After months of tests, troubleshooting and repairs, engineers began fueling the Space Launch System moon rocket for blastoff Monday on a long-overdue test flight to send an uncrewed Orion capsule on a 42-day voyage around the moon.

Rain showers with lightning moved within five nautical miles of launch pad 39B just after midnight, forcing Launch Director Charlie Blackwell-Thompson to delay the start of propellant loading by 55 minutes. But the six-hour procedure finally got underway at 1:13 a.m. EDT.

The only other issue under discussion as the countdown ticked into its final hours was troubleshooting to find the cause of a momentary communications glitch in one of the channels relaying commands and telemetry to and from the Orion spacecraft.

It was not immediately clear what impact, if any, the fueling delay and troubleshooting might have on the planned 8:33 a.m. launch time. But engineers were optimistic about getting NASA’s most powerful off on its long-awaited maiden flight at some point during a two-hour launch window.

The carefully scripted fueling procedure is required to load 196,000 gallons of liquid oxygen and 537,000 gallons of hydrogen into the rocket’s huge core stage. Another 22,000 gallons of oxygen and hydrogen are required for the upper stage, for a total of 750,000 gallons of propellant.

NASA

The SLS’s four shuttle-era engines and two extended strap-on solid fuel boosters will generate a ground-shaking 8.8 million pounds of thrust to propel the 5.7-million pound rocket away from pad 39B at the Kennedy Space Center.

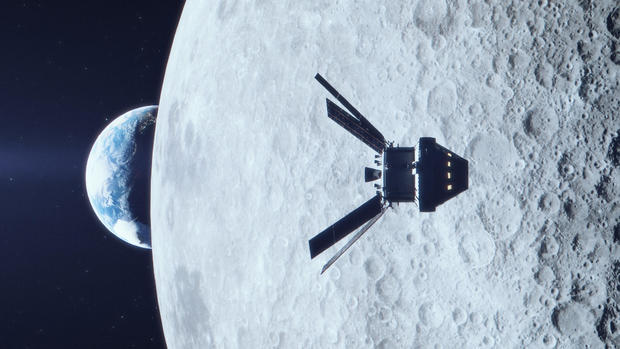

The rocket’s part of the Artemis 1 mission will last just an hour and 36 minutes, boosting the Orion capsule and its European Space Agency-supplied service module into space, out of Earth orbit and onto a trajectory toward the moon.

After a close flyby at an altitude of just 60 miles, Orion will whip back out into a distant orbit around the moon for two weeks of tests and checkout. If all goes well, the capsule will fall back toward the moon for another close flyby on October 3 that will set up a high-speed descent to a Pacific Ocean splashdown on October 10.

NASA

NASA plans to follow the Artemis 1 mission by launching four astronauts on a looping around-the-moon flight in 2024, setting the stage for the first astronaut landing in nearly 50 years when the first woman and the next man step onto the surface in the 2025-26 timeframe.

But first, NASA must prove the rocket and capsule will work as planned and that begins with Monday’s Artemis 1 launch.

Starting about 6.6 seconds before launch, the four RS-25 engines at the base of the core stage will ignite and throttle up to full thrust, generating a combined two million pounds of thrust.

When the countdown hits zero, after a lightning round of computer checks to verify engine performance, commands will be sent to ignite both solid rocket boosters. At the same instant, signals will detonate four explosive bolts at the base of each booster, freeing the SLS from its launch pad.

The solid rocket boosters provide the lion’s share of the power needed to lift the SLS out of the dense lower atmosphere, firing for two minutes and 10 seconds before falling away at an altitude of 27 miles.

The RS-25 core stage engines will continue the ascent on their own, firing for another six minutes to boost the rocket to an altitude of 87 miles.

The core stage’s RS-25 engines will fire for eight minutes, boosting the ship to an altitude of 87 miles before shutting down.

The flight plan called for the rocket’s upper stage, carrying the unpiloted Orion capsule and its European Space Agency-supplied service module, to separate from the now empty core stage and continue coasting skyward toward an altitude of about 1,100 miles, the high point, or apogee, of its initial orbit.

