Charles W. Herbster is a jet-setting businessman and Republican mega-donor with deep pockets. He’s also a cattle rancher and born-again Christian who draws on farming metaphors with ease.

He’s fashioning a public image around those identities in his campaign for governor of Nebraska. But the most defining feature of his candidacy has been loyalty, similarities and ties to Donald Trump.

The former president endorsed Herbster last year, a potential game-changer in a state where Trump got 75% of votes in heavily GOP western Nebraska in 2020 and 58% statewide.

Gubernatorial candidate Charles W. Herbster, center, greets Esther Sousa, left, and Virgil Patlan during a campaign event at VFW Post 2503 in Omaha on Feb. 24. Herbster briefly ran for governor in 2014 but shelved his campaign after his wife became ill.

But, unlike his top primary competitors, Herbster has never held public office. His history and lack of policy expertise hold potential pitfalls.

He’s come first in recent polling, followed by Jim Pillen, a Columbus hog producer and University of Nebraska regent, and State Sen. Brett Lindstrom of Omaha.

This isn’t Herbster’s first go at the office: He launched a run in 2014 but quickly pulled out when his wife became ill. He then made headlines for donating historically significant sums to another candidate, Beau McCoy. As of January, Herbster had almost entirely self-funded his current campaign, to the tune of $4.7 million.

People are also reading…

Will Herbster’s front-runner status last?

Small-town roots, big-time businessman

Herbster, 67, was born in Falls City, a town of about 4,000 tucked into Nebraska’s southeastern corner. He went to Falls City High School, where he was involved in myriad organizations and spoke at his graduation ceremony, then the University of Nebraska-Lincoln for a couple of stints in the ‘70s. He did not attain a degree.

It seems he hasn’t slowed down since.

Nebraska gubernatorial candidate Charles W. Herbster speaks during a debate hosted by Nebraska Public Media in Lincoln on Thursday. Herbster is viewed as a front-runner in the Republican race for governor.

The man heads several businesses across five states. He got a job with Conklin Company Inc. in the 1970s and rose through the ranks. He and his late wife, Judy, who also worked at Conklin, ultimately bought it in the early ’90s.

Conklin manufactures over 130 products, including roofing and agriculture products. Distribution is based in Minnesota, and they moved administrative offices to Kansas City, Missouri, in the 2000s.

Basing the company out of state has sparked criticism from those opposed to his run for governor, including Gov. Pete Ricketts, who has endorsed Pillen and said he doesn’t believe Herbster is qualified to be governor.

“I was just going to do what’s economically the best for our people,” Herbster said of moving the offices to Missouri.

Herbster also heads Carico Farms and Herbster Angus Farms in Falls City, a bull semen operation in Virginia and Kansas City-based Judy’s Dream, which distributes nutritional shakes and supplements. He’s active nationally in the evangelical community and said he’s sponsored the National Day of Prayer for over two decades.

The land on which Carico and Herbster Angus Farms sit has been in Herbster’s family since the 1800s, he said. Herbster Angus Farms was incorporated in 2015, and Carico Farms was incorporated in 1981 — Secretary of State’s Office records show that document was signed by Herbster and his grandmother.

His grandmother, whom he named as one of his top influences, owned the farm, and he said his parents worked at the local hospital and bank.

Now, Herbster owns homes in Falls City, farmland in Colorado, a condo in downtown Omaha and a home in Kansas City, which he said he’s stayed in just a few times since Judy’s death in 2017.

Given his scattered portfolio, Herbster has faced criticism for weak Nebraska ties. At a recent campaign event, he addressed those criticisms by citing his time spent living in Grand Island, then Lincoln.

But, in an interview, Herbster said he’s spent most of his time since 1992 “on an airplane.”

Charles W. Herbster applauds during a speech by Kellyanne Conway, an adviser to Donald Trump, at an event in Omaha on Feb. 24. The former president has endorsed Herbster in the Republican race for Nebraska governor.

“We live in hotels, and we live on an airplane,” he said. “Because, without children, it’s very easy for us to just stay out there and continue to work with our people. That’s how we built the business.”

He said he still spends summers on the farm in Falls City. According to the Richardson County Clerk’s Office, Herbster has been registered to vote there since 2004. He was registered in Lancaster County before that.

Asked if he’d step away from his businesses if he wins the race, Herbster didn’t offer a clear answer: “If I become the governor of the state of Nebraska, my number one focus will be on making Nebraska great again,” he said.

Touting Trump ties

Trump endorsed Herbster despite Ricketts’ attempt to dissuade him from doing so, according to Politico’s reporting. South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem is among his other backers.

At campaign events, Herbster often sounds like Trump, pumping up his credentials as a political outsider and successful businessman, name-dropping, and focusing on national wedge issues like securing the country’s southern border.

“I’m very concerned about the direction of America,” he told The World-Herald. “And as America goes, so goes every state.”

