Korubo wake before dawn, chattering incessantly, mocking each other and their expedition companions engagingly, imitating birds and monkey calls so convincingly that the animals reply. Then they eat everything they can – meat, guts, brains – and collapse asleep straight after their evening meal. When the cry of “snake!” goes up one afternoon, Takvan shoulders his club and goes off to deal with it. “Be careful!” cries Pereira, needlessly. Three loud thumps follow. Seatvo appears, beaming, dangling the metre-and-a-half venomous Jararaca snake on a stick.

Leyu Karubo after a haircut; Josimar Marubo with his wife, Leonilda (right), children Ivan Jnr and Jacinido, and sister-in-law Mônica Marubo with her son Mai, in São Joaquim. © Gary Calton

The indigenous members of the expedition – Marubo, Korubo and one Mayaruna, Daniel – are all thrilled to hunt, whether bringing down a sloth, shooting wild birds, or bagging four monkeys – Lëyu shimmies a hundred feet up a tree in seconds to bring one down. The Korubo singe off the monkeys’ fur on the fire and butcher them, boil their meat, and roast their innards – the stomach dripping with delicious fat that tastes of pancetta. One morning the Korubo boys beat a hive to chase away the bees, then share its rusty-red honeycomb, dribbling with sweet, wild honey. For them, this is not a forbidding jungle but a vast organic supermarket whose wares are hidden to the uninitiated. The Korubo still have isolated relatives living in the forest. Xikxuvo Vakwë was among a group contacted in 2014. He says his father had been poisoned by his own brother, covetous of his wife. The group was gripped by an epidemiological crisis. “There was not much food,” Xikxuvo says. “There was a lot of fever, headaches.” Contact with white people was good, Xikxuvo concludes, because they had medicines. Takvan adopted the boy and his mother Malu, who became his second wife. Xikxuvo and Seatvo play, tease, giggle and goad each other like teenage boys anywhere. But their toys are machetes and clubs, not cellphones and video games, and they carry dead sloth and monkeys on their backs, tied with strips of inner bark.

Takvan Korubo (left) and Daniel Mayaruna sharpen machetes; Sheta Marubo holds a turtle; Marcir Ferreira carries wooden trusses to support the hammocks. © Gary Calton

Neither Korubo nor Marubo use pesticides or fertilisers on the small plantations where they grow manioc, bananas, corn, melon and fruits like cupuaçu. Their minimal impact on the forest confirms reports such as a 2016 World Resources Institute study, which concluded that tenure-secure, indigenous forestlands have lower deforestation rates. Maintaining them is a cost-effective way for Brazil to mitigate climate change and meet its commitments under the Paris climate accord. But high-profile politicians on left and right argue that commercial agriculture and mining should be allowed in indigenous reserves. Alsino Marubo has an emphatic response for them. “No,” he says. “We take care of our land.” After five days, the expedition reaches the wide expanse of the Ituí River, its light and space a relief from the dense, claustrophobic forest. The expedition had found quebradas on the first two days. After regrouping and heading back up the River Sapotá, more are found during three further days spent exploring around its banks. Pereira concludes that the isolated group lives on distant higher ground near a riverhead, and uses the route to visit São Joaquim. This adds more pieces to the jigsaw puzzle helping create an understanding of this isolated group, and comes as an immense relief to Marubo villagers, who were worried they had moved close by. “They live far away,” says Josimar. “I was thinking of moving and leaving a space for them, but now I think I’ll stay.”

All video © Gary Calton

The Marubo village of Rio Novo; members of the Korubo tribe. © Gary Calton