The engine powering the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, or ICPS, was expected to fire 51 minutes after liftoff to raise the low point, or perigee, of the orbit from 20 miles to about 115.

Reaching that low point forty-five minutes later — one hour and 36 minutes after launch — the ICPS was programmed to fire its RL10B engine for 18 minutes, boosting the vehicle’s velocity to about 22,600 mph, more than 10 times faster than a rifle bullet.

That’s what is required to break free of Earth’s gravity, raising the apogee to a point in space where the moon will be in five days.

NASA

After spreading its four solar wings and separating from the ICPS, the Orion capsule will head for a 60-mile-high flyby of the moon on September 3 and then into a “distant retrograde orbit” carrying the spacecraft farther from Earth — 280,000 miles — than any previous human-rated spacecraft.

The flight is the first in a series of missions intended to establish a sustained presence on and around the moon with a lunar space station called Gateway and periodic landings near the south pole where ice deposits may be reachable in cold, permanently shadowed craters.

Future astronauts may be able to “mine” that ice if it’s present and accessible, converting it into air, water and even rocket fuel to vastly reduce the cost of deep space exploration.

More generally, Artemis astronauts will carry out extended exploration and research to learn more about the moon’s origin and evolution and test the hardware and procedures that will be necessary before sending astronauts to Mars.

The goal of the Artemis 1 mission is to put the Orion spacecraft through its paces, testing its solar power, propulsion, navigation and life support systems before a return to Earth October 10 and a 25,000-mph plunge back into the atmosphere that will subject its protective heat shield to a hellish 5,000 degrees.

Testing the heat shield and confirming it can protect astronauts returning from deep space is the No. 1 priority of the Artemis 1 mission, an objective that requires the SLS rocket to first send the capsule to the moon.

If all goes well with the Artemis 1 mission, NASA plans to launch a second SLS rocket in late 2024 to boost four astronauts on a looping free return trajectory around the moon before sending landing the first woman and the next man on the moons surface near the south pole in the Artemis 3 mission.

That flight, targeted for launch in the 2025-26 timeframe, depends on the readiness of new spacesuits for NASA’s moonwalkers and a lander being built by SpaceX that’s based on the design of the company’s reusable Starship rocket.

NASA

SpaceX is working on the lander under a $2.9 billion contract with NASA, but the company has provided little in the way of details or updates and it’s not yet known when NASA and the California rocket builder will actually be ready for the Artemis 3 lunar landing mission.

But if the Artemis 1 test flight is successful, NASA can check off its requirement for a super-heavy-lift rocket to get the initial missions off the ground. With 8.8 million pounds of liftoff thrust — 15 percent more than the Saturn 5 — the SLS rocket is the most powerful ever built by NASA.

Congress ordered NASA to build the rocket in the wake of the space shuttle’s 2011 retirement, requiring the agency to use left-over shuttle components and existing technology where possible in a bid to keep costs down.

But management miscues and technical problems led to delays and billions in cost overruns. According to NASA’s Inspector General, the U.S. space agency “is projected to spend $93 billion on the Artemis (moon program) up to FY 2025.”

“We also project the current production and operations cost of a single SLS/Orion system at $4.1 billion per launch for Artemis 1 through 4, although the Agency’s ongoing initiatives aimed at increasing affordability seek to reduce that cost.”

Among the causes listed as contributing to the SLS’s astronomical price tag: the use of sole-source, cost-plus contracts “and the fact that except for the Orion capsule, its subsystems and the supporting launch facilities, all components are expendable and ‘single use’ unlike emerging commercial space flight systems.”

In stark contrast to SpaceX’s commitment to fully reusable rockets, everything but the Orion crew capsule is discarded after a single use. As SpaceX founder Musk likes to point out, that’s like flying a 747 jumbo jet from New York to Los Angeles and then throwing the airplane away.

“That is a concern,” Paul Martin, the NASA inspector general, said in an interview with CBS News. “This is an expendable, single-use system unlike some of the launch systems that are out there in the commercial side of the house, where there are multiple uses. This is a single-use system. And so the $4.1 billion per flight … concerns us enough that in our reports, we said we see that as unsustainable.”