Herbster often opens public appearances by extending greetings from the former president. Multiple people affiliated with his campaign, including Kellyanne Conway, have worked for Trump. The Herbster campaign cut ties with longtime Trump aide Corey Lewandowski last year, after a woman accused him of sexual harassment.

Herbster donated $1.3 million, in all, to Trump’s 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns. He was there when Trump announced his candidacy in 2015 and later led the Agriculture and Rural Advisory Committee for his campaign and administration.

When he announced his campaign, he put his loyalty to Trump above his run for office: “Everybody said: ‘You’re going to run for governor? You have to take the Trump (license) plates off,'” he said. “And this is how loyal I am to the 45th president of the United States, I said: ‘If it’s the difference between being disloyal to President Trump or becoming governor of Nebraska, I will not be disloyal to the 45th president.’”

Herbster was at a meeting Jan. 5, 2021, in Trump’s private residence in his Washington, D.C., hotel, where they discussed how to pressure more members of Congress to object to the Electoral College results affirming Joe Biden’s victory. And he was there the next day at Trump’s rally before the violent attack on the nation’s Capitol. He now downplays his participation and says he never heard that anybody was going to the Capitol to do anything.

And, despite previous statements and records showing he bought into baseless claims that the election was stolen, he now accepts that Biden is president.

Talking to reporters after a recent debate, though, he again expressed doubts about the integrity of the 2020 election. And he asserted without evidence that China released the COVID-19 pandemic to oust Trump from office and divide the country.

On state policy, a dearth of specifics

Herbster is an energetic speaker and can capture a crowd’s attention. But when it comes to Nebraska-specific policy, he rarely offers detail.

At a recent campaign event, he handed the mic to a staffer when it came time to talk about his campaign’s idea for caring for veterans in the state. He has pledged that there’ll be “zero critical race theory” in Nebraska — but admitted he doesn’t know how he’d accomplish that.

He says he’d crack down on illegal immigration and drugs and “close the border in Nebraska.” When asked what he meant by that, Herbster suggested he’d meet incoming groups of undocumented immigrants “wherever they park.”

Charles W. Herbster greets people during a campaign event at VFW Post 2503 on Feb. 24. Herbster has never served in elected office. The Republican candidate for governor is running on his business experience.

In an interview, Herbster spoke enthusiastically about requiring identification to vote and another specific proposal: branding and marketing the state. He pictures a state silhouette stamped on every box and wrapper that leaves the state, in red alongside words akin to “Made in Nebraska.”

“Everywhere I go in the state, and I’ve been traveling constantly, everybody’s going to talk to you about property tax,” he said. “We’ve been talking about that in Nebraska for 15 years. Everybody knows that, and we will address it, I will address it. But to me, it’s bigger than that. It’s a vision of how do we brand and market our state.”

On Nebraska’s tax code, his campaign website said that he’d advocate for shifting to a consumption tax-based system. But, in conversation, he didn’t commit to one approach.

He has said the tax code is outdated and that any solution needs to be “revenue neutral,” meaning the state won’t end up collecting more taxes. He named a few proposals for reforming the tax code from which he could draw, including a consumption tax-based proposal and a statewide initiative from Nebraska business and higher education leaders called Blueprint Nebraska.

Herbster said that one of the ways he manages to run several businesses is through hiring good people and delegating, and that he’d do the same as governor.

If he wins the primary on May 10, he said he’s going to immediately start assembling teams of people to work on branding, marketing, taxes, workforce and mental health issues facing veterans and law enforcement officers.

“I can assure you that every single person, even if they did not vote for me — I’m not concerned about what their political affiliation is: Republican, Democrat, independent or none of the three — every person will have a seat at the table,” he said.

Herbster’s former running mate, former State Sen. Theresa Thibodeau, called the campaign “chaotic and disorganized.” She has since launched her own campaign for the Republican nomination.

“He just wasn’t getting a good grasp on Nebraska policy and not going into that,” she said. “And I would say that, as I’m on the campaign trail, I continue to see exactly the same thing: That there’s really no depth to, you know, learning Nebraska issues.”

Divisive among locals

On a recent visit to his southeastern Nebraska hometown, The World-Herald found there was about an equal chance of running into Herbster supporters and detractors.

Joe Kuttler, a fellow farmer north of town, said he’d “recommend him for the job, above all the rest.” Herbster got a good start, he said, but took care of what he inherited.

Heidi Billingsly, who worked as Judy Herbster’s assistant for a few years before her death, called Herbster “a great person” who takes care of his employees and loves the state of Nebraska. If people have a negative perception of him, she said, it’s probably because they don’t know him.

Gubernatorial candidate Charles W. Herbster speaks during a meet and greet event at VFW Post 2503 in Omaha on Feb. 24.

A couple of people in town mentioned issues they have with Herbster, but didn’t want to speak for this story.

But Kim Griffiths of Verdon, just north of Falls City, offered a story about Herbster from decades ago, when he hired her family’s hay-baling business. When they arrived, they found the hay wasn’t ready but Herbster insisted they bale it anyway, she said.

So they did, but they never got paid. When the hay predictably rotted, she said Herbster called angry, demanding they help him remove the hay from his barn. They did it to avoid drama, she said, and swallowed the loss.

The way she sees it, he uses other people to get ahead with no regard for what happens to them.

“Herbster will never have our family’s vote. … He’s going for a glory ride on Donald Trump’s coattails,” she said.

Herbster’s campaign did not offer a response to Griffiths’ recounting.

Late taxes and a lead foot

Herbster has blemishes in his record, including a history of paying property taxes late and accumulating traffic violations.

In 2014, The World-Herald reported that he had almost always been late on his taxes in Richardson County in the previous two decades and sometimes waited a year or more to make a payment. A KMTV investigation last year found that Herbster and his businesses had paid late nearly 600 times. Herbster told KMTV that it was a choice, meant to offset cash flow issues.

But he’s faced criticism for his reasoning. Specifically, Ricketts and others point to 2014, when Herbster was late but also donated $2 million to McCoy, the then-gubernatorial candidate.

Herbster also acknowledged back in 2014 that he has a long list of driving offenses and that his license was temporarily suspended in 2002. At the time, he had been fined 21 times in Missouri and Nebraska in the previous 14 years.

Last year, he told the Falls City Journal that he likely had 34 speeding tickets in 35 years and called that one-ticket-a-year rate “not bad.”

Violations visible in public records include speeding tickets, charges for making unnecessary noise and other offenses. The most recent that’s publicly available in Missouri was in 2018, when Herbster pleaded guilty to an amended charge of failure to register and paid a fine.

Herbster acknowledged that the property taxes and traffic violations might be red flags for voters. But he ultimately paid all his taxes, he said, and paid interest and penalties — which he framed as a positive result for Richardson County.

Charles W. Herbster speaks at an event at VFW Post 2503 in Omaha on Feb. 24. Several polls indicate Herbster, a Falls City businessman who regularly touts his ties to former President Donald Trump, is the front-runner in the Republican race for governor.

THE WORLD-HERALD

“The only person I really hurt by being almost bankrupt is me,” he said. “And, if you are not running for political office, it would mean nothing to anybody, because politicians have been coming to me for 20 years wanting money. They were concerned very little about my taxes or my speeding tickets.”

How powerful is the Trump endorsement?

What’s yet to be seen is if Herbster’s self-branding as the Trump-endorsed candidate will pay off. Asked what he thought of Ricketts’ request to Trump, Herbster laughed and said, “It’s a free country.”

“I would’ve ran for governor irregardless of who or who wasn’t gonna endorse me,” he said.

While he loves having endorsements, he said, that doesn’t win a race.

“Races are won on candidates who have the vision, have a message and who work harder than anybody else,” he said.

At least one longtime political observer, though, sees Herbster’s candidacy as a referendum on that concept.

“Traditionally, you’d rather have an endorsement than not, but it wasn’t a deciding factor for most voters,” Lincoln-based political consultant and lobbyist Perre Neilan said. “Herbster flips that notion on its head and says the Trump endorsement is the ONLY thing that matters.”

Nebraska’s 10 most recent governors

Briefly: Ricketts, whose billionaire family owns the Chicago Cubs, has won two terms as governor. He has focused on taxes, regulations and government efficiency.

Briefly: Heineman became Nebraska’s longest-serving governor after moving up from lieutenant governor. A staunch conservative, he oversaw two major tax cut packages.

Briefly: Johanns put thousands of miles on his car campaigning for governor. A former Lincoln mayor, he went on to become U.S. Secretary of Agriculture and spent one term in the U.S. Senate.

Briefly: Nelson served two terms as governor and two in the U.S. Senate. As governor, he merged five state agencies and kept Nebraska from being the site of a low-level radioactive waste dump.

Briefly: Orr was Nebraska’s first woman elected governor. She oversaw the creation of business tax incentives and a push to increase university research. She has reemerged as a political force in recent years.

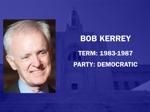

Briefly: Kerrey is a decorated Vietnam War veteran who led the state through a major farm crisis. He went on to serve two terms in the U.S. Senate. While governor, he dated actress Debra Winger.

Briefly: Thone, better known as “Charley,” spent eight years in Congress before being elected governor. He focused on education and economic development.

Briefly: Exon, a two-term governor and three-term U.S. senator, became the patriarch of the state Democratic Party. As governor, he was a fiscal conservative and an early proponent of ethanol.

Briefly: Tiemann, a reformer, took office in the midst of a state tax crisis. His solution — creating the state sales and income tax system — cost him a second term.

Briefly: Morrison, who served three 2-year terms as governor, was known as a tireless promoter of Nebraska. He pushed tourism and criminal justice reform.